Editor’s Note: David G. Allan is the editorial director for CNN Travel, Style, Science and Wellness. This essay is part of a column called The Wisdom Project, to which you can subscribe here.

Every year at my parochial elementary school, the students were conscripted into selling chocolate bars as a fundraiser, not unlike how Girl Scouts sell cookies to raise money for their local troop.

The sales were meant to subsidize my cash-strapped school and fund basic supplies, books and the occasional field trip. But the sales incentive for myself and other students was not supporting education. It was the prizes.

Brochures displaying shiny toys and games were handed out at an annual, “Music Man”-esque assembly led by a representative of the fundraising company. If you sold, say, 50 bars, you picked from the first tier of prizes, such as a simple bike lock. Sell 100 bars and you had a nicer set of prizes from which to choose. And so on, until the top layer with the big prizes, such as a bike.

The motivating interests of students, the school and our patrons were different, but aligned. The school got its money, the public got its chocolate, and we got our toys.

This scheme works with little kids too. Stickers and prizes for good behavior, potty training, what have you. They may be motivated by the reward, but they doubly benefit from establishing a new habit.

I needed to start a new habit and thought I’d try to reward myself with prizes if I was successful.

The real incentive versus the virtuous wrong one

After years of calorie counting, of exercise regimes, of flirting with diets and food restrictions, I had an epiphany three years ago that being more fit was simply not enough of a motivation for me to make a change.

I thought I wanted to be trim so badly that I could stick to some diet and exercise plan to get there, but it turns out I want ice cream, bagels and movie popcorn more than I wanted to shed the extra 30 pounds I was carrying.

Then I remembered the chocolate bar scheme. What do I want more than a general desire to lose weight (and also more than cheesecake)? Prizes! Gifts for me that I won’t simply buy for myself, and that no one else even knows I want.

The next part was the most fun. In the days leading up to New Year’s, I made a list of things I really want, ranging from a bottle of the Belgian beer Chimay to a Brompton folding bike, with a lot of nostalgic childhood toys and ski gear in between. I broke them down (by cost) into six levels that corresponded with weight ranges. I made a PowerPoint brochure so I could see them all together.

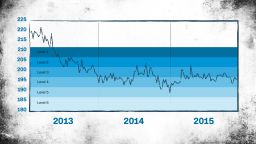

I decided that if I weighed between 212 and 208 pounds by the end of the year, I earned a Level 1 prize; between 207 and 203 pounds, I earned Level 2; and so on. Level 6 was the highest healthy weight loss I could sustain. There, along with the folding bike, awaited a fully kitted Millennium Falcon toy I had pined for as a child.

Unlike the chocolate bar prizes of my youth, in which the organizers had to guess at a wide range of prizes to appeal to different tastes and desires, every item on my personal chart was something I really wanted.

Finally, I marked up a piece of graph paper that labeled the levels across 52 columns for a weekly weigh-in over the year. The whole process was creative and fun.

The inverted New Year’s resolution

After enough times on the scale, I became very attuned to fluctuations of my weight. I understood exactly how a 3-mile run, or conversely, an almond croissant, would affect the number. Recent research has shown that when it comes to diets, one size does not fit all anyway.

There was no need to restrict any foods or track calories. I just had to hone this gestalt awareness of my actions. I never stopped consuming doughnuts, pizza and beer, I just got increasingly proficient at making it all come out in the wash.

I also discovered, a few months in, that a year is a long time to wait, so I tweaked the system. I added another incentive layer to help week to week: earning trips to the movies and new books. If I found myself tempted to have a peanut butter-filled cupcake that someone nicely (cruelly?) brought into the office to share, I would turn my attention to the book or movie I could buy or see at the end of the week.

This phenomenon – of incentivizing a good behavior with a reward – is known as the “Happy Meal effect” by researchers who have studied how money can effectively incentivize people to quit smoking, lose weight and make other behavior changes. In one study, published in the Journal of Experimental Psychology: Applied, people were simply offered the chance to win gift cards in return for eating only half of their lunch (a “high-end bacon-avocado sandwich”). As many as 89% were happy to make the trade.

The main incentive for me was still the big, end-of-year Happy Meal prize. And this was another thing I realized about the effectiveness of this experiment: Unlike most New Year’s resolutions – the majority of which are abandoned by summer, and almost all of which (92%) don’t last through December – my year-end goal kept me more committed as the year progressed, not less. I didn’t starve myself at Christmastime for my final December 31 weigh-in, but I didn’t binge on peppermint bark chocolate and eggnog either.

At the end of the first year, I weighed 25 pounds less than I did at the beginning, bringing me in at Level 4. I bought a beloved vintage toy from my youth on eBay: an 8-track cassette-fueled trivia “robot” called 2-XL. It was my “Rosebud.”

Incentivizing maintenance

Having lost the majority of what I wanted to lose, I needed my system to reward keeping it off. By not making the goal the number of pounds shed, but rather weight range, I began the second year already at Level 4. Even if I just maintained this new, lower weight at the end of year two, I would earn a similar prize.

And so, in my second year, I fluctuated a bit and ended the next December five pounds lighter at Level 5. I bought myself an iPad.

To help combat the fluctuations of the previous year, for this, my third, I decided to give myself two additional prizes: one mid-year, to keep me focused in the summer, and another that rewarded the number of weeks I remained below a new weight I’m trying to maintain. It worked. The number on the scale has been more consistent, thanks in part to my mid-year Level 4 prize of a high-end coffee grinder.

And as I approach the end of the third year, I’m doing OK. Level 5 might be a stretch, but if I didn’t have my incentive program in place, I’d be dunking a cruller in a mocha latte while writing about something else right now.

The point of sharing this system isn’t for you to replicate my experiment. It may not work for you, especially if you simply buy things you want. The point is to get you to think about applying the general principle of incentivizing a behavior in which the intrinsic reward is not enough of a motivation. Find a motivator, and even if it’s different from your intended goal, it can help you reach it.

If you hate to exercise, maybe you can find ways to make it so much fun you don’t think of it as a workout, like taking a fitness class with friends or joining a sport so that socializing is the real incentive. If you’re trying to quit a bad habit, maybe you reward yourself with other, less harmful or addicting indulgences after increasingly longer abstentions.

There’s always something you want, right? Can you figure out how to give that to yourself to incentivize a behavior you can’t otherwise master for its own sake? If so, you’ll indubitably find the experience, uh, rewarding.