Editor’s Note: Kelly Wallace is CNN’s digital correspondent and editor-at-large covering family, career and life. Read her other columns and follow her reports at CNN Parents and on Twitter @kellywallacetv.

Story highlights

BMI screenings did not have an impact on obesity in New York City schools, according to study

Screenings can actually cause more harm than good, activists say

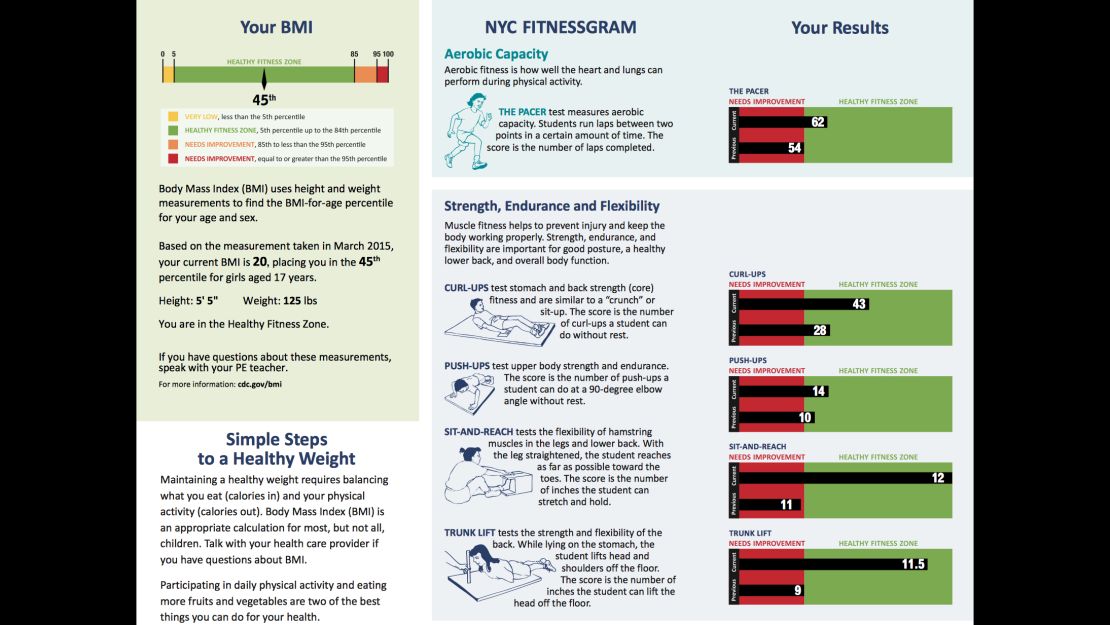

I remember opening the envelope holding my daughters’ report cards from their New York City elementary school a few years ago and stumbling upon a fitness report. The so-called “FITNESSGRAM” tallied my daughters’ height, weight and body mass index, or BMI. I had no idea we would get such a report or that my daughters were weighed at some point during the school year to come up with the measurements.

What I remember thinking back then was that I had hoped my children wouldn’t see the reports. They are only 8 and 9 now, and were even younger when we received those first letters. I wondered why they needed to have any sense of their weight or BMI at such a young age.

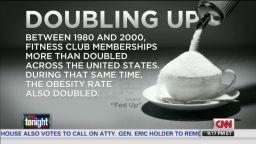

Twenty-one states, including New York, require these BMI screenings or other weight-related assessment at schools, according to the State of Obesity annual report. But now a new study is raising questions on whether such screenings of students even work.

Researchers obtained more than 3.5 million BMI reports for New York City public school students from 2007 to 2012, according to the study published this week in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. They compared the students who were classified as overweight, but near the BMI cutoff that would put them in a healthy weight category, with those students who just narrowly missed being designated as overweight.

What they found when they looked at the reports for the following academic year was that being labeled “overweight” or “obese” had no effects on the students.

“A year later, if you’re looking at the girls, the ones that got the overweight notice are no trimmer, no less likely to be overweight, or … no less likely to be obese,” said Amy Ellen Schwartz, one of the study’s co-authors, and a professor of public affairs at the Maxwell School of Citizenship and Public Affairs at Syracuse University. Similar findings were found for boys, she said.

“I think that the hope was that by letting parents know, ‘Hey, your kid is overweight, your kid is obese,’ they would say, ‘Wow, I didn’t know that’ and take action, or the kid would, and we didn’t see that,” said Schwartz, who is also a senior research associate for the Center for Policy Research at Syracuse’s Maxwell School.

In a follow-up study, Schwartz said she and her colleagues plan to explore whether the fact that there was no change was because parents never saw the fitness reports. They plan to study whether email or “snail mail” messages might be a more effective way to get a message to parents.

“A kindergartener? I don’t know, maybe you know, you’ve got to go through the whole backpack … What happens if you’re 12 and you pull it out” and you don’t like what it says, she said. “Then what you do is crumble it up in a ball and you throw it out.”

In response to the study’s findings, a representative for the New York City public schools said the study does not reflect recent changes in the fitness reports.

Schools no longer use the distinctions of “overweight” or “obese” and now use “healthy fitness zone” and also “needs improvement” for students with higher BMIs, according to Toya Holness, deputy press secretary for the New York City Department of Education.

“These assessments, which include measures of health related fitness in addition to height and weight, are shared with students and their families to spark conversations about eating habits and levels of physical activity needed for good health,” she said.

More harm than good?

Beyond questions about whether these assessments work, there are concerns that the reports can cause more harm than good.

Claire Mysko, chief executive officer for the National Eating Disorders Association, said she and her colleagues hear every day via their help line or through other outreach that these screenings were a spark around disordered eating for their children.

“We’re not making a causal relationship in that BMI tests cause eating disorders because these are very, very complex illnesses … but these tests can be trigger moments,” said Mysko. “So if someone is vulnerable and in a vulnerable place (and is) being weighed at school or being measured in whatever way … these are things that can be very triggering for those who are at risk.”

Over the past few years, activists concerned about the dangers of BMI screenings have lobbied federal lawmakers and officials, pushing for some guidance to provide schools about the effectiveness and safety of the assessments.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention has said that “little is known” about the impact of BMI measurement programs, including the effect on attitudes and behaviors of children and their families. “As a result, no consensus exists on the utility of BMI screening for young people,” it says.

However, the CDC does note that groups such as the Institute of Medicine recommend BMI screenings be conducted at schools. Also, the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force, for its part, found adequate evidence that BMI was an acceptable measure for identifying children and adolescents with excess weight and recommends that primary care clinicians screen children aged 6 years and older for obesity, according to a spokesperson. Those recommendations do not speak to school-based screenings. Back in 2013, Massachusetts announced it would no longer be sending BMI report cards to students.

BMI screenings don’t work “because they’re shaming kids and families,” said child and family psychotherapist Ava Parnass, the author of “Hungry Feelings not Hungry Tummy.” “So what does shame do? Shame makes you eat more but in a hidden secret way, and shame also makes kids and parents feel even more badly about themselves so they’ll eat even more.”

Ultimately, if you don’t teach people in a positive way what they can do differently and what feelings they might be medicating through food, nothing will change, said Parnass, who also writes on her blog about moments such as when a child says, “Mommy, I feel fat.”

“What does the BMI do? It’s a report card that doesn’t say, ‘Hey, here’s what you can do differently,’ There’s no teaching of new skills,” she said.

Proponents of screenings say they are a way to help educate children and their families on how to live a healthy lifestyle and reduce childhood obesity.

“It’s not like a big report card with a big letter ‘F’ in red” but is “a different way to frame a larger conversation about health overall,” said Holness, the New York City public schools spokeswoman. “I don’t think at all if you look at the assessment that it’s meant to be a shaming tool in any way. I think it’s not presented that way.”

Parents’ views

Curious to know what parents across the board think about these BMI screenings, i sent an email query to more than 120 women and men, mostly bloggers and writers. I received a handful of responses – all voicing opposition to these assessments.

Children’s television host Miss Lori wrote, “In defense of all the big boned kids out there who, like me as a child, never fit into the suggested markers for health and fitness but can run, dance, dribble circles around more than half of their classmates, I say kick the numbers to the curb.”

The mother of three, social media specialist and Babble.com contributor said BMI, weight and percentiles don’t always account for the physical changes girls and boys experience as they hit puberty, don’t consider the children’s socio-emotional awareness and sensitivity, and “fly in the face” of the development of a positive body image.

“Stop weighing kids down and start lifting them up,” she said.

Before Ellen Williams was a blogger and writer, and co-founder of Sisterhood of the Sensible Moms, she received her medical degree and focused on preventive medicine.

Her children, ages 15 and 17, attend public school in Maryland and have received the BMI screenings. “The thing with screening tools is that they’re great for gathering population data, but they are useless to individuals unless strategies are implemented to help those found at risk,” she said. “So these kids are being told they are overweight without being taught how to improve the situation with nutrition and exercise.”

Identifying the problem is only the first step, she said. “It’s action that puts prevention in preventive care. It is a disservice to do these screenings without treatments in place.”

Kelli Arena, who’s three kids did not have BMI screenings in Houston, said she sees solid arguments for and against the assessment, but the only one that truly matters to her is whether it will work.

“In my opinion, it won’t,” said Arena, a journalist and executive director of the Global Center for Journalism and Democracy at Sam Houston State University. “Let’s face it. Those parents know their kids are not at a healthy weight, and seeing a BMI on a report card won’t change habits. Will it lead to more exercise, or healthier eating at home? I’d bet money on ‘no.’ If they are not listening to their doctors or paying attention to news reports about the obesity epidemic, why would a number on a report card matter?”

Laura Beyer, a mother of two grown children, also thinks BMI screenings won’t work.

“The only way to fight obesity is to address unhealthy habits in that child’s home,” said Beyer, who blogs for her local newspaper in West Allis, Wisconsin. “I can guarantee that parents whose children’s BMI falls into the category of obesity aren’t losing sleep over it in the first place.”

Follow CNN Health on Facebook and Twitter

Something needs to be done to tackle childhood obesity, but BMI screening, while well-intentioned, might not be the answer, parents and advocates for eating disorder awareness say.

“Everyone (says) ‘Oh obesity, obesity, we have to do something about the obesity epidemic,’ and so it’s like throwing spaghetti at a wall without any evidence behind it and then you see that these programs are actually backfiring,” said Mysko, with the National Eating Disorders Association.

“We have to be very careful that in our efforts to combat one so-called epidemic that we’re not adding fuel to the fire of another one.”

Do you think BMI screenings should be conducted in schools? Share your thoughts with Kelly Wallace on Twitter @kellywallacetv.

Editor’s note: A previous version of this story incorrectly characterized the position of the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force on the issue of BMI screening for students. It has been corrected above.