US President Donald Trump went off topic in characteristic style at the United Nations Security Council this week, accusing China of using state media to meddle in the upcoming midterm elections.

While he provided no evidence for his remarks, which derailed a meeting that was supposed to focus on issues of nonproliferation, he later accused China on Twitter of “placing propaganda ads in the Des Moines Register and other papers, made to look like news.”

He was referring to an insert from the state-run China Daily placed in a recent Sunday edition of the Iowa paper, which featured stories promoting the benefit of US-China trade, warned of the potential market losses caused by a trade war, and highlighted Chinese President Xi Jinping’s long relationship with the state, among other less news-worthy columns.

Political analysts largely agreed the insert was intended to put pressure on the White House by targeting key Republican districts that will be most affected by a drawn-out trade war with China.

“I think it’s trying to maximize pressure on the administration to change its trade policies toward China by attempting to show White House and Republicans that they’re going to pay a price with the mid-terms,” David Skidmore, a political science professor at Drake University, told the Des Moines Register in a piece by the paper about the insert.

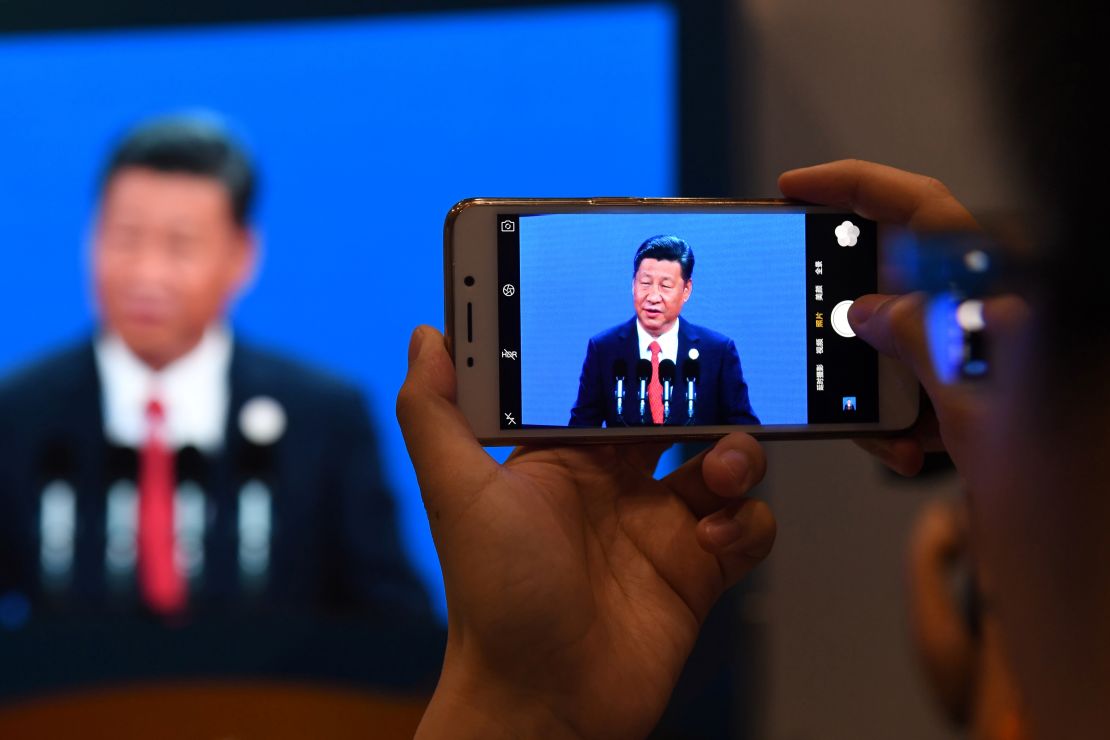

On Wednesday, Xi himself extolled state media’s “contributions to the cause of the Party and the people,” and praised television workers in “promoting in-depth integration and innovation in international communication to present a true, multi-dimensional and panoramic view of China.”

While there is no evidence Xi is attempting to influence US elections, Trump is absolutely correct that Beijing uses its media to shape foreign opinions of China – what he left out, however, is that Washington does as well with its own government-funded media.

Telling China’s story

While it may have been a novelty to some newspaper readers in Iowa, China Daily is a major newspaper, founded in 1981 it is now published in 12 editions across Asia, Europe, Africa and the US.

Unlike most other English-language state media, like broadcaster CCTV or the Global Times, China Daily is not an offshoot of a domestic product but has always targeted foreign readers.

Today, it claims a circulation of around 800,000, with the majority of readers overseas. The paper’s blue vending machines are ubiquitous in Washington DC and parts of New York and other US cities, and it is also often given out for free in hotels and by airlines around the world.

This reach is further extended by China Watch, which the newspaper describes as a “monthly publication distributed to millions of high-end readers as an insert in mainstream newspapers.” These include major US and British titles, such as the Washington Post, and the UK’s Daily Telegraph, giving the insert a reach of 4 million readers, according to China Daily.

By comparison, in 2016 USA Today, the top English-language daily in the world, had a circulation of around 4.1 million, while the New York Times had a circulation of 2.1 million.

China Daily did not immediately respond to a request for comment.

Trump isn’t the first to complain about China Watch. Critics have accused newspapers of failing to highlight to readers that it is a paid insert, or distinguish its content from their own, especially online. On the website of the UK’s Daily Telegraph for example, branding is the same as stories produced by the paper’s own journalists, except for a disclaimer in small text at the top of the page reading “this content is produced and published by China Daily, People’s Republic of China, which takes sole responsibility for its contents,” and a similar disclaimer at the bottom of the article.

The Daily Telegraph did not immediately respond to a request for comment regarding their China Watch sections. A spokeswoman for the Washington Post said the section was clearly marked as not involving “the news or editorial departments of The Washington Post,” adding the China Watch section differs in layout and format “from our editorial content in a number of ways, including headline style, body font and column width.”

Of course, publishing something and having people read it are completely different things, as many media companies have learned to their chagrin. But no matter its reach, China Daily clearly has the backing of Beijing, expanding overseas staff and advertising even as other newspapers slash costs and lay off employees.

Going out

While it was China Daily which drew Trump’s attention, it is not the most important outlet in Beijing’s state media strategy. That title belongs to state broadcaster CCTV, and its international offshoot CGTN. (CNN has an affiliate relationship with CCTV.)

As Ying Zhu recounts in her book about the network, “Two Billion Eyes: the story of China Central Television,” beginning in the early 2000s, Chinese state media was encouraged to “play in the same global pond as CNN, the BBC, and other big Western media firms.”

This was influenced by then-President Jiang Zemin’s call to “let China’s voice broadcast to the world,” a strategy which finally reached its zenith this year with the creation of Voice of China, a new super bureau combining three state-run networks, CCTV, China National Radio and China Radio International.

Of particular attention for this effort has been Africa, where CGTN, China Daily and state news agency Xinhua have all invested heavily. As I document in my book “The Great Firewall of China: How to Build and Control an Alternative Version of the Internet,” this propaganda push has coincided with an increase in internet controls and censorship on the continent, often actively assisted by Beijing.

Like China Daily, CGTN receives a large amount of state funding, which it has used to expand massively. It now broadcasts in more than 180 countries and regions around the world, and is currently building an expensive new London headquarters.

But as with its newspaper sibling, broadcasting in a country doesn’t necessarily mean anyone is watching.

While accurate global viewership figures are difficult to come by, CGTN claims its English-language offerings can be seen in more than 140 million homes internationally.

By comparison, CNN International reaches more than 373 million households worldwide, while the BBC claims a global audience of 376 million.

Russian state broadcaster RT, a frequent bogeyman in US political discourse, also knocks CGTN out of the park on YouTube, where the Chinese network has around 800,000 subscribers across multiple channels, compared to RT’s more than 3.3 million.

This could be down to content, while CGTN has relaxed considerably from its highly staid past, it lacks the type of slick appeal of RT, nor has it been so willing to host the type of conspiracy theorists who tend to do so well on YouTube.

Attention war

Whether or not its investment in China Daily and CGTN is paying off, Beijing clearly sees great value in promoting state media overseas, building on its effectiveness as a propaganda tool at home.

This effort has come under increasing scrutiny in recent years, and US and Australian lawmakers especially have said they are uncomfortable with the role Chinese state media plays in their countries.

China hawks such as Marco Rubio, chair of the Congressional Executive Commission on China (CECC), have long accused Beijing of using its influence around the world to stifle debate and promote its agenda.

“Chinese government foreign influence operations, which exist in free societies around the globe, are intended to censor critical discussion of China’s history and human rights record and to intimidate critics of its repressive policies,” Rubio said during a hearing on the “Long Arm of China” last year.

More recently, the US Department of Justice reportedly recommended CGTN and Xinhua be forced to register as foreign agents under an act designed to police lobbyists working for overseas governments. This followed similar restrictions placed on RT which caused the broadcaster to lose its congressional press credentials and were widely denounced by press freedom advocates.

Responding to question regarding the alleged move by the US government, Chinese Foreign Ministry Geng Shuang promoted the importance of free speech.

“Media serve as an import bridge and bond to enhance communications and understandings between people of different countries,” he said at a Beijing press conference, adding that countries “should perceive media’s role in promoting international exchange and cooperation in an open and inclusive spirit.”

Influence battle

While the hypocrisy of China complaining about restrictions on the press is self-evident, it’s important to remember that while US lawmakers complain about foreign media influence operations, Washington continues to run several of its own.

Beginning after World War II and ramping up during the Cold War, the US government invested billions of dollars in Voice of America, Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty, Radio Free Asia and related publications and broadcasters.

In 2018, the Broadcasting Board of Governors (BBG), which oversees those outlets, requested over $685 million in funds from Congress to cover costs for what it described as “one of the largest media organizations in the world.”

BBG subsidiaries broadcast in more than 60 languages to an audience of around 278 million people each week, with thousands of employees based in 50 news bureaus around the world.

In its statement to Congress, the bureau said its coverage is “particularly strong” in regions where “global actors that do not share American values are attempting to make further inroads.”

Both of the main broadcasters targeting China – RFA and VOA – are bound by their charters to be objective and are not subject to the same kinds of direct oversight exercised over Chinese state media, but this does not stop the countries which they target seeing them as malicious tools of US influence.

Following the 1989 Tiananmen Square massacre, funding for VOA broadcasting into China was ramped up, and in 1994 RFA was launched with an initial Chinese-language broadcast in order to “promote democracy and human rights” in China.

By their nature, BBG outlets tend to be pro-American in a broad sense, and often lean heavily on dissidents and critics in their coverage. Often this serves as a counter to domestic propaganda, which may feature little to no criticism of the government.

RFA in particular produces some excellent reporting from local journalists – often at great risk to themselves – out of Tibet and Xinjiang, areas of China from which most foreign journalists are locked out.

Since RFA and VOA started targeting China, Beijing has invested heavily in jamming radio signals from the two US-funded broadcasters, and state media has denounced them as tools of the CIA. Their websites and email newsletters are also heavily blocked and censored.

In one particularly ironic article, the Global Times lauded cuts to VOA, which it described as a “government-funded propaganda tool of the US,” even as it praised Chinese efforts to improve overseas broadcasting. Perhaps all involved need to look in the mirror.