President Omar al-Bashir was addressing his top police officers on Sunday following days of unrest across Sudan. In a video disseminated by the state news agency SUNA, his words sounded remarkably conciliatory.

“It is the duty of the state to maintain security without abuse, and to implement internal security principles using the least possible force,” Bashir told his officers. “The purpose is not to kill the people but the ultimate goal is to maintain the security and stability for the citizens.”

The feed, provided by SUNA, cut off there, but Bashir’s speech wasn’t over.

In a video captured by the Turkish news agency Anadolu and currently making the rounds on Sudanese social media, he continued: “but sometimes – as we said and as God himself said – you have, in the exacting of penance, life. What is exacting penance? It is killing, it is execution, but God described it as life because it is a deterrence to others so we can maintain security.” At the conclusion of his address, the President and his officers began to dance.

But in Bashir’s Sudan, executions are often a “deterrence” enacted without recourse to judge or jury. In the days since anti-government demonstrations began rippling across the country, there have been reports of dozens killed and hundreds more wounded. The fear is now that this toll is set to rise.

Bashir’s speech was taken as a sign by protesters that he had declared open season on them on the eve of mass protests in the capital Khartoum on Monday.

At least 21 activists were released after being arrested in Khartoum for participating in Monday’s demonstrations, a local journalist told CNN. While the total number of arrests remains unclear, activists report that more than 300 protesters were arrested.

The tactics and the language are not new. Bashir’s plain-spoken colloquialisms, backed by recitations from the Quran as justification, are almost as famous as the Arab tribal dances he routinely does with his cane aloft at rallies across the country. They harken back to the early days of his regime, after he came to power in a military coup backed by Islamists in 1989, when he portrayed himself as a man of the people, if one not exactly chosen by them.

In the first few years, Bashir ordered the interrogations and detentions of his opponents, real and imagined, in infamous “ghost houses,” where dissidents were tortured. He also reinforced his rule through the forced recruitment of northern Sudanese boys as he waged war against the country’s south, portraying it as an existential battle for the Muslims of Arab descent in the north.

As different conflicts erupted across the country throughout his rule – Darfur, South Kordofan, Blue Nile – Bashir became increasingly worried that his army could not be trusted to back him. Its ranks were filled with boys and men from historically marginalized regions, where Bashir’s Arab-centric imagery and tribal leader self-mythologizing rang hollow.

So Bashir began to rebuild.

A new paramilitary group, known as the Rapid Support Force, was created out of the remnants of the Janjaweed tribal militias in Darfur. Their leader, Mohammed Hamdan “Hamadti,” was made an adviser to the President, in spite of accusations of his involvement in atrocities in Darfur.

Elite units known as “Abu Tayra” were added to the police force. The country’s national security agency also gained a special forces unit under the aegis of Sudan’s commander in chief – Field Marshal Omar al-Bashir.

These newly built units were more directly controlled by Bashir than traditional law enforcement agencies, and largely consisted of young men from tribes of Arab descent, playing directly in to Bashir’s policy of tribally dividing and conquering.

This policy has been reinforced in recent days by the parading across state television of Darfuri students of non-Arab descent, accused of being “the foreign agents” responsible for the demonstrations and unrest.

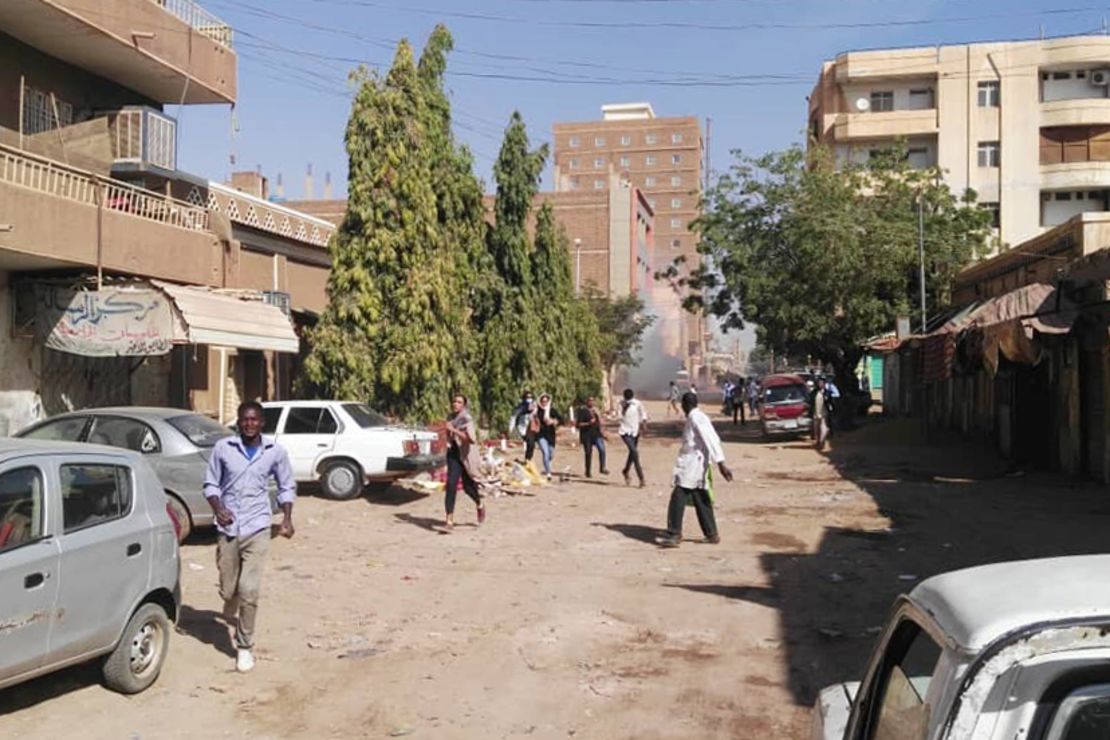

All of this has now been unleashed against the demonstrators currently challenging his rule, with a few added extras – the snipers and the “ghost squads,” young men in plain clothes patrolling the streets in government issued pick-up trucks.

Eyewitnesses described beatings and detentions by these men, along with the helplessness of not knowing who to hold accountable or who to blame. Others described seeing plain-clothed snipers stationed on buildings along protest routes in towns across Sudan. One even found a sniper stationed on the roof of his office building, without his knowledge.

The marches, for now though, continue. All ages and all professions are out in the streets, united with one call: it’s time for Bashir to go.