You may have thought Big Bird was unrealistically gigantic, but he’s still not the largest bird to ever walk the Earth. That honor goes to elephant birds, which stood 10 feet tall and roamed Madagascar thousands of years ago.

For reference, “Sesame Street’s” Big Bird stands at 8 feet, 2 inches.

New research suggests that the giant flightless birds, which went extinct between 500 and 1,000 years ago, were also nocturnal and blind. An analysis of two elephant bird skulls from two species was published Tuesday in the journal Proceedings of the Royal Society B.

“As recently as 500 years ago, very nearly blind, giant flightless birds were crashing around the forests of Madagascar in the dark. No one ever expected that,” said Julia Clarke, study co-author and professor at the University of Texas Jackson School of Geosciences.

It had been believed that these birds were similar to emus and ostriches; they’re also big, flightless birds, but they’re active during the day and have good eyesight. But this new research sheds light on elephant birds as being closer in relation to kiwis – also nocturnal with poor vision. Kiwis, which are about the size of chickens, live in New Zealand.

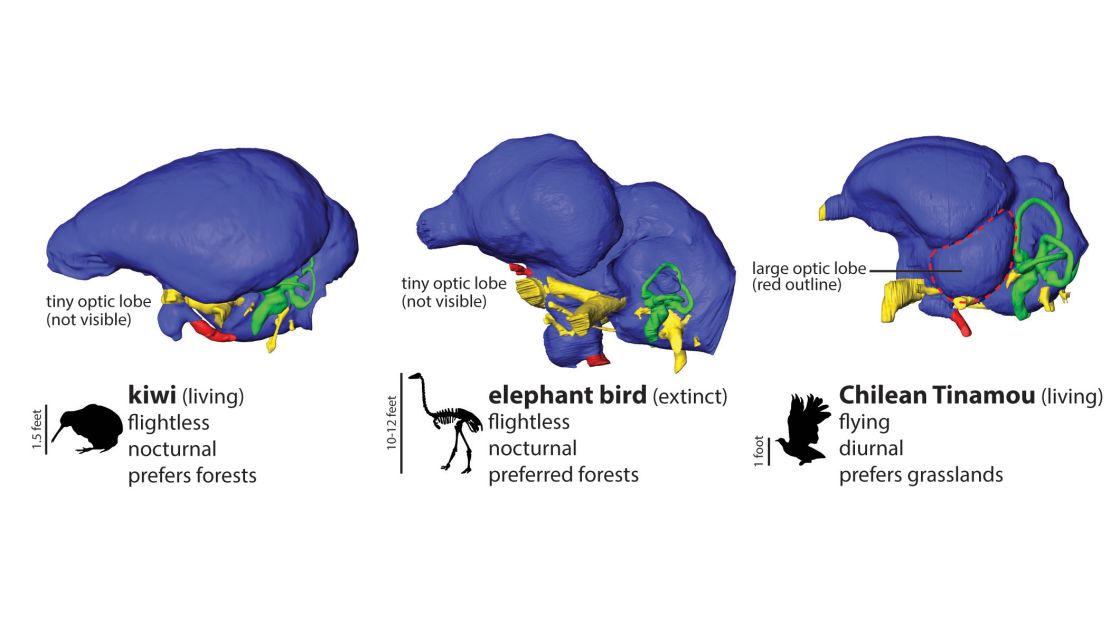

Because bird skulls fit tightly around their brains, the shape of the skull correlates to the structures of the brain. Brain reconstruction research in elephant birds revealed that their optic lobes, the nerves that control eyesight, were incredibly small and almost absent. This is very similar to the kiwi.

“Certainly, the most surprising was just how small the elephant bird’s optic lobes were,” said Christopher Torres, study co-author and Ph.D. candidate at the University of Texas at Austin. “The few studies that speculated on what their behavior was like explicitly assumed they were active during the day. Then, once we made the connection to nocturnality, we were blown away. It meant revising more than century’s worth of attempts at reconstructing the elephant bird lifestyle.”

So how did elephant birds become nocturnal?

“A nocturnal lifestyle is often an evolutionary response either when it’s too dangerous to come out during the day or when what you eat comes out at night,” Torres said.

But elephant birds had no known predators and were plant-eaters.

In this case, nocturnality is probably an inherited trait from the ancestor shared by elephant birds and kiwis. And sometimes, competition between species can cause extremes in evolution.

The researchers recognized a pattern in which these birds undergo a nocturnal phase, caused by a sensitivity to light, that allows them to see in low-light conditions, Torres said. In flightless birds, their visuals are reduced, and they rely on other senses.

They also looked at the larger group of birds including ostriches, emus, cassowaries, rheas, kiwi, moa and tinamous, in which a relationship between the development of the sense of smell and habitat preference formed.

“Species in this group that live in forests seem to rely on a well-developed sense of smell to help them forage in conditions where visual cues might be obstructed,” Torres said.

The next mystery concerns why elephant birds went extinct, and it remains unsolved. But scientists have clues pointing to hunting and habitat destruction by humans, as well as climate change.

At the time, Madagascar’s climate was still changing, and humans hadn’t reached the point where they could affect global climate change.

“Recent studies have suggested that elephant birds outlived initial contact with humans by many thousands of years based on toolmarks observed on radiometricly dated remains,” Torres said.

And knowing that elephant birds were nocturnal also helps explain why they were able to coexist with humans for so long. Other birds were not so lucky. The moa, nine species of flightless birds, were apparently gone within a handful of centuries after humans made it to New Zealand, he said.

Going forward, Torres wants to take a deeper look at the strange evolutionary stories of creatures like elephant birds.

“Studying brain shape is a really useful way of connecting ecology – the relationship between the bird and the environment – and anatomy,” Torres said. “Discoveries like these give us tremendous insights into the lives of these bizarre and poorly understood birds.”