Story highlights

Symptoms of MGen are often similar to those of other sexually transmitted infections

If patients are given antibiotics for those diseases instead, it hastens move toward superbug status

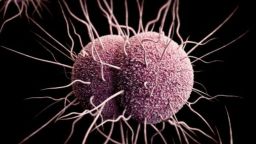

The British Association of Sexual Health and HIV has published new treatment guidelines in an attempt to prevent the sexually transmitted infection mycoplasma genitalium, also known as MGen or MG, from developing into a superbug.

Many experts believe that if the new guidelines aren’t followed, MGen – which is quickly becoming treatment-resistant – could become a superbug in five years, according to the British Association of Sexual Health and HIV.

Once it becomes resistant to antibiotics, MGen could leave up to 4,800 women infertile each year in the UK, according to the association.

“MG is rapidly becoming the new ‘superbug’: It’s already increasingly resistant to most of the antibiotics we use to treat chlamydia and changes its pattern of resistance during treatment, so it’s like trying to hit a moving target,” said Dr. Peter Greenhouse, the lead sexual health clinician at Weston General Hospital’s Weston Integrated Sexual Health Centre.

Information on global rates of MGen are hazy at best, according to Philippe Mayaud, professor of infectious diseases and reproductive health at the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine. However, he believes that about 3% of the population globally has it. In Europe, that number dips slightly to 1% to 2% of the population, the guidelines state.

The guidelines, published Wednesday, come only a few months after the first case of super-resistant gonorrhea was reported in the UK.

Like many sexually transmitted infections, MGen is often asymptomatic. When people do develop symptoms, they are often akin to those of other STIs, such as chlamydia and gonorrhea, according to the British Association of Sexual Health and HIV. For men, these symptoms include watery discharge from the penis and painful urination. For women, symptoms include irritation, bleeding after sex and painful urination.

Patients with MGen are often believed to have chlamydia because the symptoms are so similar, according to Dr. Mark Lawton, a consultant in sexual health and HIV and the clinical lead at the Liverpool Centre for Sexual Health. They are then given antibiotics for chlamydia instead of MGen, a miscalculation with potentiallyprofound effects.

“We are already seeing resistance to mycoplasma genitalium because we are using antibiotics that treat chlamydia very well but doesn’t treat mycoplasma very well,” Lawton said.

Giving antibiotics for chlamydia to patients with MGen builds the strength of MGen, making it much more resistant to antibiotics, Lawton says, a practice that is hastening its charge toward superbug status.

Among the guidelines are several measures that encourage the proper diagnoses of MGen. The measures include the testing of patients with symptoms and the consequent administration of the correct antibiotics, according to Lawton.

A commercial test for MGen has been available only in the past year, according to Mayaud. The availability of the test has, in effect, enabled the publication of these new guidelines, Lawton said.

Men with untreated MGen have shown a 5.5-fold higher risk of developing non-gonoccocal urethritis, or inflammation of the urethra, according to the British Association of Sexual Health and HIV. For women, the consequences are especially grave: They are 1.7 to 2.5 times more likely to developinflammation of the cervix, pelvic inflammatory disease – which can cause infertility – and preterm birth.

If MGen becomes a superbug and thus becomes harder to treat, it is also expected to increase rates of pelvic inflammatory disease, resulting in between 3,000 and 4,000 cases of female infertility each year in the UK, according to the British Association of Sexual Health and HIV. MGen may also be linked to an increased chance of HIV acquisition among females.

“If practices do not change and the tests are not used, MG has the potential to become a superbug within a decade, resistant to standard antibiotics. The greatest consequence of this is for the women who present with PID caused by MG, which would be very hard to treat, putting them at increased risk of infertility,” said Dr. Paddy Horner, a consultant senior lecturer at the University of Bristol.

Yet results of a British Association of Sexual Health and HIV survey of 125 health commissioners across the UK suggest that practices are unlikely to change. Only one in 10 says they intend to include spending provisions for MGen testing in their 2019-20 budgets, and 83% of respondents said they don’t routinely test for MGen in patients showing symptoms, with the majority citing a lack of funding as the main reason.

Follow CNN Health on Facebook and Twitter

“The new guidelines will be helpful, but unless and until we get funds so we can regularly test for it, we’ll be in the dark about which women with pelvic inflammatory disease have got it and about what their true risk of long term complications are,” Greenhouse said.

“Give us the tools, and we’ll get on with the job.”