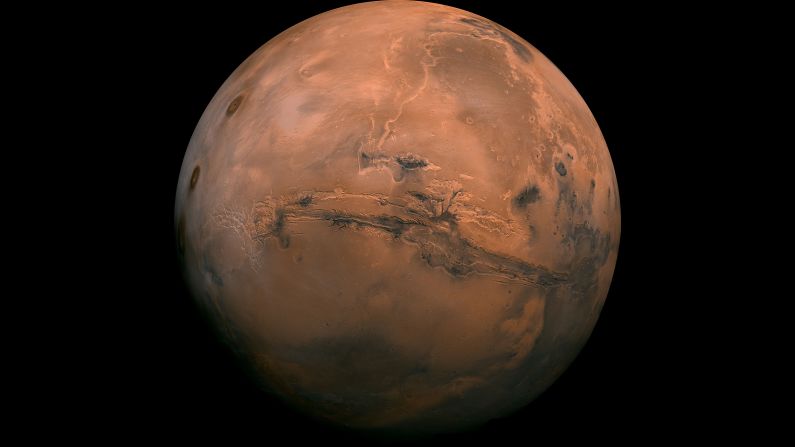

For the first time in six years, a new mission is about to land on Mars. On November 26, NASA’s Mars InSight lander will touch down on the Red Planet at 3 p.m. EST.

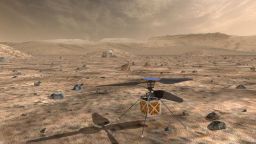

InSight, or Interior Exploration using Seismic Investigations, Geodesy and Heat Transport, is going to explore a part of Mars that we know the least about: its deep interior. It launched May 5.

“When InSight drills down into the Martian soil, we’ll learn more about how Mars and Earth formed. We’ll know more about where we all came from, and why these two rocky worlds are so similar yet so different,” Bill Nye, CEO of the nonprofit Planetary Society, said in a statement. “We may learn more about what kinds of planets can harbor life. InSight is more than a Mars mission – it’s a solar system mission.”

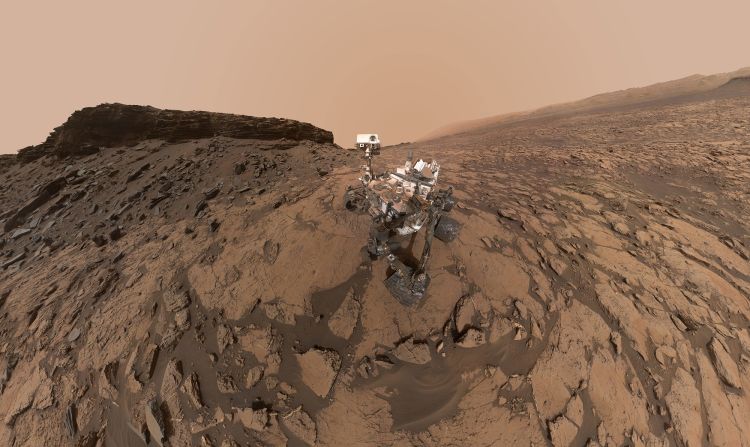

NASA will provide live coverage from mission control, and there are landing watch parties around the world. In 2012, there were similar events to celebrate the Mars Curiosity rover’s landing.

What is InSight?

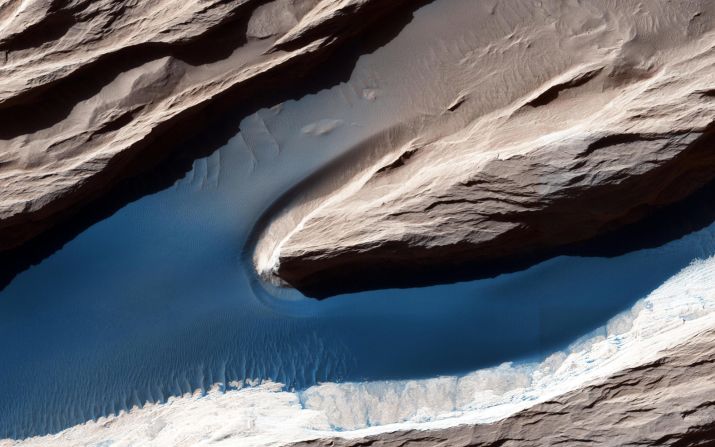

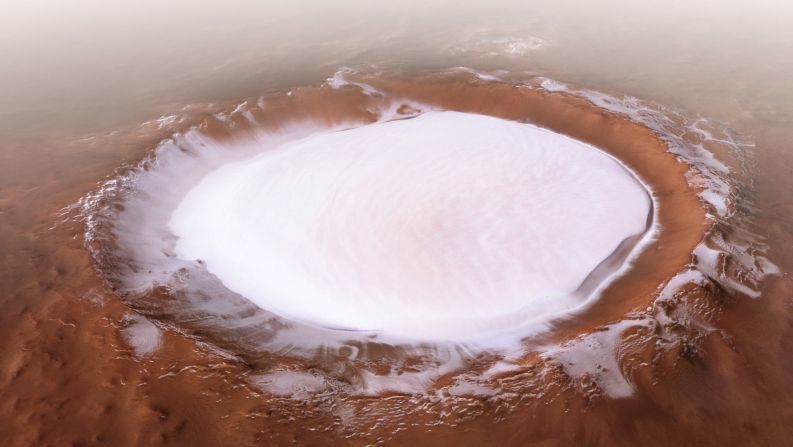

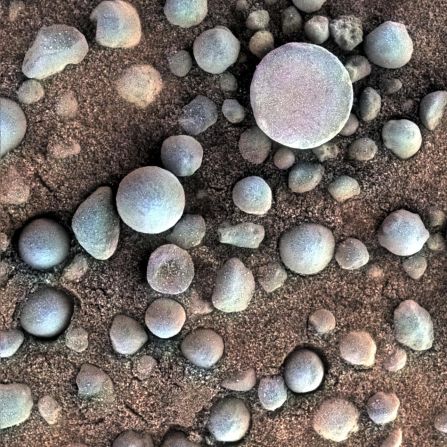

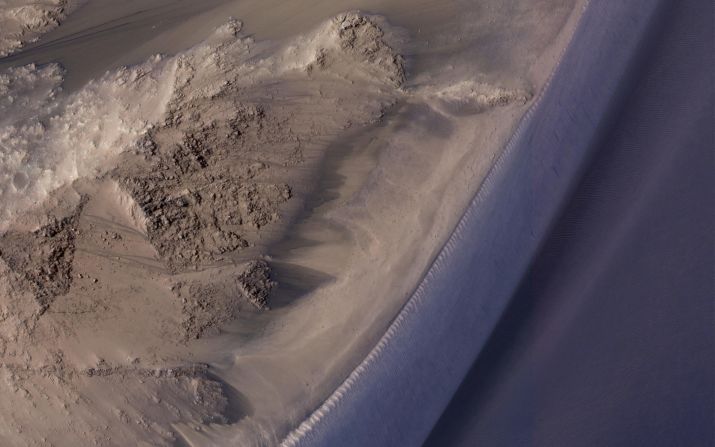

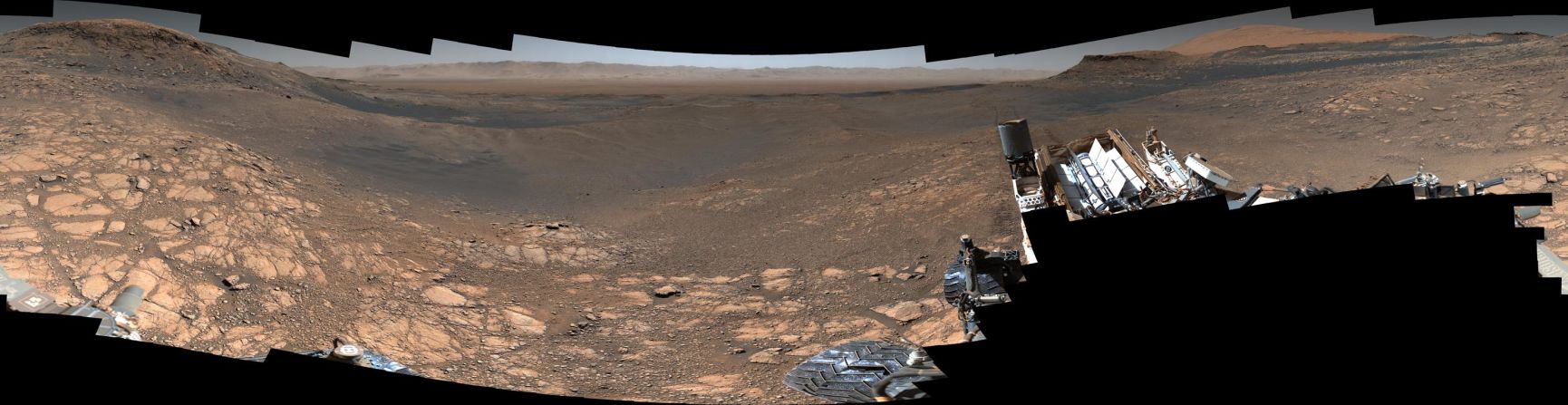

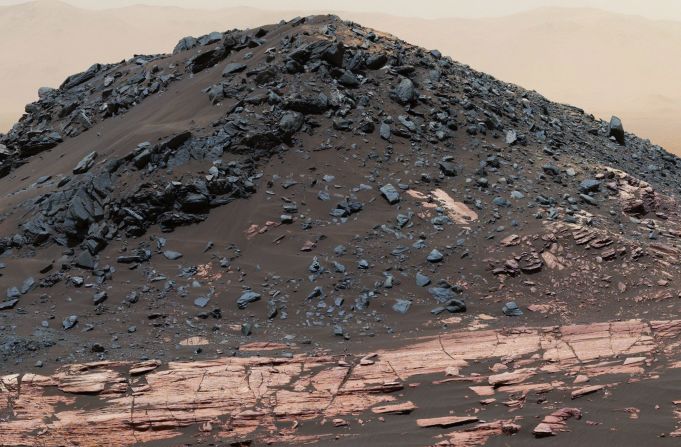

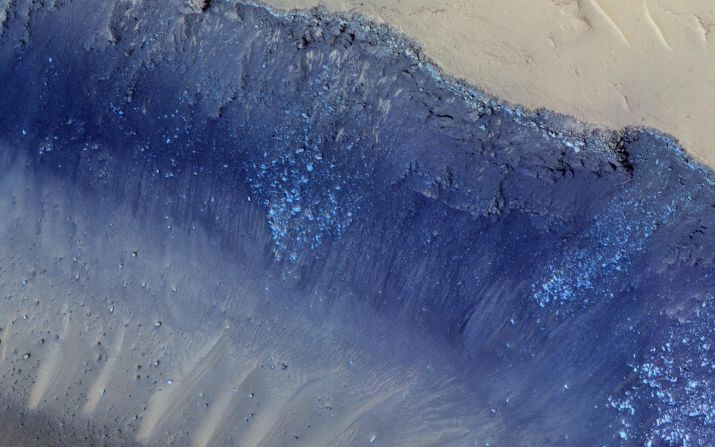

Missions like the rovers have provided a great look at the surface, including Mars canyons, volcanoes, soil and rocks, but it’s the building blocks below the surface that record the planet’s history. InSight will spend two years investigating the interior.

Like on Earth, there are stories locked in the Martian core, mantle and crust. But the history of Mars may be more complete than Earth’s because the Red Planet has been less geologically active.

Mars was chosen for the mission because of this complete record, which is similar to the formation of Earth, Venus, Mercury and the moon. InSight can also investigate the planet’s tectonic activity and meteorite impacts.

And this isn’t just about Mars. InSight will give us a deeper understanding of how the rocky planets in our inner solar system formed more than 4 billion years ago, like Earth.

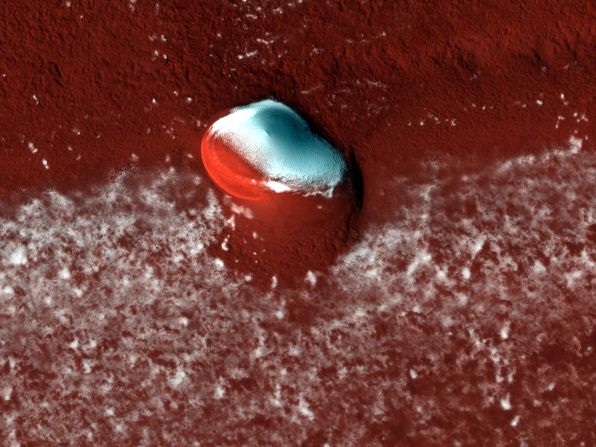

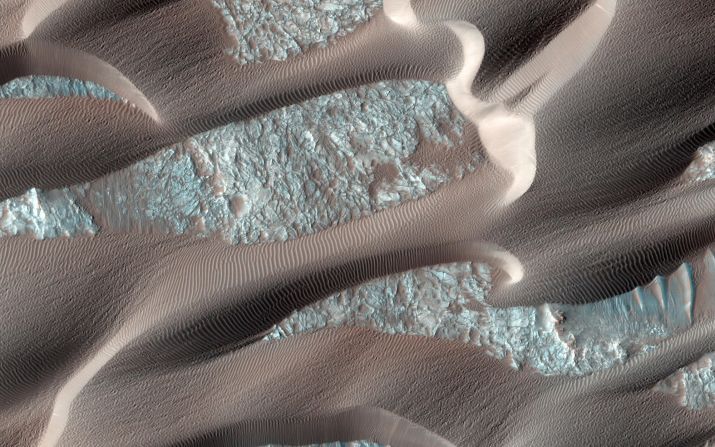

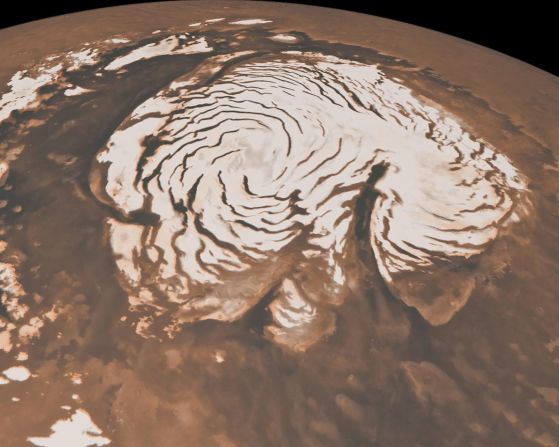

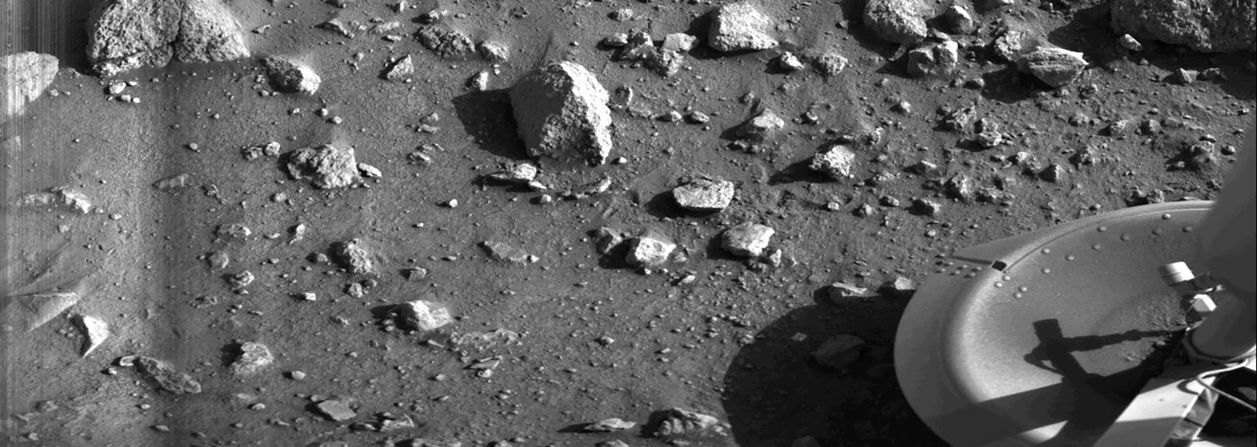

It’s similar in design to the Mars Phoenix Mission, which studied ice near the Martian north pole in 2008.

The best photos of Mars

MarCO is along for the ride

InSight isn’t alone on this mission. Two suitcase-size spacecraft, called MarCO, are cube satellites following InSight on its journey. They are the first cube satellites to fly into deep space. MarCO will try to share data about InSight when it enters the Martian atmosphere for the landing.

During InSight’s entry, descent and landing, the lander will be transmitting information to the Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter that’s now circling Mars. But the orbiter can’t receive and transmit data at the same time, which would delay the news of the landing by about an hour.

However, MarCO can receive and transmit immediately.

“MarCO-A and B are our first and second interplanetary CubeSats designed to monitor InSight for a short period around landing, if the MarCO pair makes it to Mars,” said Jim Green, director of NASA’s Planetary Sciences Division. “However, these CubeSat missions are not needed for InSight’s mission success. They are a demonstration of potential future capability. The MarCO pair will carry their own communications and navigation experiments as they fly independently to the Red Planet.”

The landing: What to know

Landing on Mars is incredibly difficult. Only 40% of missions sent to the Red Planet by any agency have been successful.

Part of this is due to the thin Martian atmosphere, which is only 1% of Earth’s, so there’s nothing to slow down something trying to land on the surface.

The United States is the only country to have missions that survived landing on Mars, and NASA has been flying past, orbiting, landing and roving over Mars since 1965.

Like the Phoenix spacecraft, InSight will have a parachute and retro rockets to slow its descent through the atmosphere, and three legs suspended from the lander will try to absorb the shock of touching down on the surface.

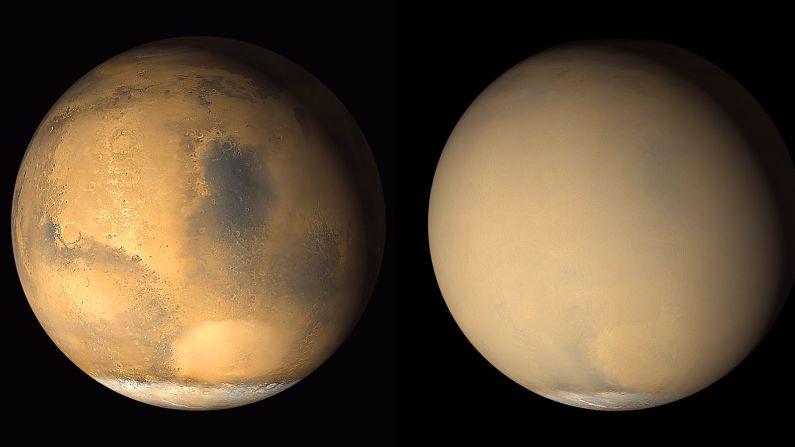

But the engineers prepared the spacecraft to land during a dust storm if need be.

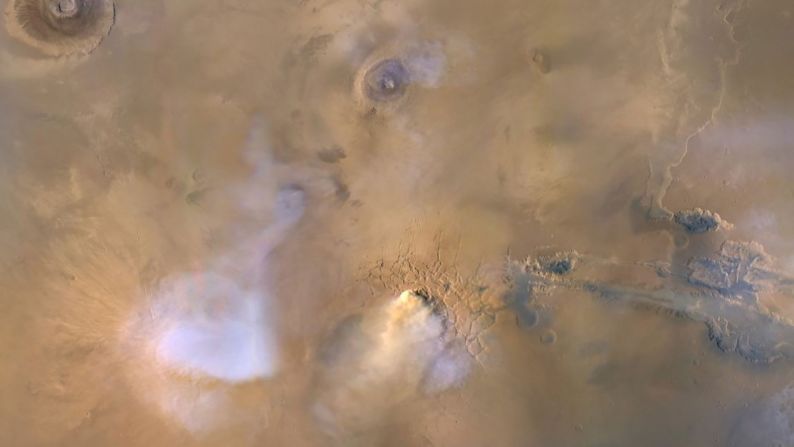

Mars is known for its dust storms, some of which can be planet-encircling like one that began in May and has temporarily suspended the Opportunity rover’s functions.

Tweaks to the original Phoenix design included the heat shield and parachute. The heat shield is thick, capable of being sandblasted by a Martian dust storm, while the suspension lines of the parachute are stronger to cope with air resistance.

InSight won’t have a blind landing. The Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter will send weather updates to the mission team in the days before, allowing the team to change when the parachute deploys.

InSight’s new home

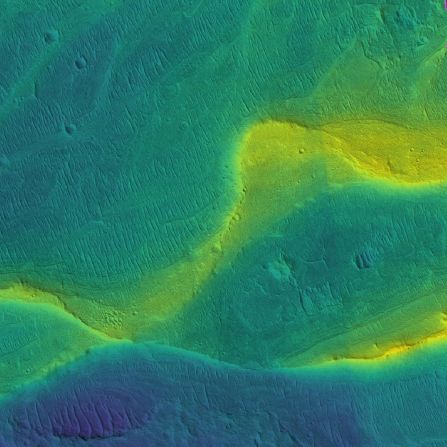

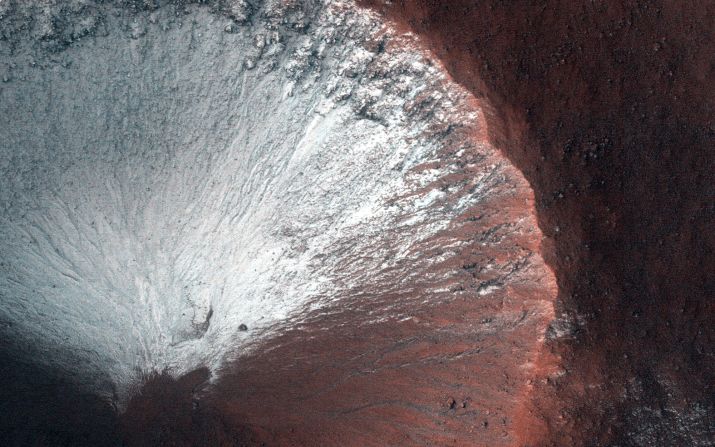

InSight will be landing at Elysium Planitia, called “the biggest parking lot on Mars” by astronomers. Because it won’t be roving over the surface, the landing site was an important determination. This spot is open, flat safe and boring, which is what the scientists want for a stationary two-year mission.

“If Elysium Planitia were a salad, it would consist of romaine lettuce and kale – no dressing,” said InSight principal investigator Bruce Banerdt of NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory. “If it were an ice cream, it would be vanilla.”

After landing, InSight will unfurl its solar panels and robotic arm and study the entire planet from its parking spot. It’s along the Martian equator, bright and warm enough to power the lander’s solar array year-round.

The suite of geophysical instruments on InSight sounds like a doctor’s bag, giving Mars its first “checkup” since it formed. Together, those instruments will take measurements of Mars’ vital signs, like its pulse, temperature and reflexes – which translates to internal activity like seismology and the planet’s wobble as the sun and its moons tug on Mars.

These instruments include the Seismic Experiment for Interior Structures to investigate what causes the seismic waves on Mars, the Heat Flow and Physical Properties Package to burrow beneath the surface and determine heat flowing out of the planet, and the Rotation and Interior Structure Experiment to use radios to study the planet’s core.

InSight will be able to measure quakes that happen anywhere on the planet. And it’s capable of hammering a probe into the surface.

“Picking a good landing site on Mars is a lot like picking a good home: It’s all about location, location, location,” said Tom Hoffman, InSight project manager at JPL. “And for the first time ever, the evaluation for a Mars landing site had to consider what lay below the surface of Mars. We needed not just a safe place to land, but also a workspace that’s penetrable by our 16-foot-long heat-flow probe.”