Editor’s Note: Issac Bailey has been a journalist in South Carolina for the past two decades and was most recently the primary columnist for The Sun News in Myrtle Beach. He was a 2014 Harvard University Nieman Fellow. The views expressed are his own.

Story highlights

Issac Bailey: Too often police get away with wrongdoing, often because their fellow officers don't step forward

Officers are almost never held criminally accountable for the wrong they commit in uniform, he says

In Chicago, they watched as 17-year-old Laquan McDonald was executed in the middle of the street and did nothing. They felt no compunction to come forward to assure that justice be done. They used official reports to cover up what happened.

In Myrtle Beach, South Carolina, they paralyzed a man while shooting at him several times in his small apartment, claiming they fired on him because he shot first. They said they knocked on his door and identified themselves. But after an independent prosecutor found that the man, suspected of selling small amounts of marijuana, had not fired a shot, they changed their story, insisting that he pointed a gun at them, something the victim disputes. A video of the officers entering the apartment doesn’t show them knocking before ramming the man’s door down; an eyewitness said they didn’t identify themselves first.

After that evidence emerged, the independent prosecutor and the local solicitor, who filed more charges against the paralyzed man based on the word of the cops who had wrongly said the man shot at them, were not moved enough to call a press conference to explain the discrepancies – even though they had spoken publicly months earlier to claim the officers did nothing wrong and the man was a bad guy.

In Delaware, a man quickly complied with police officers who caught up to him. As he went to his hands and knees as instructed, one of the officers kicked him in the face, breaking his jaw, and it was caught on clear video. The initial grand jury failed to indict, and even after the officer was subsequently charged, a jury decided not to convict.

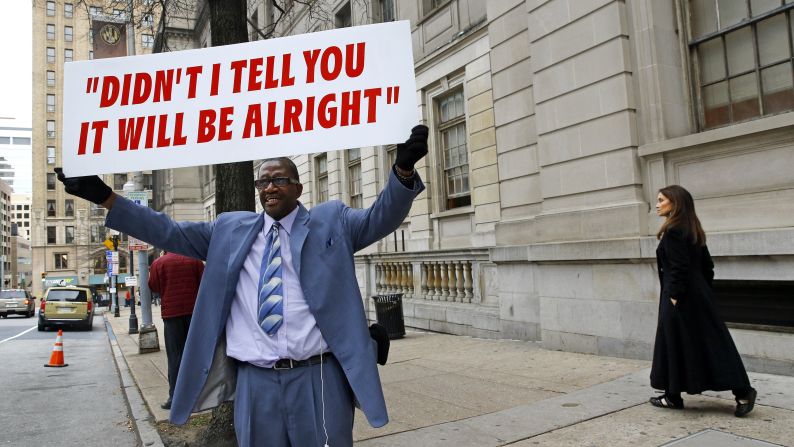

In Baltimore, a jury deliberated this week over the fate of the first of six officers charged in the Freddie Gray case. Gray died after suffering a severe spinal injury while in police custody, sparking massive protests and rioting. It’s rare that the officers were charged; it would be rarer still if any or all of them are convicted. On Wednesday, the jury was deadlocked and the judge declared a mistrial.

These cases are not isolated incidents. Media outlets from the Washington Post to The (Columbia) State newspaper in South Carolina have shown that over the past couple of decades, officers are almost never held criminally accountable for the wrong they commit in uniform, no matter the circumstances, no matter if their actions result in a broken face or a dead 12-year-old shot while playing with a toy gun in a park.

Truth be told, though, is that we don’t have to rely upon that kind of analysis. Police officers have already told us why this keeps happening: because they allow it to. It begs the question: Why are so many cops – good cops – seemingly comfortable with wrongdoing in their midst? It’s as though in their eyes, evil is only evil when it wears a bandana, not when it wears a badge.

They wouldn’t tolerate a gang member executing a man in the middle of a street or kicking a man in his face while he’s on his hands and knees. But they seem unmoved when a fellow officer does it.

Juries and prosecutors and political leaders frequently go along with that thinking, which sends a clear, chilling message to communities that already fear and distrust the police, that they have nothing to lose if an encounter with an officer goes badly because their version of events won’t be believed, and those who harm them won’t be brought to justice anyway, so why not resist?

Before McDonald and Gray and Eric Garner and #BlackLivesMatter, the Justice Department surveyed police officers from 121 departments. It released the report in May 2000. The study showed that most officers had witnessed police brutality, but that 61% of them “indicated that police officers do not always report even serious criminal violations that involve the abuse of authority by fellow officers.”

What’s more, “a substantial minority believed that officers should be permitted to use more force than the law currently permits and found it acceptable to sometimes use more force than permitted by the laws that govern them.”

From the study: “Even though most police officers disapprove of the use of excessive force, a substantial minority consider it acceptable to sometimes use more force than permitted by the laws that govern them. The code of silence also remains a troubling issue for American police, with approximately one-quarter of police officers surveyed stating that whistle blowing is not worth it, two-thirds reporting that police officers who report misconduct are likely to receive a ‘cold shoulder’ from fellow officers, and more than one-half reporting that it is not unusual for police officers to turn a ‘blind eye’ to improper conduct by other officers. These findings suggest that the culture of silence that has continually plagued the reform of American policing continues.”

The code of silence is somewhat true in most professions, but not like it is for police officers. For instance, journalists believe it is part of the job to publicly criticize bad journalism, even harshly. The reluctance by police officers to do the same damages community relations and creates distrust, making it harder to effectively fight crime. Shining light in the dark places among your own is often painful, but also disinfecting.

Seven years after the Justice Department study detailing that code of silence among police was released, a December 2007 article by USA Today reported that federal prosecutors were concerned about a rise in police brutality cases and that even large police unions were “concerned that agencies were dropping standards to fill thousands of vacancies and ‘scrimping’ on training.”

This was before anyone talked about the now-debunked “Ferguson effect,” claims by the likes of presidential candidate Gov. Chris Christie that President Obama was making things hostile for law enforcement, or that #BlackLivesMatter was the cause of distrust of police.

“In its post-September 11 reorganization, the FBI listed police misconduct as one of its highest civil rights priorities to keep pace with an anticipated increase in police hiring through 2009,” USA Today reported.

It also said that up to 96% of police brutality cases were declined by federal prosecutors “under every administration dating to President Carter,” meaning under Democrats and Republicans. (Last year, a writer for the American Conservative pointed to that fact among seven reasons why police brutality is widespread, not a result of a few bad apples. )

Why? Because the blinders cops wear when evil is perpetrated by fellow officers are often worn by jurors who refuse to believe cops can do wrong, making convictions difficult to attain.

More Justice Department investigations into police departments, like the one recently announced for Chicago, may be necessary. But as long as the public – and cops – continue accepting this level of bad behavior by police, the distrust will remain.

Many people, including President Obama, call on communities of color to help law enforcement get rid of the criminal element within their groups, whether they be black gangs or Islamic extremists. Why aren’t more of us demanding that law enforcement do the same?

Chicago Mayor Rahm Emanuel was forced to pledge to demand better accountability and transparency from the police department. He apologized for the McDonald killing.

He isn’t the only one who has some explaining to do.

Join us on Facebook.com/CNNOpinion.

Read CNNOpinion’s Flipboard magazine.