Story highlights

The proportion of Americans at risk for foodborne illness is increasing

Better surveillance tools means more reports of foodborne illness outbreaks in the US

One child drank apple cider at a Connecticut farm, another a glass of juice during a road trip in Oregon; later, both were rushed to emergency rooms as they struggled for their lives. A middle-aged woman became sick more than a decade ago after enjoying a salad at a banquet hosted by a California hotel; her debilitating symptoms continue to this day.

A 17-year-old paid the ultimate price when he ate two hamburgers “with everything, to go” and died days later.

These are the stories behind the faces on the “Honor Wall” of Stop Foodborne Illness, the national nonprofit that represents and supports those who suffered a drastic consequence following the most ordinary act: eating.

It’s the “wakeup calls along the way” that prove to the industry “how imperative a strong food safety culture is,” said Mike Taylor, co-chairman of the nonprofit’s board and a former deputy commissioner for foods and veterinary medicine at the FDA.

Foodborne illness hits one in six Americans every year, the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention says, estimating that 48 million people get sick due to one or another of 31 pathogens. About 128,000 people end up in the hospital while 3,000 die annually.

Globally, almost 1 in 10 people are estimated to fall ill every year from eating contaminated food and 420 000 die as a result, according to the World Health Organization.

Preventing foodborne illness in the United States is the job of the US Department of Agriculture’s Food Safety and Inspection Service, which oversees the meat, poultry and processed egg supply, and the US Food and Drug Administration, responsible for domestic and imported foods.

With frequent news of outbreaks, which are investigated by the CDC, many people might wonder whether foodborne illness is on the rise – and whether safety measures across the nation adequately protect our food supply.

Is foodborne illness on the rise?

Matthew Wise, deputy branch chief for outbreak response at the CDC, said the agency usually gets “about 200 illness clusters” to evaluate each year. Wise described these clusters as “potential outbreaks.”

“Outbreaks are the very, very, very end of a long process,” he said. An outbreak investigation includes collecting evidence, confirming an illness-causing pathogen and tracing contacts; most of this work is performed by state health departments, though it is coordinated by the CDC.

Only about 15 of the 200 illness clusters investigated each year turn out to be actual outbreaks. As of Thursday, the CDC has declared 13 multistate outbreaks so far this year.

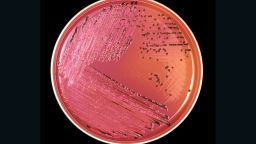

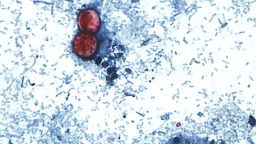

Preliminary data from the most recent CDC FoodNet report – which documents trends in foodborne illness outbreaks – hints that some forms may be on the rise: “The overall number of Campylobacter, Listeria, Salmonella, Shigella, Vibrio, and Yersinia infections diagnosed … increased 96% in 2017 compared with the 2014-2016 average.”

Catherine Donnelly, a professor of food science at the University of Vermont, said this increase may be partly due to improved tools both for detecting contamination in food and for outbreak surveillance, reporting and investigation.

“Surveillance has drastically improved, and state public health labs are linked to databases at CDC, allowing quick identification of patterns of illness and links to food products. As a result, we see more reports of foodborne illness,” Donnelly wrote in an email.

Her view is widely shared; Taylor agrees but said the question of whether foodborne illness is increasing is a “complicated” one.

“In some areas, like E. coli O157:H7, concerted strategies by government and industry have sharply reduced the number of illnesses associated with that pathogen,” Mike Taylor said. O157:H7, a particularly harsh strain of E. coli, causes bloody diarrhea and sometimes kidney failure or even death.

Still, reductions in salmonella, listeria and other key pathogens have not occurred, he said.

Reported outbreaks may have fewer cases today than in the past, Taylor said. The ability to detect outbreaks more rapidly, due to whole genome sequencing, also means the CDC can follow through and contain an outbreak more swiftly.

Donnelly notes that the proportion of Americans considered to be at risk for foodborne illness is also increasing – yet many people do not know or understand that they might be at risk, she said.

“Pregnant women, the elderly and persons with suppressed immune systems due to cancer treatment, diabetes, liver and kidney disease are just a few examples of conditions that increase the risk for foodborne illness,” Donnelly said. “Young children are also vulnerable to developing serious illness from foodborne disease.”

Outbreaks are also influenced by seasonal and environmental factors, she said.

“We do see more outbreaks of foodborne illness reported in the warmer summer months, where opportunities for food abuse arise [leaving foods unrefrigerated for periods of time, for instance],” she said. Flooding from storms has been associated with fresh produce outbreaks, while Vibrio illness linked to eating oysters may occur as a result of rising ocean temperatures.

The bottom line, Taylor said: “We have too much foodborne illness. It’s largely preventable. There’s a lot that has been done to reduce risk, and there’s a lot more that can be done.”

All of safety, though, begins with an understanding of our food system.

Evolving risks

The US food system is, in a word, global. “The reality is that there’s a ton of movement of food into and outside the US,” Wise said.

The volume of imports from all over the world contributes to the risk of foodborne illness because it is challenging to oversee all this diverse activity, Taylor said.

“Some 95% of the seafood consumed in the US is imported; 50% of the fresh fruit and about 25% of the vegetables are imported,” he said.

“People are tending to eat more produce and eat it in different forms, and those are good things, because we want people to eat more fresh produce, but when that happens, you’re likely to increase the risk,” Taylor said. This risk is due to the fact that fresh produce is “sold and prepared without any kill step,” such as cooking or canning, which can destroy illness-causing germs.

Wise also noted a new wave of foodborne illness due to sprouted products, such as chia seeds, as well as “commercially produced raw products that are popular.” Still, he said, the main question behind any outbreak – how did the food get contaminated? – is not a question the CDC can answer; it is the job of regulators and industry.

“Foods travel longer distances to get from farms to consumers, and pathogens can be introduced along the way,” Donnelly said. “There is wider geographic distribution of centrally produced foods, so when something goes wrong during production, the impacts are widespread.

“Many outbreaks linked to poultry, eggs and meat can be traced back to farms where intensive production practices can lead to [the] spread of highly virulent pathogens,” she said, while some are reflective of “poor food handling practices.”

But it’s not just one or some areas of the food system that are at issue, it’s the entire evolving system, Taylor said. “There are lots of different changes in the food system that affect risk over time, and so the food safety problem, therefore, evolves over time.”

A culture of safety

Among the most significant wakeup calls for the entire food industry was the 1993 E. coli outbreak from contaminated beef patties at Jack in the Box. Four children died while 178 others sustained permanent injury, including kidney and brain damage. Sometimes called the “9/11 for the meat industry,” this event is what inspired the formation of Stop Foodborne Illness, Taylor said.

“Since Jack in the Box, there’s just been enormous development of the understanding of the practices, the interventions that can work to reduce hazards,” Taylor said. For example, industry has focused on practices that can reduce pathogens on processing equipment and using microbial testing in food production systems to verify sanitation.

Many food companies have adopted “a best-practices continuous-improvement sort of philosophy,” he said. This comes down to “doing everything you can through the technology you’re using, the practices you’re using, the training that you’re using, the way in which you’re motivating employees. Are you doing everything you can so that every day, the right thing is happening?”

A culture of self-improvement is also what allows some companies to embrace the message delivered by Stop Foodborne Illness, which focuses on the vital importance of food safety.

“People actually die. People actually have their lives permanently changed with severe illnesses,” Taylor said. Leaders of companies use stories from the Honor Wall to motivate their employees and reinforce why it is so important for everyone to do the right thing every day to reduce the risk of illness from contaminated food.

“There’s no magic wand. It’s a day-in, day-out process,” Taylor said.

Industry may play the leading role, but the government must also perform at a high standard.

The politics of safety

The Food Safety Modernization Act became law in 2011.

The act “is still being implemented, but it basically codified this principle that everybody responsible for producing food should be doing what the best science says is appropriate to prevent hazards and reduce the risk of illness,” Taylor said. “So we’re moving in the right direction.”

Under the new requirements, state governments will be the frontline inspectors and overseers and supporters of food safety compliance for produce at the farm level, Taylor said. “They need resources to do that. There started to be resources available, but that funding is incomplete.”

Also under the act – and for the first time – the FDA will directly oversee the importers and evaluate whether they have in place the newly required foreign supplier certification program, Taylor explained. The program requires that importers know their foreign sources of supply (and their practices) and verify that suppliers are meeting US requirements.

The FDA’s greatest challenge, then, is that there are about as many overseas facilities registered to manufacture and sell food here as there are US-based facilities, Taylor said.

“Congress has gotten about halfway to what it said was needed to successfully implement” the act, Taylor said. Although it is still being phased in, the funding is incomplete.

“The commissioner of FDA, Scott Gottlieb, is supportive of FSMA,” Taylor said. “He’s continuing all those things that we’ve been doing during the previous administration and pushing forward on them. It’s not for lack of commitment and effort and FDA folks wanting to charge forward.

“Historically, food safety and nutrition have never been adequately funded at FDA,” Taylor said, based on his experience at the agency from the 1970s through 2016.

Donnelly said that “Beyond budget, there is a lack of trained food inspectors at FDA. Food companies complain that FDA’s approach to inspection is punitive, versus a more educational approach taken at [USDA], where on-site inspectors work with food processors to assure safe food production.”

Meanwhile, lawyers have replaced government scientists at the FDA in many instances, and so there is a lack of understanding of how certain foods are produced, she said.

“Without knowledge of production practices, it is difficult to offer guidance to processors to effectively manage risks. This is why education is key,” Donnelly said.

“As consumers demand more products that are fresh and locally produced, providing more hands-on education to producers to effectively manage risks can help produce safer foods,” she said.

Consumers also play a role in food safety well beyond their “demands” and purchases.

“This story is not complete if we don’t remind consumers they are part of the food system as well,” Taylor said.

The fifth pillar

The five pillars of foodborne illness prevention are farms; processing; transportation and storage; retail; and consumers, Taylor said: “It’s everybody’s problem and everybody’s solution at the end of the day.”

Donnelly noted that “the percentage of overall foodborne disease outbreaks linked to restaurant settings increased to 60% in 1998-2015, while outbreaks reported in the home dropped significantly to 8%.”

“Consumers with compromised immune systems need to reconsider their food choices,” she said. “As consumers age, their immune systems become less functional, increasing their risk. In a recent Listeria outbreak involving cantaloupe, the median age of persons who developed illness in the outbreak was 84.”

Wise said that whenever an outbreak occurs, the CDC repeatedly asks itself: “Have we reached a point to communicate?”

“If I go home and I think that there’s something I should tell to my mom or my wife about not eating, then that should be in the public domain at that point,” he said. “We do tend to communicate when we have identified a product with enough specificity that would allow someone to be able to take an action.”

Follow CNN Health on Facebook and Twitter

In each outbreak communication, the CDC informs the public about where sickness is occurring, the severity of illness, symptoms and product recall information, if any. It helps when people who believe that their own illness may be part of an outbreak talk to their doctors.

“People should know that there’s a lot of high tech, high-powered science going into figuring out how to do better at preventing foodborne illness,” Taylor said. “People should know that the system – government and industry – they’re not just sitting back.”