Explore humanity’s first moon landing through newly discovered and restored archival footage. CNN Films “Apollo 11” premieres Sunday, June 23 at 9 p.m. ET/PT.

As you read this, a spindly-looking silver robot with a satellite dish for a head is exploring places never seen up close before by humans.

Named after the pet rabbit belonging to the mythical Chinese lunar goddess Chang’e, the Yutu 2 rover is making history as it sends back images and other data from the far side of the moon.

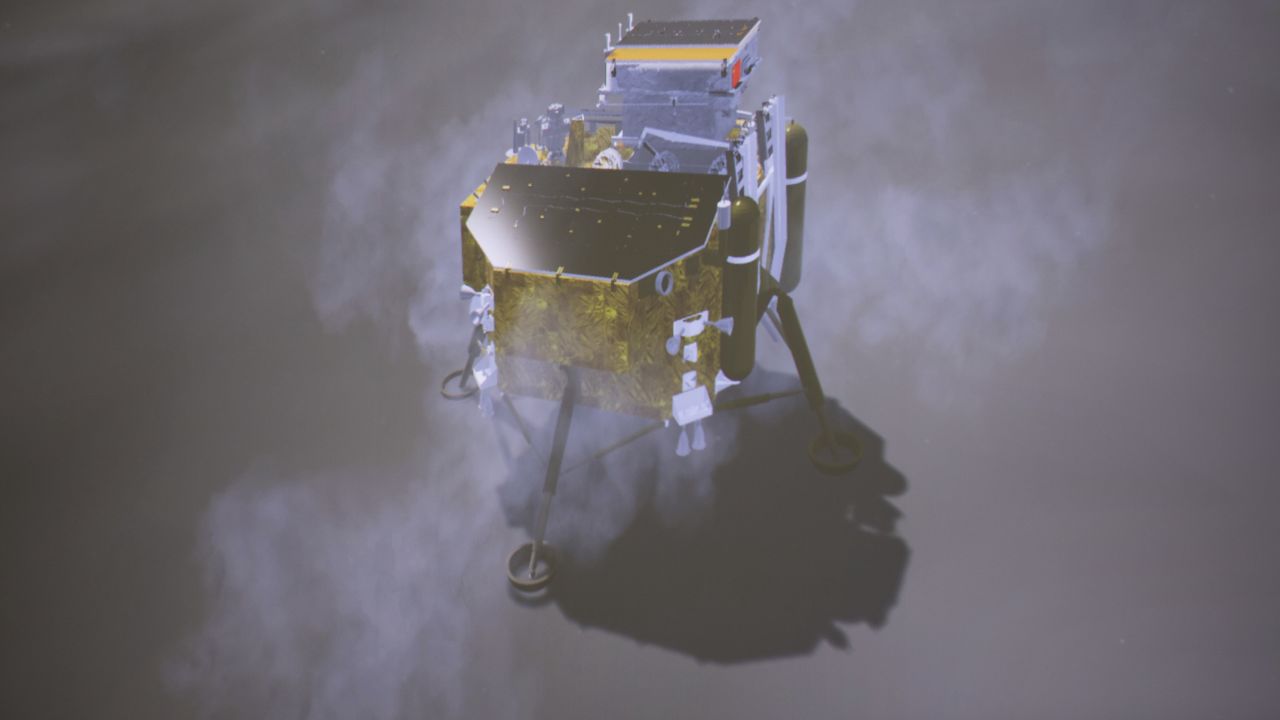

The rover touched down Thursday, delivered to the moon by the Chang’e 4 probe, a historical first for humankind – the far side of the moon has not previously been visited – and a major achievement for China’s increasingly impressive space program.

Thursday’s landing is the first time humanity has landed anything on Earth’s natural satellite since 2013. Its success “opened a new chapter in humanity’s exploration of the moon,” China’s National Space Administration said in a statement.

The front page of Friday’s China Daily, a state-run newspaper, featured a large photo of scientists at the Beijing Aerospace Control Center reacting to the touchdown, alongside one of the first images sent back by Chang’e 4 of the moon’s far side.

Reacting on Twitter, NASA administrator Jim Bridenstine called it a “first for humanity and an impressive accomplishment!”

China was late to the space race – it didn’t send its first satellite into orbit until 1970, by which time the US had already landed an astronaut on the moon – but it has been catching up fast.

Since 2003, China has sent six crews into space and launched two space labs into Earth’s orbit. In 2013, it successfully landed a rover – Yutu 1 – on the moon, becoming only the third country to do so.

While the reaction to Thursday’s landing in China – where economic concerns are becoming increasingly pressing amid an ongoing trade war with the US – was more limited than for the previous lunar mission, the success of Chang’e 4, and the global acclaim it has brought, will be a significant boost to the Chinese space program.

That program will need all the support it can get in coming years as it attempts to realize ambitions that are, appropriately, stratospheric.

Dreams of space

Speaking to astronauts aboard the Shenzhou 10 spacecraft by video link in 2013, Chinese President Xi Jinping said “the space dream is part of the dream to make China stronger.”

“The Chinese people will take bigger strides to explore further into the space,” he added.

Under Xi’s leadership, China has invested billions in building up its space program, even as it asserted its influence back on Earth more aggressively and pursued the “great rejuvenation of the Chinese nation.”

The first stage of China’s space dream largely takes place in our planetary neighborhood.

In 2020, the next lunar mission, Chang’e 5, is due to land on the moon, collect samples and return to Earth, while preliminary plans are underway for a manned lunar mission in the 2030s. If successful, China would become only the second country, after the US, to put a citizen on the moon.

Beijing is also spending big on the Tiangong program, a precursor to a permanent space station it plans to launch either this year or next. The Tiangong 2 space lab has been in orbit for over two years, and is due to return to Earth in a controlled destruction in July 2019.

“Our overall goal is that, by around 2030, China will be among the major space powers of the world,” Wu Yanhua, deputy chief of the National Space Administration, said in 2016.

But despite these big steps forward, China still has a long way to catch up in the space race.

As Chang’e 4 was preparing to descend to the lunar surface, NASA sent back photos of Ultima Thule, the first ever flyby of an object in the Kuiper Belt, a collection of asteroids and dwarf planets a billion miles beyond Pluto.

One achievement could see China leapfrog the US, however, and make history in the progress: landing an astronaut on Mars.

Red planet

Speaking to state TV after Thursday’s lunar landing, Wu Weiren, the mission’s chief designer, said it was “human nature to explore the unknown world.”

Since 1972, that exploration has largely been carried out by robots. Not since Gene Cernan climbed on board the Apollo 17 lunar module to return to Earth has humanity stepped foot on anything outside our planet.

There is a very good reason for this. Robots are cheaper and longer lasting, and can carry out the same observations and experiments as a human astronaut. Most importantly, they don’t die – no one wants to be the first country to leave a corpse on the moon.

This isn’t to say the manned lunar missions were useless – they provided key information on how humans can survive in space, as well as potential dangers and challenges, which helped lead to significant scientific advancements.

Those advancements will be key in delivering a person to Mars, a far, far harder task.

China will make its first visit to Mars with an unmanned probe set to launch by the end of next year, followed by a second mission that would include collection of surface samples from the red planet.

Liftoff

If China is a latecomer to the original space race, it could be kickstarting a new one with its Martian and lunar ambitions.

US President Donald Trump has spoken of his desire to send an astronaut to the red planet, and his administration has called on NASA to focus on its “core mission of space exploration.”

On Thursday, NASA administrator Bridenstine – who was nominated by Trump – responded to a CNN report quoting Joan Johnson-Freese, a professor at the US Naval War College, saying the “odds of the next voice transmission from the moon being in Mandarin are high.”

“Hmmm, our astronauts speak English,” Bridenstine wrote on Twitter.

Russian President Vladimir Putin has also called for his country to land a cosmonaut on Mars, and India too is investing in its space program, with a visit to the moon planned for 2019.

China is also pushing its rivals in other ways. In 2016, it completed work on the world’s largest telescope, which will work to detect radio signals – and potentially signs of life – from distant planets.

In near orbit too, China could soon be leading the way. While its space station is due to launch in coming years, the International Space Station (ISS) is facing a funding squeeze that could see it decommissioned by 2025.

Moon mining

China’s space program is about more than just bragging rights for Beijing.

The moon plays host to a wealth of mineral resources, including rare earth metals (REM) used in smartphones and other modern electronics. China already dominates the global supply of REM, and exclusive access to the moon’s supply could provide huge economic advantages.

In addition to REM, the moon also possesses a large amount of Helium-3, a rare element which can be used for nuclear fusion. According to the European Space Agency (ESA), “it is thought that this isotope could provide safer nuclear energy in a fusion reactor, since it is not radioactive and would not produce dangerous waste products.”

Ouyang Ziyang, a prominent Chinese space scientist and one of the drivers of its lunar program, has long advocated for Helium-3 mining as a reason for moon missions.

“Each year three space shuttle missions could bring enough fuel for all human beings across the world,” he told state media in 2006.

Ultimately, according to Namrata Goswami of the Institute for Defence Studies and Analyses, China wants to “establish alternative institutions, investment mechanisms, and capacities that not only challenge US dominance in space but establish a China-led space order.”