Story highlights

At 9 inches long, "Andrew" is the smallest Diplodocus skull ever found

Baby dinosaurs weren't simply smaller versions of adults

Andrew, a baby dinosaur fossil, has quite a story to tell.

Sadly, there isn’t much of him left now, considering he lived during the Jurassic Period. His skull was found in the Upper Jurassic Morrison Formation in Montana, where other dinosaur fossils have been recovered.

A study of the skull, which is just over 9 inches long, was published Thursday in the journal Scientific Reports.

“This skull is the smallest Diplodocus skull ever found,” said Cary Woodruff, study author and director of paleontology at the Great Plains Dinosaur Museum in Montana. “It’s not just its size that’s important; its overall proportions and especially the teeth help us to better understand how Diplodocus grew up.”

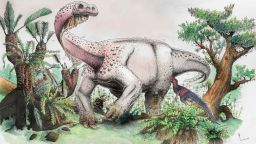

By observing the skull of the young Diplodocus, which is a long-necked sauropod like Brontosaurus, the team discovered that baby dinosaurs were a lot different than their parents – not merely smaller versions of them.

Diplodocus skulls are rare, and it’s even more rare to find one belonging to a young one.

The overall proportions and bone shapes suggest that the skull of Diplodocus underwent a lot of shape change through growth into adulthood, Woodruff said.

Though the adults are known for the peg-like teeth at the front of their mouths, Andrew had those as well as spatulate teeth at the back of his mouth.

“We think this combination of tooth forms indicates that young Diplodocus were feeding on a wider variety ofplant types,” Woodruff said. “Which makes sense. These young dinosaurs are growing super fast, so a young Diplodocus could quite literally eat ‘all of its veggies’ to fuel its rapid growth rate.”

Spatulate teeth can handle coarse vegetation and bulk feeding, rather than the soft foliage and grazing that are suited for peg-like teeth.

Andrew had a short narrow snout, whereas his parents had wide, square snouts. His snout was suited to forests, but his parents would be grazing the ground in open areas.

But if adults fed their babies, why would they need to have different teeth and snouts? The researchers believe that the babies fended for themselves and were separated from the adults.

The babies most likely lived in forests in age-segregated herds, which could protect them both from predators and from being trampled by their own gigantic parents.

“I’ve been thinking of these roving bands of young Diplodocus in the forests akin to Peter Pan’s Lost Boys,” Woodruff said. “These age-segregated herds likely sought refuge in more forested areas where they could hide and be more concealed, opposed to being out in the open.”

When the researchers first tested the skull in several ways to see what kind of sauropod Andrew was, they couldn’t reach a definitive answer. They also wondered whether he might be a dwarf specimen of the species rather than a juvenile.

“Parts of it look like Diplodocus; other parts not so much,” Woodruff said. “At the end of the day, we believe we presented enough data to say that more characteristics of Andrew are likewise seen in Diplodocus than any other sauropod. We also show attributes, including the internal aspects of the bone, that demonstrate that Andrew is not an adult.”

The discovery of Andrew is helping fill some gaps in the fossil record for Diplodocus, but there are still many questions Woodruff would like to answer.

“Andrew represents a critical piece of the puzzle for understanding how young sauropods like Diplodocus grew up,” he said. “But that story is far from complete, and I want to know more about the intimate life history details of a Diplodocus’ entire life.”

There’s also a reason for his name. Although all museum specimens get an ID number, so do humans, but we don’t go by them, Woodruff said. A name like Andrew makes it more personal, and the museum wanted to share Andrew’s story.

“Andrew specifically is a nod to the philanthropist Andrew Carnegie,” Woodruff said. “Carnegie funded many paleontological expeditions (many for sauropods in Utah), and he even has a species of Diplodocus named in his honor: Diplodocus carnegii. So naming our specimen Andrew was a nod to Carnegie, and a nod to our calling Andrew a Diplodocus.”