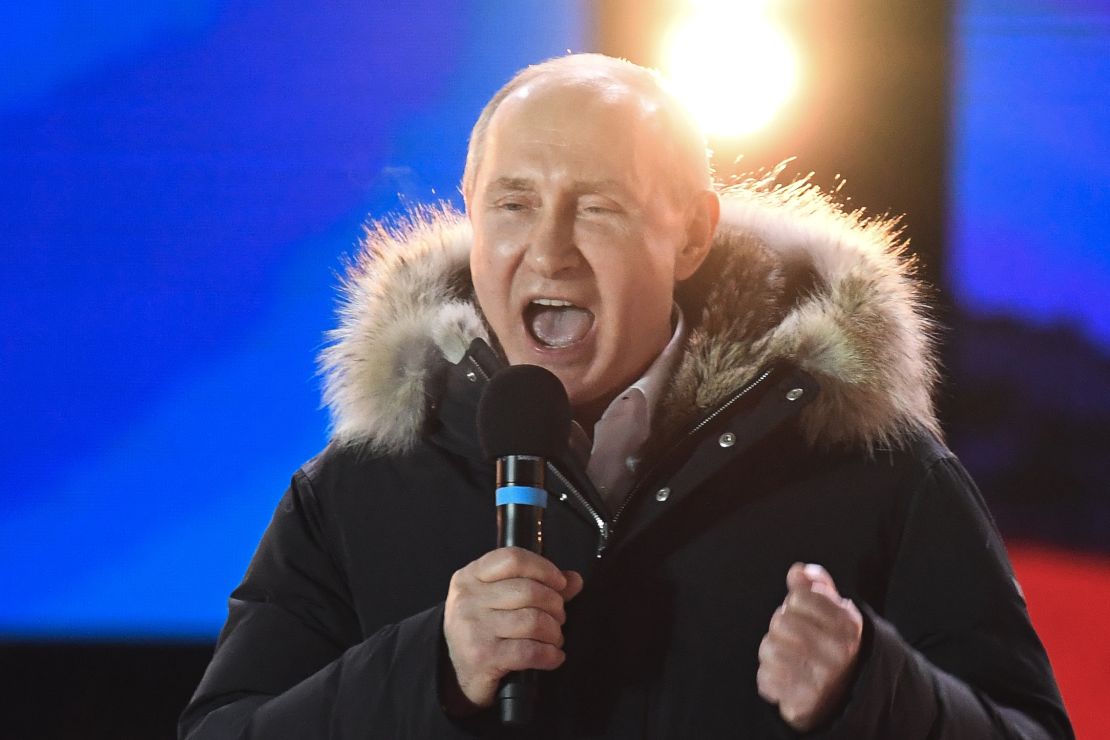

With almost all of the votes counted in Russia’s presidential election, the state-run Russia Public Opinion Research Center published an exit poll that showed Vladimir Putin with 76.6% of the vote.

While final results had yet to be released as Russians gathered in Moscow’s Manezhnaya Square for a Putin rally, it was clear that the Russian President was well ahead of the 63.6% he secured in the last election in 2012 – and on track to reach a widely reported goal of winning 70% of the votes cast.

That means several things: Putin can claim a clear mandate for his next six years in office. And the Kremlin can argue that Russia’s system of managed democracy represents the genuine will of the people.

That’s particularly key as Moscow escalates a confrontation with the West. Russia and the United Kingdom are in involved in a diplomatic feud over the poisoning of a Russian ex-spy, his daughter and a police officer in Britain earlier this month. And the Kremlin remains at odds with Washington after the United States hit Russia with new sanctions over its meddling in the 2016 presidential election.

Several factors explain the Kremlin’s ability to get out the vote.

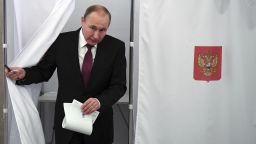

For weeks in advance of the election, the government funded an intense messaging campaign meant to get Russians to the ballot box. Mobile-phone subscribers received SMS notifications reminding them to vote. Billboards and public-service announcements also reminded eligible voters to go to the polls.

And on election day, it was clear that there were efforts to encourage turnout, although it was unclear if they were officially supported. At a polling station in central Moscow near the House of Government, the workplace of the Russian Prime Minister, employees of a construction firm told CNN that the company’s management provided transportation to the polls early Sunday.

International election monitors had not weighed in on the vote Sunday evening. Ella Pamfilova, Russia’s top election official, told the respected business news outlet RBC that there had been a “relatively small” number of reported violations during the vote.

But local election officials said they had confirmed an incident of ballot box stuffing in the Moscow suburb of Lyubertsy after studying video camera recordings, the state news agency TASS reported. And Golos, an independent watchdog group, said Sunday evening it has received over 2,700 reports of potential voting irregularities in Russia’s presidential election.

As of late Sunday, it was unclear whether the Kremlin had achieved the magic “70/70” formula: A 70% voter turnout, with Putin winning 70% of the votes.

Opposition leader Alexey Navalny, who had called for a boycott, declared a victory of sorts, saying: “If it had not been for our [independent] observers, there would have been 99% turnout. If it had not been for our observers , the turnout for Putin would have been 80%, and that would have given an opportunity to state that the ‘whole Russia stands for Putin.’”

“One should not think that the people are more silly than they are. Putin stated that our country is a democratic one, that our courts are fair, but he is lying. Sobchak is lying as well, that is why the people do not vote for her,” he said, referring to Ksenia Sobchak, who was projected to win 2.5% of the vote.

“One should honestly tell the people about poverty, the big gap in the income of the people,” added Navalny.

But 70 is also a number that may hang over Putin’s next six years.

Back in 2016, the respected business newspaper Vedomosti published a striking revelation: Between 2005 and 2015, the private sector’s share of the economy was cut in half In Russia. The report, based on a study by Russia’s Federal Anti-Monopoly Service, found that the government and state-controlled companies accounted for 70% of economic activity.

For some observers, the real question for Putin is whether he can now use his mandate to push for some program of economic reform.

Writing last year, Carnegie Moscow Center Senior Fellow Andrei Movchan speculated that the government would not loosen its grip on the economy after the elections.

“Judging by the current state of public opinion, future changes are likely to include stricter political control, further nationalization of private property, further shutting down the economic space, and new processes that make economic transactions in the country less sophisticated and more inefficient,” he said.