For more on the Ronald Reagan presidency and how it changed the game for the leaders who followed, watch CNN Films’ “The Reagan Show” on Monday, September 4, at 8 p.m. ET.

Since the day of his inauguration, critics of Donald Trump have been harshly evaluating his performances in a very particular area: Does he act presidential?

And it’s not just the critics: A recent Washington Post/ABC News poll says 70% of Americans believe Trump has acted in an “unpresidential” manner since taking office, with some respondents taking issue with the “inappropriate way he talks and acts.”

Why are those criteria so relevant? It’s a reassurance that presidents have the required gravitas to lead effectively, that “they can handle the job, they can take control in difficult situations,” presidential historian Julian Zelizer said. “Not ‘looking presidential’ is not seeming to have those skills.”

On the campaign trail, candidate Trump told a crowd of rally-goers in Connecticut that “presidential is easy.” He provided an interpretation of what that should look like: a sober tone, a solemn facial expression, controlled gesturing, dignified head-nods. “I’d have two teleprompters,” he told the crowd, “and I wouldn’t have to do this,” gesturing so the audience would stop cheering, “because there’d be very little applause, people would be bored.”

But Trump, a businessman and former reality show celebrity with no prior military or government experience, has so far struggled to adapt to the role of president, a role that wasn’t written with him in mind. That may be due to the fact that Trump is no actor. He’s a TV personality, who often appears to speak and tweet with no filter.

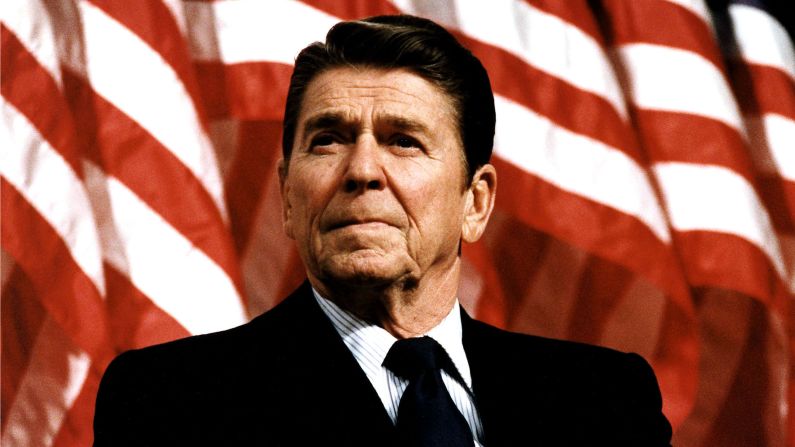

Granted, governing the United States is not the kind of job in which one can simply appear to be capable. But President Ronald Reagan once pointed out why a politician’s ability to mold himself to his role is so crucial to the job.

During his presidency, Reagan was asked whether he had learned anything as an actor that had been useful to him as a president. “There have been times in this office,” Reagan responded, “when I wondered how you could do the job if you hadn’t been an actor.”

Indeed, Zelizer said, acting skills served Reagan well throughout his two-term presidency, helping him broaden his appeal with the American public and build consensus in Congress. “The basic thing about Reagan’s acting and his public persona was always that he could sell conservatism to the public at a broad level,” Zelizer said.

“That was his selling point: to do it with a smile so conservatism didn’t look nasty or mean,” he added.

When Reagan did use his acting talents, he did so in a “methodical, contained and directed way,” a way “connected to his political objectives,” Zelizer said.

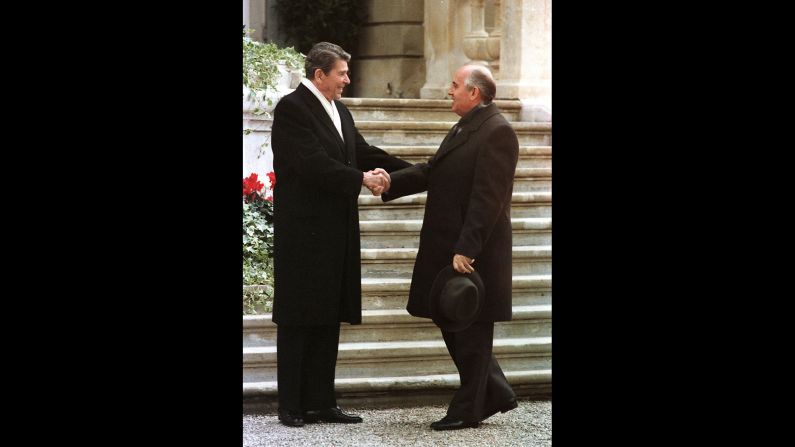

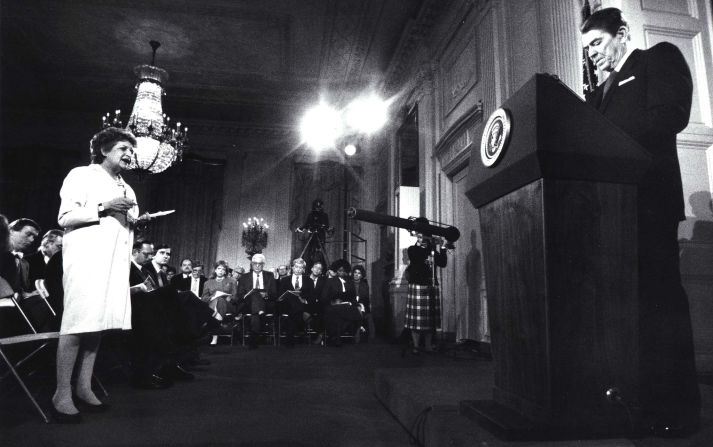

We saw this when he appealed directly to Americans in 1981, asking them to write letters to their elected representatives in support of advancing his tax reform bill, and in his ongoing dialogue with Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev, which culminated in a historic nuclear weapons-reduction treaty in 1987.

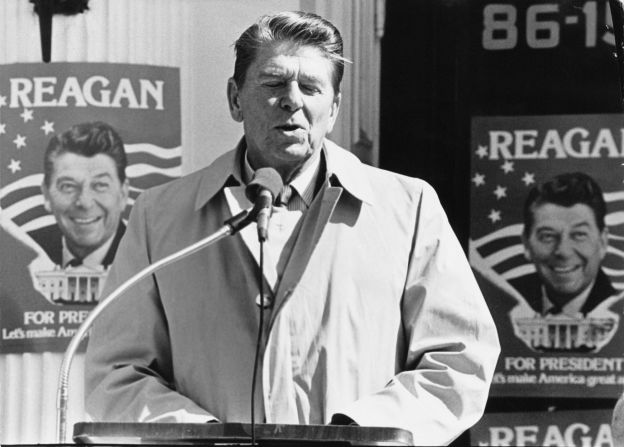

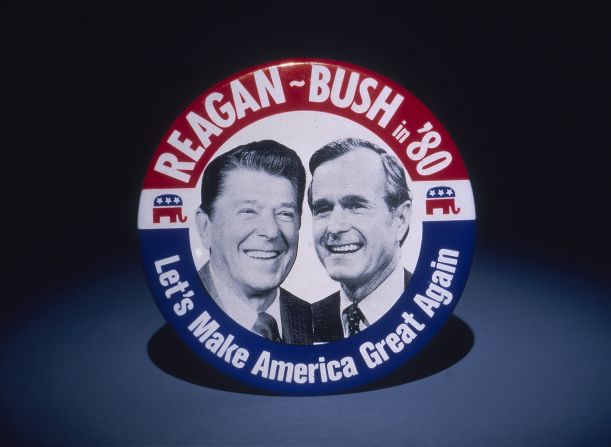

Of course, it’s important to note that while Reagan was a former Hollywood star, he also had a long political career. In fact, he served as governor of California for two terms before trying twice to obtain the GOP nomination for president, finally making it to the general election, in 1980, winning in a landslide.

“Reagan held positions that required an understanding of consensus and ability to compromise,” said presidential historian Tim Naftali, who argued that experience qualified Reagan to lead “much more than the fact that he was in some B-movies.”

Reagan could be relied upon to say exactly the right words to unify and uplift the country when tragedy struck, or when challenges were ahead. His historic speech following the explosion of the Challenger space shuttle in 1986 at once dealt with the tragic deaths of the crew and restated America’s commitment to pioneering advances in the field of space exploration.

Reagan’s delivery of these messages was incredibly powerful, a talent that earned him the moniker of “Great Communicator.” In his farewell address in 1989, he acknowledged it took more than acting chops to earn that nickname: “I wasn’t a great communicator, but I communicated great things,” he said. Most tellingly, he added that those things “didn’t spring full bloom from my brow.”

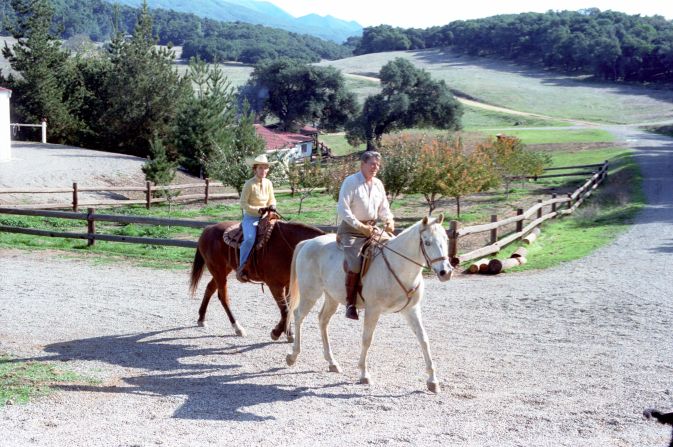

He credited America for inspiring him, but he probably also meant to nod to his PR apparatus – people like David Gergen, Michael Deaver and Peggy Noonan – responsible for crafting his scripts, curating his photo opportunities, coming up with so-called “lines of the day” to feed to reporters (lines that the President would repeat at every event to reinforce the desired narrative the administration wanted to convey), and producing more video footage of his presidency than the five prior administrations.

Acting requires empathy and the ability to take direction and receive feedback. Trump, who has yet to master that skill, often makes unilateral decisions about how he communicates, ignoring advice and often veering off script, making counterproductive statements.

Most recently, this happened in the aftermath of chaos in Charlottesville, Virginia, when Trump tacked on an ad-libbed “on many sides” to prepared remarks decrying the violence that unfolded among white supremacists, neo-Nazis and counterprotesters, one of whom was killed when a car plowed into a crowd. Trump also never abandoned the divisive rhetoric he used during the campaign season, and he hasn’t ceased to rally his base as if the campaign were still ongoing.

Trump’s penchant for saying outrageous things may appeal to his most extreme supporters, but it has the inverse effect of narrowing his support among moderates. This erosion was evident in recent NBC News/Marist polls, which found that after Charlottesville, Trump’s approval rating stood below 40% in Michigan, Pennsylvania and Wisconsin.

Trump is having “one of the most chaotic, turbulent and unpopular presidencies that we have seen,” and that’s mostly imputable to his public conduct, which has been “totally self-destructive,” and sometimes even put him in legal jeopardy, Zelizer said.

Trump’s public persona is the kind of “attention-grabbing act” that is “great on television,” Zelizer said, adding that Trump knows “how to make sure people are watching,” but doesn’t know “how to translate that into governing.”

Translating stage presence into governance is no easy feat, even for the most charismatic leaders. In conversation with a journalist, Reagan once spoke to how challenging that is, saying that in the role of president, “You not only have to get the part, you have to write the script.”

Like many other Republicans aspiring to seize Reagan’s mantle, Trump has deliberately tried to associate his image to that of the “Gipper” – the Notre Dame football legend whom Reagan famously portrayed on screen – and repeatedly poached from Reagan’s rhetorical arsenal.

His new economic plan, for example, introduced last month by budget director Mick Mulvaney, is called “MAGAnomics,” and was presented as “our version of Reaganomics.”

Trump even appropriated Reagan’s 1980 campaign slogan: “Let’s Make America Great Again.” But the one thing it seems he hasn’t learned from Reagan? How to act.