Editor’s Note: This story was originally published on CNN.com in 2013.

Story highlights

Ally Del Monte, 15, says she wanted to kill herself after being bullied by friends

"(Bullying) was normal because that's what I was used to," teen says

Bullying among friends can lead to difficulty forming new personal relationships

The taunts began in second grade, when Ally Del Monte started taking medication for a thyroid disorder and gained 60 pounds.

The boys at her elementary school in Westchester County, New York, banned her from the jungle gym because they said she would break it. The girls made fun of her large jackets and told her she was fat, ugly and weird.

She took everything they said to heart; it was a small school, and they were the only friends she knew. It’s what friendship was, she thought. Only years later, as the pattern persisted and grew more aggressive in middle school, did she begin to see that her friends were her bullies.

“To me, it was normal because that’s what I was used to,” the 15-year-old high school sophomore said.

“At first I didn’t consider it bullying because the people treating me like this were supposed to be my friends. That’s how I perceived myself because that’s what they were telling me.”

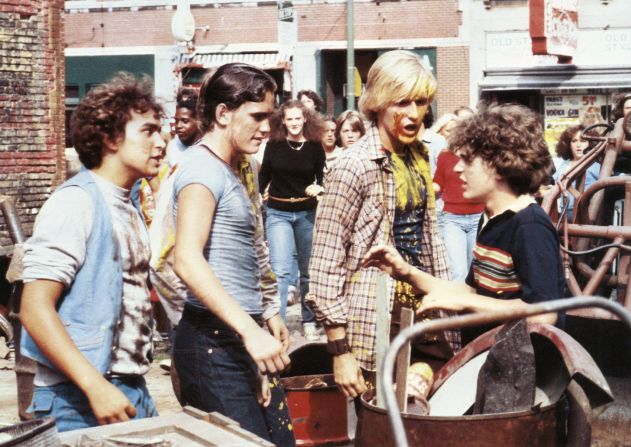

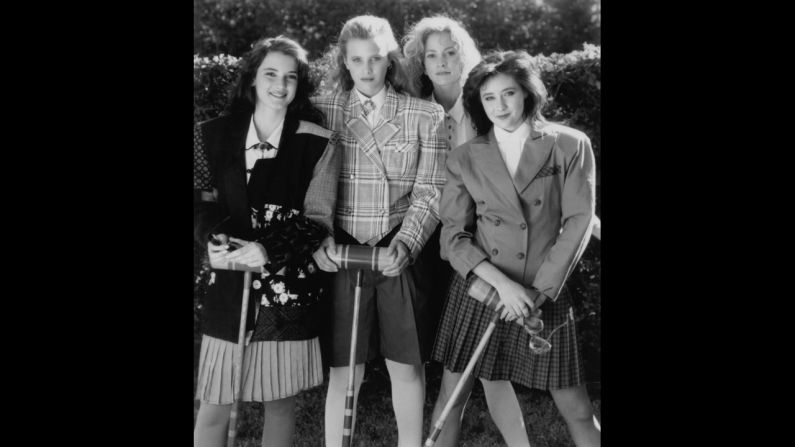

It’s a recurring theme in movies and pop culture, perhaps best epitomized in the 2004 film “Mean Girls.” Bullying among friends, also known as relational bullying, stems from a natural tendency to develop an identity based on your friends. Young people often join groups defined by who’s included or excluded, experts say, but it crosses the line when it becomes a sustained campaign to hurt someone who’s not currently “in.”

And while bullying awareness has risen in the past few years, bullying among friends remains hard to detect. It’s subtler than insults and punches between children who obviously don’t get along, said Lynn Bravewomon, coordinator of the Hayward Unified School District’s Safe and Inclusive Schools Program in California.

It can take the form of spreading rumors or belittling someone over what they wear. It can look like teasing over race, gender or how well they perform in school or sports. It can happen between the smiles and laughs of friendship, such as when Ally’s friends cracked jokes about what she wearing and followed it up with “just kidding.” Or, as Ally’s mother discovered, it can happen through social media, making it even harder for parents to detect if they don’t know to look for it.

It can also be more traumatic because relational bullying is a breach of trust by people who are supposed to be there for you – similar to how spousal or relationship abuse can lead to trust issues down the road.

“It’s a painful bullying dynamic, fed by people with various levels of closeness and friendship through silence or encouragement,” said Bravewomon, who teaches bullying prevention strategies to educators and students.

‘I couldn’t escape’

Ally experienced it most acutely after her family moved to New Milford, Connecticut, the summer before sixth grade. After a rough start, she became a cheerleader and fell in with the popular crowd. Friends regularly came over after school and on weekends for sleepovers. Her parents proudly watched her blossom, relieved that the move seemed like the right choice.

Then, in eighth grade, she had a falling out with a popular girl and once again found herself on the fringe of school social life. No one would talk to her in the hallways; they just pointed and laughed.

Eventually, the teasing got louder, meaner and turned physical. “They would shove me into lockers, trip me as I would walk by, and push me on the stairs,” Ally wrote in a CNN iReport.

Harassment continued outside of school through phone calls, often several in a week, sometimes twice in one night.

“They called me a fat pathetic b****, told me I was worthless, I was ugly, my mom should have aborted me, I should just kill myself, no one likes me, they all want me gone,” she said. “I felt hopeless. They could reach me everywhere I went. I couldn’t escape.”

Her mother, Wendy Del Monte, realized something was wrong when friends stopped coming over and Ally spent most of her time in her room. It all seemed to happen so fast; in less than two years, Ally went from being a popular cheerleader to having no friends at all.

But she didn’t want to be the overbearing parent, the mom who assumes everyone’s to blame except her own children. After all, meanness among friends isn’t the same as bullying, she told herself.

“You’re walking this tightrope, this fine line between trying to protect your children without protecting them so much that they’re not able to reach their full potential or learn from their mistakes,” Del Monte recalled.

She did everything she thought she was supposed to do. She contacted Ally’s school, put her in counseling and got her on medication, per the doctor’s recommendation. But she didn’t know that her daughter had turned to cutting and burning herself as a way to release her anguish.

She also didn’t know Ally had an account on the blogging tool Tumblr until she found her daughter balled up and sobbing on her bed, trying to open a bottle of her father’s blood pressure medication. She was planning to attempt a drug overdose. That’s when she saw dozens of messages on Ally’s phone, telling her to kill herself.

“She finally said to me, ‘I’m really sad. I don’t know how to handle all of this,’ ” Del Monte said. “It’s like your entire world stops and pivots.

“I’ve tried to figure out the words for what that moment is like, but it’s just the most awful thing you can think of when the person you love so much and brought into this world tells you, ‘I want to leave this world because it’s not the right place for me.’ “

Del Monte brought her daughter to a crisis center, and the family tried to help Ally become whole again. When she wasn’t at school, she was with her family or talking to a counselor. She slept on an air mattress in her parents’ room for several months. She started a personal blog, Loser Gurl, to work through her feelings and help others.

Things eventually got better, “but it wasn’t instant,” Ally said.

“I sometimes still felt alone, hopeless, worthless, disgusting and pathetic. It didn’t go away all at once,” she wrote in her iReport. “But slowly, it did go away.

“I made it to high school. I survived.”

Understanding what makes some adolescents vulnerable

This kind of bullying – between people who even recently appeared to be in a healthy, normal friendship – isn’t the most common. In a recent study, 30% of 18-year-olds said their friends had bullied them at least once, according to Elizabeth Englander, a psychology professor and founder and director of the Massachusetts Aggression Reduction Center at Bridgewater State University.

But it’s important because it reflects the extent to which children value peer relationships and understand what it means to be a friend.

“Social rules are the most powerful shaper of social behavior, and society cannot function without social norms. It’s important to utilize them as best you can so that people are as good and kind and helpful to each other as possible,” she said. “If we don’t impress that friendship relationships carry obligations, we’re giving up some of our leverage to get people to behave themselves.”

Englander’s study, which is still in progress, also looked at why some adolescents are more vulnerable than others to being bullied by friends. Common factors included difficulty being active in the school community, anxiety, depression and trouble maintaining friendships.

“By understanding what makes kids vulnerable, it gives you a map for how you can help these kids cope in a more resilient way,” she said. “You can’t affect if parents get divorced, but you can affect the support systems we provide to kids.”

As with any form of bullying, prevention and intervention comes from fostering respect and empathy for others. (It’s not just a problem for children. Adults also tend to define themselves by their differences, too, experts said.)

The challenge facing both groups is simple: Can we honor and respect our own values – “without defining them by hating others”?Bravewomon asked. In other words, if owning expensive sneakers or being fourth-generation Americans is what binds a group of friends, can they learn to live with others unlike them?

“Schools need to wholeheartedly respect and value belief systems that all families teach,” she said.“Where it runs amok at school is when students use hate-based behavior because of a personal belief system.”

So what can educators and parents do if they can’t necessarily even see bullying cloaked in the highs and lows of friendships?

The first step is modeling positive behavior to build a schoolwide expectation of kindness, respect and empathy and cultivate an environment where everyone feels connected, said Chen Kong-Wick, violence prevention program manager for the Oakland Unified School District in California.

“We spend a lot of time teaching students academic skill sets, but we don’t teach expected positive behavior,” she said. “It’s harder to gossip, bully or name-call someone if you have a relationship with them.”

New Milford Public Schools, where Ally goes to high school, tries to promote an environment of respect by focusing on a different “character attribute” each month, Superintendent JeanAnn C. Paddyfote said.

In October, when the focus is on responsibility, students have taken turns on the public announcement system sharing what the attribute means to them. It could be handing in homework on time or, in the context of bullying, telling a teacher when they see a someone being mistreated firsthand or on social media.

In the digital age, teachers and parents need help from students to spot cyberbullying, Paddyfote said.

“Anyone who wants to engage in bullying or mean-spirited behavior knows how to do it so no one catches them,” said Paddyfote, who declined to comment specifically on Ally’s case, citing district policy.

“A good friend – or person – will have the courage to go to a guidance counselor and let us know when something’s happening before it’s too late.”

Creating a ‘success story’

Families play a vital role, too, in modeling empathy, respect and kindness – a lesson the Del Monte family has absorbed in a variety of ways.

These days, Wendy Del Monte monitors every aspect of her children’s social media activity. She has all their passwords so she can check them when she wants. Her son and daughter can’t bring their smartphones into their bedrooms at night; they charge in the family room.

She even helps Ally run her blog, Loser Gurl. Del Monte tried to discourage her at first, fearing it would become yet another platform through which people would attack Ally. And, while her first post about struggling with her weight drew some negative comments, they were outnumbered by others thanking her for sharing.

Through her blog and social media, she estimates that she has connected directly with more than 60 victims of bullying to offer a sympathetic ear and encouraging words. She has friendships – fewer but healthier, many of them online.

Follow CNN Health on Facebook and Twitter

Ally’s goal is to become a motivational speaker so she can help others struggling with the effects of bullying. She wants them to know that their value resides well beyond the social boundaries of high school cliques.

“There’s not really a success story for anyone who’s been bullied. I feel like people need to know that someone got through it without having to kill themselves,” she said.

“So many people with suicidal thoughts feel like they’re alone or no one understands what they’re going through. I never want anyone to feel like that again.”