Story highlights

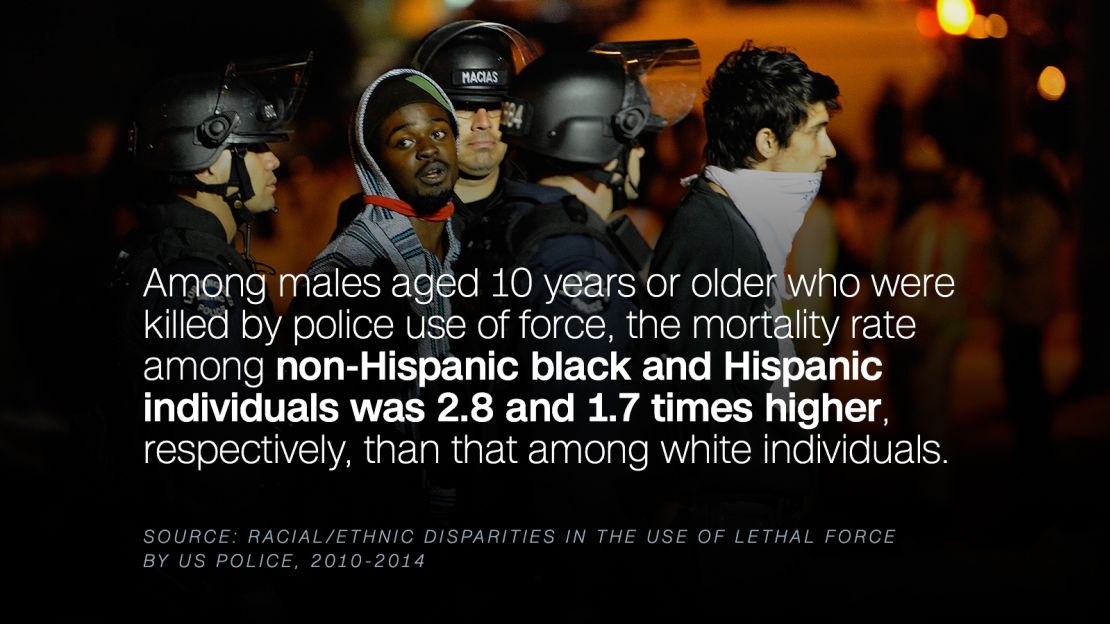

Black men are nearly three times as likely to die from police use of force, a study shows

Hispanic men are nearly twice as likely to die at the hands of police, according to the study

"It affirms that this disparity exists," says the study's author

Gregory Gunn. Alton Sterling. Philando Castile. Terence Crutcher. Those are just a few of the names of black men who were killed in high-profile police shootings in 2016.

Now, as the year comes to an end, a new study reveals disturbing data on how much of a racial disparity there may be in police use of force, or as researchers call it, “legal intervention.”

Black men are nearly three times as likely to be killed by legal intervention than white men, according to the study, which was published in the American Journal of Public Health on Tuesday. American Indians or Alaska Natives also are nearly three times as likely andHispanic men are nearly twice as likely, the study suggests.

“It affirms that this disparity exists,” said Dr. James Buehler, clinical professor of health management and policy at Drexel University in Philadelphia, who authored the study.

“My study is a reminder that there are, indeed, substantial disparities in the rates of legal intervention deaths, and that ongoing attention to the underlying reasons for this disparity is warranted,” he said.

Disparity disclosed in death certificates

Buehler analyzed national vital statistics and census data on legal intervention-related deaths, from 2010 to 2014, from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s Wide-Ranging Online Data for Epidemiological Research (WONDER) database system, which includes county-level death certificates.

The data showed 2,285 legal intervention deaths for that time period.

While the data did not provide details on the circumstances surrounding the legal intervention deaths, Buehler said that they allowed for him to take a close look at how many deaths involved black, Hispanic and white males, 10 years or older.

He found that, although white men accounted for the largest number of deaths, the number of deaths per million in each demographic population were 2.8 times higher among black men and 1.7 times higher among Hispanic men, respectively.

In other words, black and Hispanic men were 2.8 and 1.7 times more likely to be killed by police use of force than white men. White men accounted for more deaths only because they were of a larger population.

Additionally, Buehler found that American Indians or Alaska Natives accounted for fewer than 2% of legal intervention deaths but had a rate similar to that of blacks.

‘The psychological science on this is very clear’

The new study findings are a useful contribution to a growing body of research on racial disparities in lethal use of force by police, said Jack Glaser, a professor of public policy at the University of California, Berkeley, and author of the book “Suspect Race: Causes and Consequences of Racial Profiling.”

“It is very difficult, if at all possible, to generate an explanation for this pattern of results that does not include an influence of racial bias,” said Glaser, who was not involved in the new study.

“The psychological science on this is very clear. People, including police officers, hold strong implicit associations between blacks, and probably Hispanics, and weapons, crime and aggression,” he said, adding that this association is “supported by scores of studies.”

For instance, scientific evidence that people are more likely to shoot at a black target than at a white target was reviewed in a 2015 meta-analysis study, which was published in the Journal of Experimental Social Psychology.

In that study, researchers from the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign analyzed 42 studies and found that, compared to white targets, people are quicker to shoot armed black targets, slower to not shoot unarmed black targets, and more likely to have a liberal shooting threshold for black targets overall.

“Because these associations reside outside of conscious awareness and control, even well-meaning, consciously egalitarian officers are vulnerable to use more force on minority civilians,” Glaser said. “Police officers are only human, and in use-of-force situations they experience the kinds of normal emotions – fear, anger, anxiety – that set the stage for more spontaneous mental processes to be influential.”

While Glaser and other experts point to implicit racial bias as playing a role in this disparity, Buehler said that his findings also might be linked to poverty.

“Racial and ethnic disparities for legal intervention deaths reflect disparities in levels of poverty,” he said. “As a former public health official who has worked at federal, state and local levels, I am well aware of the fact that poverty is associated with an increased risk for multiple health problems, including injuries related to violence.”

A 2002 study published in the American Journal of Public Health found that legal intervention death rates for black men, on average, were 4.7 times higher than those of white men from 1979 to 1988, and 3.2 times higher from 1988 to 1997.

A 2015 data analysis conducted by researchers at the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health found that between 1960 and 2010, black men were always more than 2.5 times as likely to die due to legal intervention than white men.

In general, the rate in which police use force on blacks is 3.6 times as high as among whites, according to a separate think tank study released by the Center for Policing Equity in July (PDF).

However, “my study extends previous analyses by examining rates of legal intervention deaths among people who are Hispanic and American Indian (or) Alaska Native,” Buehler said.

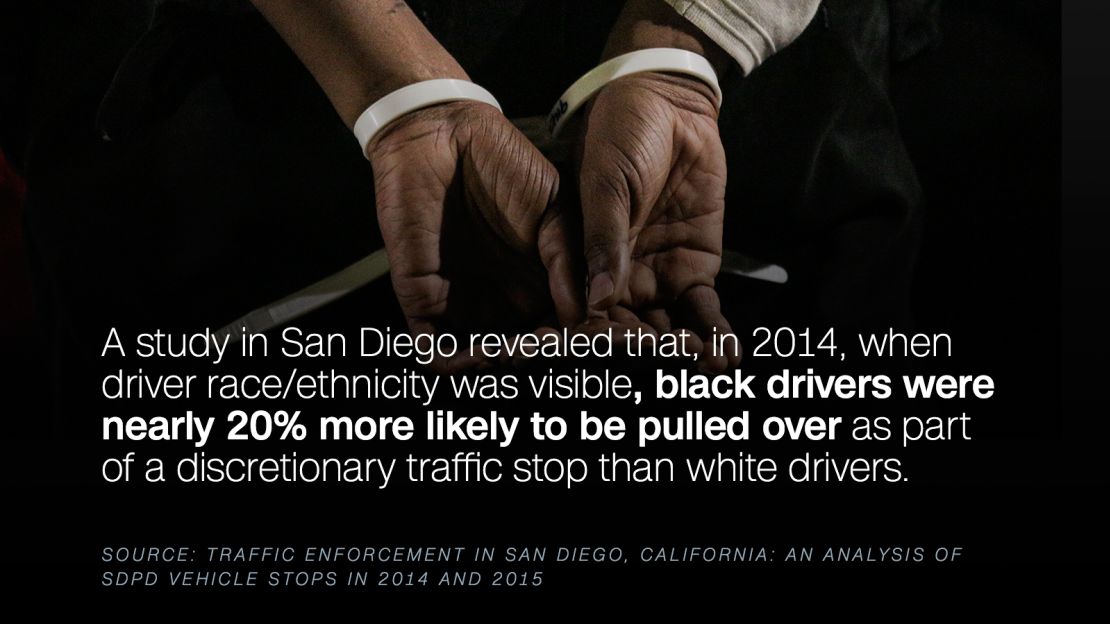

A study of traffic enforcement stops in San Diego, conducted by researchers at San Diego State University and published last month, found that, in 2014, when driver race/ethnicity was visible, black drivers were nearly 20% more likely to be the subject of a discretionary traffic stop than were white drivers (PDF).

Separate research, published in the journal Injury Prevention in July, suggested that, while racial minorities were more likely to be stopped by police, there were no racial differences in cases of injury or deaths due to use of force.

Buehler said that he felt motivated to conduct his study after a working paper, published by the National Bureau of Economic Research that same month, found no racial differences in the use of lethal force by police during very high-risk situations, such as aggravated assault.

Follow CNN Health on Facebook and Twitter

Roland Fryer, a professor of economics at Harvard University who authored the NBER paper, was unavailable to comment on Buehler’s study.

However, Buehler said that the difference between his study and the paper published in the NBER is that he measured death rates per total population size and the NBER report examined rates of the use of lethal force per numbers of “high-risk encounters,” such as an encounter that involved an aggravated assault against an officer rather than a routine traffic stop.

“Also, my study had a national focus; the NBER study examined the use of lethal force in one city: Houston,” he said. “There’s not a right way or a wrong way to approach the study of legal intervention deaths or the use of lethal force by police, but the two approaches address different questions and it’s critically important to understand that distinction.”