Learn more about how genetic genealogy helped crack the NorCal rapist case on HLN’s “Very Scary People” airing Sunday, March 31 at 9 p.m. ET.

In a dizzying span of a few months, some of the nation’s most frustratingly unsolvable cold cases have suddenly been, well, solved.

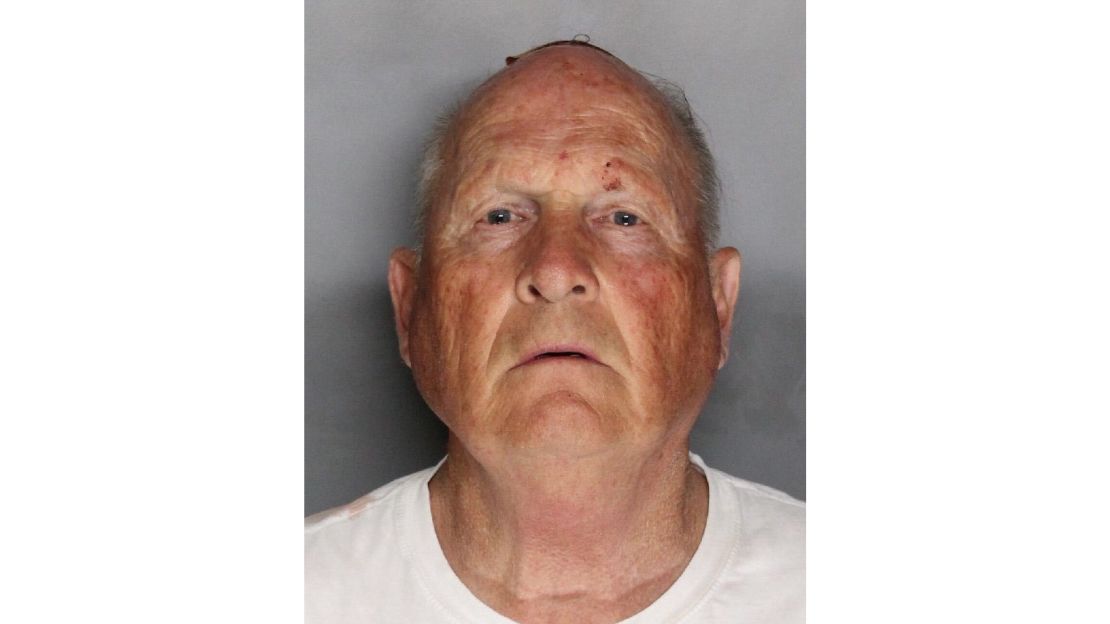

First was the arrest in April 2018 of a California man who police say is the notorious Golden State Killer.

Then came the arrest of a suspect in the 1986 killing of a 12-year-old girl in Washington state.

Soon authorities were charging a man for the 1992 sexual assault and killing of a 25-year-old schoolteacher in Lancaster, Pennsylvania, and another suspect for the 1988 rape and slaying of an 8-year-old girl in Indiana.

These breakthroughs have come thanks to DNA evidence and a new field of study known as genetic genealogy – pioneered by a group of passionate and largely unpaid hobbyists.

In the hands of law enforcement, the field is rapidly boosting detectives’ ability to crack cases that have stymied them for decades. And the willingness to use that ability has sharply increased since the Golden State Killer case was solved.

“Once the world sort of opened up to the possibility of using this methodology for suspect cases – and the world didn’t explode as a result – then the floodgates opened,” said Margaret Press, who has used genetic genealogy to identify the remains of dead people.

What is genetic genealogy?

It’s an emerging field that combines DNA evidence and traditional genealogy to find biological connections between people.

Over the past decade, companies like 23AndMe and Ancestry have encouraged people to spit into a tube and send it off for analysis. These companies analyze a customer’s DNA and send back information on their ethnic heritage, genetic health risks and family story – as well as a raw data file of their DNA.

The practice is increasingly popular and has become a big business. 23AndMe says it has over 5 million customers, while Ancestry says about 10 million people have used its services to have their DNA tested.

Genetic genealogists can use these raw data files to further learn about people’s family trees. But 23AndMe and Ancestry are private businesses, so there are some limitations and restrictions on what they can do.

That’s where a site called GEDMatch comes in.

What’s so special about GEDMatch?

GEDMatch is a free, open-source website where people can upload their DNA raw data files. Curtis Rogers and John Olson started GEDMatch in 2010 and it has grown consistently since.

Rogers, an 80-year-old professional guardian with a passion for visiting graveyards and sifting through old records, told CNN he started GEDMatch to create tools for genealogists like himself. The basic idea is that the site has certain tools that are better tailored for the work of genetic genealogists than the big genetic testing companies. Plus, it’s free.

GEDMatch takes in raw DNA files and compares them to the more than a million people who have already uploaded their name, email addresses and DNA data. After an analysis, GEDMatch produces a list of family relatives who have also opted in to its service, from immediate parents to fourth and fifth cousins, along with their contact information.

At this point, genetic genealogists get down to the nitty-gritty of their work – lots and lots of research. Genealogists take those relatives’ names and search through obituaries, birth certificates and other public documents to solve the puzzle that is building out an extended family tree.

This process allows genetic genealogists to help people locate long-lost family members, for example, or inform adopted children about their biological parents.

But what does that have to do with cold cases?

That same work is now being used to help detectives solve crimes.

Law enforcement already works plenty with DNA. Typically, investigators take DNA from a crime scene and compare it to a suspect’s DNA. Or they enter the crime scene DNA into a national database to see if there’s a match with a known criminal offender.

But if there’s no match, the perpetrator’s identity might remain unknown.

Now, though, investigators can take crime scene DNA and team up with genetics companies, such as Virginia-based Parabon NanoLabs, to turn that evidence into a raw data file and upload it to GEDMatch. The site then spits out a list of extended family members who are related to the perpetrator, allowing investigators to begin zeroing in on those who may have had close contact with the victim.

The use of these open databases thus expands the number of possible suspects to include people who have not previously committed a crime.

This type of detective work isn’t allowed on the big genetic testing sites. On its website, 23andMe openly states that it “chooses to use all practical legal and administrative resources to resist requests from law enforcement.” Similarly, Ancestry says it only releases customers’ information in response to a trial, grand jury or subpoena.

But by using GEDMatch, genetic genealogists work to build out an extended family tree to narrow down the list of possible suspects. Then investigators can do further detective work, such as surveillance, questioning, and testing of abandoned DNA samples – such as saliva on a napkin left in a suspect’s trash – to make an arrest.

Wasn’t the Golden State Killer case like that?

Exactly. For decades, investigators had searched for a man they suspected of a series of killings, rapes and assaults in the 1970s and 80s in California. But tests of crime scene DNA had not turned up any matches.

But in the past year, Paul Holes, an investigator with the Contra Costa County District Attorney’s Office, put the Golden State Killer’s DNA raw data into GEDMatch to narrow down the list of possible suspects.

Investigators pared down that list further by looking at people who were about the right age and living in the area during that period.

When one of the remaining possible suspects – Joseph James DeAngelo, 72 – went into a Hobby Lobby store in April 2018, investigators swabbed the handle of his car’s driver’s-side door, according to arrest and search warrants. They then tested that DNA sample against an existing crime scene DNA sample. He was a match for the killer, law enforcement officials said.

“This investigation lasted over 40 years, but with this course of DNA testing and matching, it took us only four months to get to the right pool of people,” Holes said.

Have other cases also been solved like this?

The use of DNA and genealogy in the Golden State Killer case garnered huge media attention and launched genetic genealogy into the mainstream.

Breakthroughs in other cold cases soon followed.

The 1986 killing of 12-year-old Michella Welch had long been a mystery for police in Tacoma, Washington. They had built a DNA profile of the suspect but had no matches in state or national databases. But after investigators began working with a genetic genealogist, they arrested Gary Hartman, 66, in June 2018.

Genetic genealogy also helped identify the man who police say abducted, raped and killed 8-year-old April Tinsley in Indiana in 1988. The mysterious killer left taunting messages over the years but still could not be identified.

Then in May, just weeks after the arrest in the Golden State Killer case, police hired Parabon NanoLabs and genetic genealogist CeCe Moore to work their expertise on the case. They narrowed the suspects down to two brothers, one of whom was 59-year-old John D. Miller.

DNA found on condoms in Miller’s trash matched that of the killer, and he confessed after police brought him in for questioning, a criminal affidavit states.

And in June, genetic genealogy helped solve the 1992 killing of schoolteacher Christy Mirack, 25, in Lancaster, Pennsylvania. For Lancaster County District Attorney Craig Stedman, the DNA work with Parabon NanoLabs was vital in leading investigators to Raymond Rowe, 49, now charged with her murder.

After comparing DNA found on a water bottle used by Rowe in May to samples taken from Mirack’s body in 1992, detectives learned the probability of the perpetrator being anyone other than Rowe was approximately one in 200 octillion, Stedman said.

Before the DNA testing, Rowe wasn’t a suspect, even though he had lived just four miles away from Mirack when she was killed.

Wait, so do police have access to people’s DNA?

Not quite. Curtis Rogers, GEDMatch’s founder, says GEDMatch provides matches to names and emails of relatives, but does not actually give out the raw DNA data.

Still, the ethics of allowing police any access to a site made up of people’s private DNA remains uncomfortable, he told CNN. He has worked to educate GEDMatch users that when they input their DNA they are opting in to its potential use in police investigations, a fact now prominently displayed in the site’s terms of service.

But if it helps solve old murders, he’s cautiously okay with it.

“Certainly catching the Golden State Killer, who makes Jack the Ripper look like a choir boy, is worthwhile,” he said. “But we do have an obligation to all of our people to give them the privacy that they want.”

CeCe Moore, the genetic genealogist who appears on PBS’ “Finding Your Roots,” says GEDMatch has been crucial to the field.

“GEDMatch is absolutely the key, and had (the founders) decided that they didn’t want law enforcement to use their database, we wouldn’t have been able to do this,” she told CNN.

What else can genetic genealogy be used for?

Margaret Press and Colleen Fitzpatrick, co-founders of the non-profit DNA Doe Project, use their genetic genealogy knowledge to identify the remains of unknown deceased people.

In April 2018, they identified the “Buckskin Girl,” a woman who was found strangled in Troy, Ohio in 1981 and whose identity had remained a mystery.

Press and Fitzpatrick are both PhDs – they call themselves a “Pair-o’-docs” (get it?) – and turned to genetic genealogy in their later years, like many of those in the field. In fact, the majority of people in genetic genealogy are hobbyists who volunteer their time, such as the “search angels” who help adopted children connect with their biological families.

There are a few professionals in the field, but even they often work pro bono on the side. This particular passion is already an emerging component of detective work and is only going to grow in the future.

“There is so much volunteerism in this community, it’s just incredible to be a part of it,” said Moore, who has personally helped solved several cold cases and says she was the first to call herself a professional genetic genealogist.

“It’s been the most amazing thing to watch this … field explode into an industry now, to see it from the beginning.”