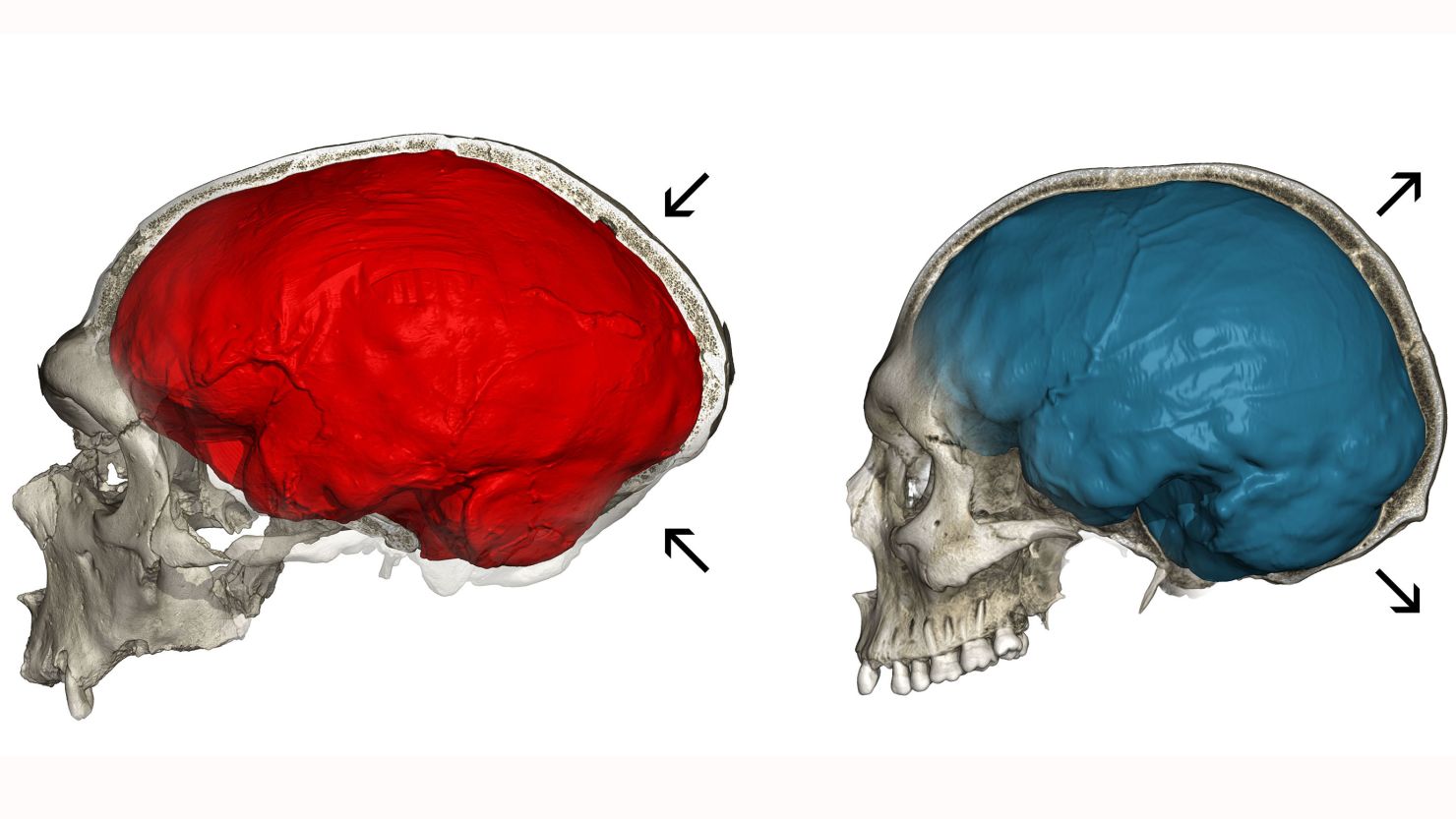

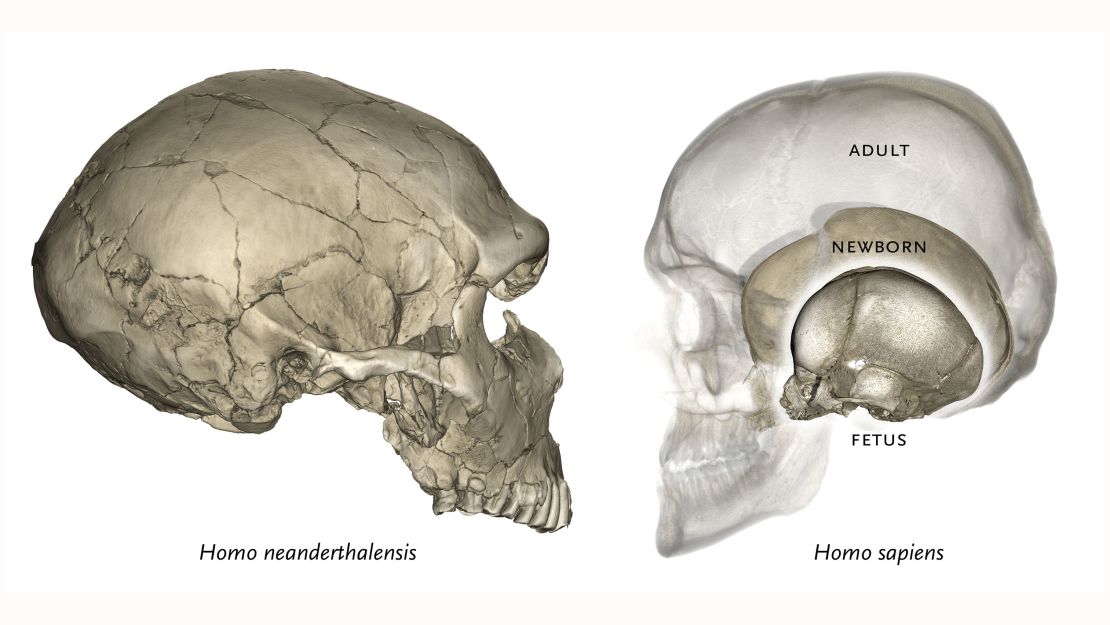

Humans have unusually globular (or round) skulls and brains compared to our ancient ancestors – including our closest extinct cousins the Neanderthals – and a new study provides a possible explanation as to why.

For the first time, an interdisciplinary team of scientists have identified two genes that affect the shape of the modern human’s skull – and they originate from Neanderthals.

“Billions of people living today carry a small fraction of Neanderthal genes in their genome – a distant echo of admixture when our ancestors left Africa and encountered Neanderthals,” said study author Philipp Gunz, a paleoanthropologist at the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology in Leipzig, Germany, via email.

These are typically humans with European ancestry stemming from interbreeding between Neanderthals and modern Europeans.

“By combining data from fossils, genetics and brain imaging we can learn something about evolutionary changes to brain development in our own species,” said Gunz.

The team used MRI scans to analyze the cranial shape of about 4,500 peoples’ brains before looking at their genomes to work out which fragments of Neanderthal DNA they carried.

They also studied fossil skulls and ancient genomes to compute the shapes of both Neanderthal and modern human skulls for comparison and then looked at whether any particular genes were linked to less globular brain shape in the people that carried them.

They found two genes variants that have a subtle effect on skull shape, on chromosomes one and 18, which when disrupted have major consequences for brain development, according to the research.

“It gives us our first glimpse of how genes might contribute to this particularly striking aspect of the anatomy of our species,” said Simon Fisher, director of the Max Planck Institute for Psycholinguistics, which co-led the research.

The gene variants found on chromosomes one and 18 are linked to the expression of two nearby genes called UBR4 and PHLPP1 that affect the formation of new nerve cells and their insulation.

“We would like to understand more about globularity because it might relate to specific changes in the ways our brains are organized – the relative sizes of different parts of the brain and how they are connected to each other, as compared to our ancestors.”

But Fisher is keen to emphasize that the study does not mean that people with a more elongated skull have more Neanderthal DNA, nor can behavior be explained by skull shape. Instead, the team set out to evaluate the effect of skull globularity on the distinctive brain biology of modern humans.

Gunz told CNN that there are potential links between evolutionary changes in skull shape and brain regions involved in the preparation, learning and coordination of movements, as well as cognitive functions such as memory, attention, planning and potentially speech and language evolution.

“This is certainly an important study, showing how fragments of Neanderthal DNA have a direct effect on the brain form (and presumably brain function) of people today,” said professor Chris Stringer, a paleoanthropology specialist at the Natural History Museum in London who was not involved in the study.

“The research shows how the evolutionary change to a globular brain shape in modern humans (and reflected in a more globular braincase in fossil humans) was a complex multi-stage process rather than a simple switch,” he added.

The latest study also builds on previous research that has improved our knowledge of our human ancestry.

A piece of 2017 research by scientists at the US National Institute of Mental Health said that the more Neanderthal genes present in a person’s genome, the more their brain and skull resemble those of the Neanderthals.

While these Neanderthal genes are thought to boost brain regions that allow us to visualize objects and use tools, the researchers say that this development may come at the expense of a cognitive deficit that may help to explain schizophrenia and autism-related disorders.

Get CNN Health's weekly newsletter

Sign up here to get The Results Are In with Dr. Sanjay Gupta every Tuesday from the CNN Health team.

And a 2017 study by anthropologists at the University of California Davis said that our skulls changed shape when farming began in earnest. This is because it takes less effort to chew the softer diet of farmers, particularly dairy products, compared to a hunting and foraging diet, which makes for smaller jaw bones.

In 2018, researchers dispelled the myth that Neanderthals lived more dangerous, violent lives than humans, and another study used CT scans of fossils to reveal that Neanderthals may not have sported the barrel-chested bodies and hunched posture we see in museums and textbooks.

CNN’s Ashley Strickland and Meera Senthilingam contributed to this report.