It has taken more than 20 years to extract, assemble and interpret a mysterious find from a famed marble quarry about 50 miles north of Milan, Italy. Now, with the investigation finally complete, Italian paleontologists say the fossils discovered in 1996 by an amateur fossilist, Angelo Zanella, are from a new species of dinosaur with four-fingered hands that offer clues to how modern bird wings evolved.

A new species warrants a new name. This one is “Saltriovenator zanellai,” with “Saltrio” referring to the Italian municipality of discovery, “venator” meaning hunter in Latin and “zanellai” honoring Zanella.

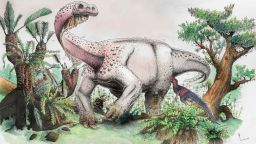

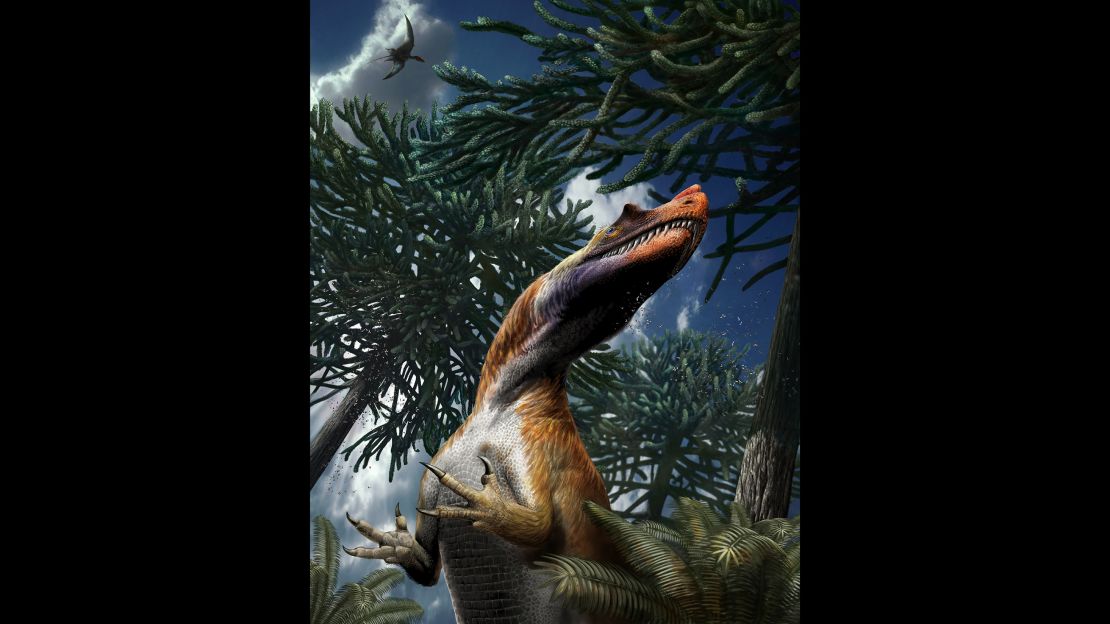

Saltriovenator zanellai, which lived about 200 million years ago during the dawn of the Jurassic period, was “a fierce, large predator” that spanned nearly 8 meters in length (26 feet) and possessed an 80-centimeter skull (more than 2½ feet long), according to the study authors. The 1-ton meat-eater was armed with sharp teeth and had forelimbs with four fingers, three of which formed powerful claws.

Saltriovenator is the first Jurassic dinosaur from Italy and the most ancient predatory dinosaur of large size yet discovered, said lead study author Cristiano Dal Sasso of Milan’s Natural History Museum. His team’s research was published Tuesday in the journal PeerJ.

“Saltriovenator predates the massive meat-eating dinosaurs by over 25 million years and sheds light on the evolution of the three-fingered hand of birds,” Dal Sasso said in a statement.

Putting the pieces together

Extracting the find from the quarry – which, in 1778, supplied marble slabs for the renowned La Scala Opera House – required 1,800 hours of chemical preparation on more than 300 kilograms (661 pounds) of rock. The result: 132 bone pieces, a dozen rib fragments and 35 bones.

Dal Sasso performed a painstaking and systematic analysis, fragment by fragment, to recompose and position the bones. He even went to the University of California Museum of Paleontology in Berkeley and the National Museum of Natural History in Washington to consult more complete dinosaur skeletons.

“Not all fragments match, but many are adjacent and allow us to virtually reconstruct the shape of whole bones,” Dal Sassosaid in a statement. “To complete the puzzle we also used a 3-D printer: part of the left scapula was turned into the right one thanks to a ‘mirroring printing’ which gave us a more complete scapula.” The final illustrations were made by combining more than 150 image files, he said.

What did this region look like during the Jurassic period?

Geologists believe that nearly 200 million years ago, tropical beaches were interspersed with lush forests in the Western Lombardy region where the fossils were discovered. Much of the rock that forms the Alps and the Himalayas was deposited on the margins of the Tethys Ocean, a vast ocean that once lay south of Europe and Asia and north of Africa and India. Saltriovenator helps confirm these hypotheses.

For example, feeding marks made by marine invertebrates cover the bones of Saltriovenator. Never seen before on dinosaur remains, these marks indicate that the carcass floated in a marine basin and then sank to the sea floor, where it remained for months or even years before becoming buried and fossilized.

Fossil leaves from large primitive conifers found in same-age rock layers surrounding the fossil also suggest that land emerged from a shallow sea at the beginning of the Jurassic period.

How does Saltriovenator help explain bird wing evolution?

Modern birds are descended from dinosaurs. The two have skeletal traits in common, including hollow bones, and they share “other biological and behavioral features, such as nest building and brooding behavior,” Dal Sasso wrote in an email. Dinosaurs – “we should say extinct non-avian dinosaurs, because birds are dinosaurs too” – also evolved feathers.

Meat-eating dinosaurs, including Saltriovenator, belong to a group of two-legged dinosaurs known as theropods. Scientists believe that during their evolution, theropods lifted their forelimbs off the ground and modified them for catching prey, and bird wings evolved from there.

Two competing hypotheses explain the evolutionary chain of events, Dal Sasso said. One proposes that the wing evolved from the fusion of the first, second and third fingers of the theropod hand. The second theory suggests wings arose from the second, third and fourth fingers. Saltriovenator, which demonstrates an early stage in the theropod hand, suggests that the small fourth finger of early theropods disappeared as theropods evolved, while their first three fingers gave rise to bird wings.

Hans Sues, senior research geologist and curator of vertebrate paleontology at the National Museum of Natural History, wrote in an email that “there are now many fossils that show how birds evolved from small meat-eating dinosaurs.” Sues, who edited the study manuscript, noted that the oldest known bird is the “150-million-year-old Archaeopteryx, which has fully developed wings but otherwise is still extremely similar to certain dinosaurs.”

The new find is “one of the oldest known large meat-eating dinosaurs and the first of this kind from Italy,” Sues said. And, although it may seem surprising that a non-professional found its bones, he said, “amateurs often find fossils as they often live in or near places that have rocks with fossils and can look there many times.”

Of course, the professionals help keep the flame of discovery burning. “We still lack skeletal remains of armoured dinosaurs but we know that they lived also in Italy because many footprints have been recovered,” Dal Sasso wrote in email. “It is just a matter of time, I hope.”