Story highlights

18,000 men a day were sidelined by sexually transmitted diseases during World War I

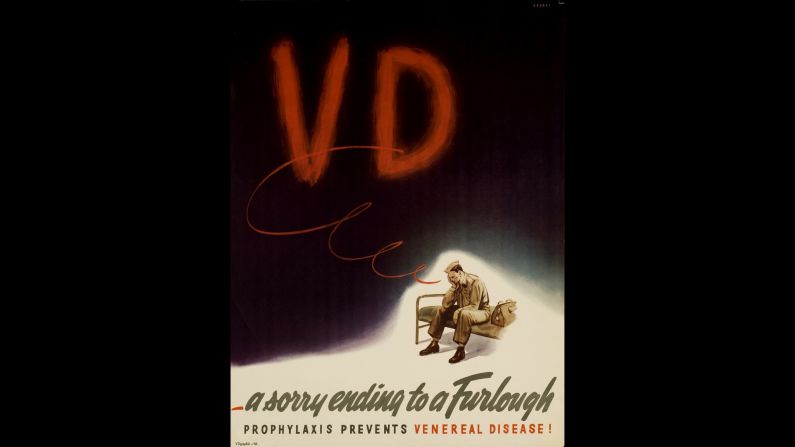

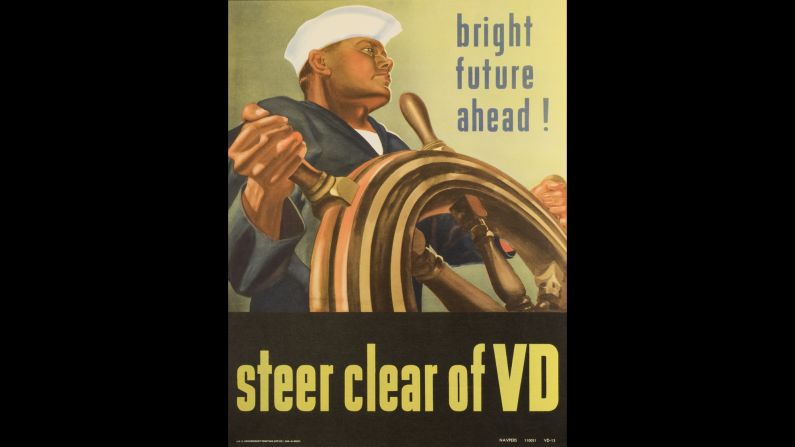

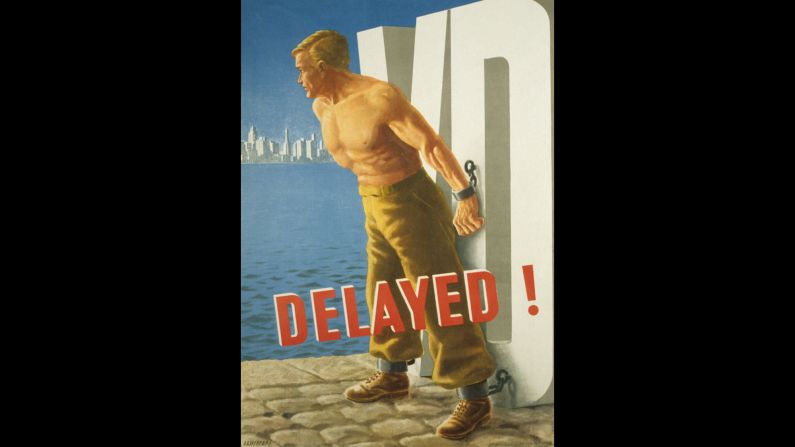

Graphic posters were commissioned to keep WWII enlisted men from the same mistake

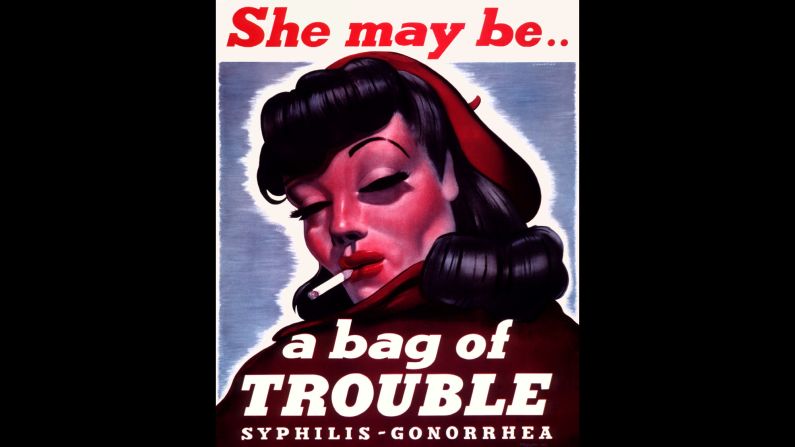

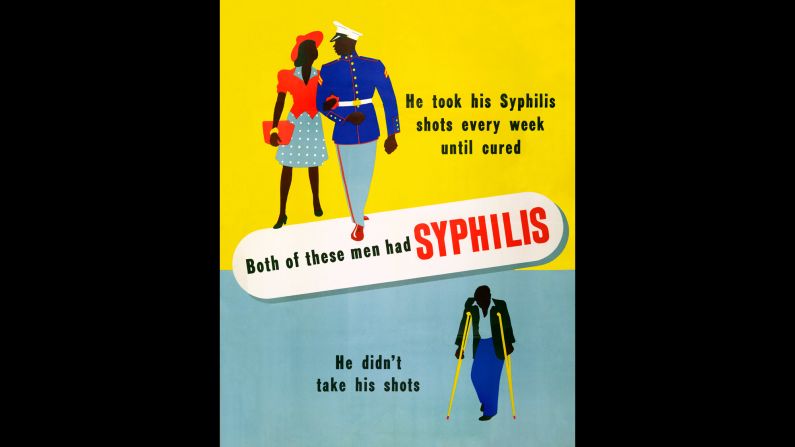

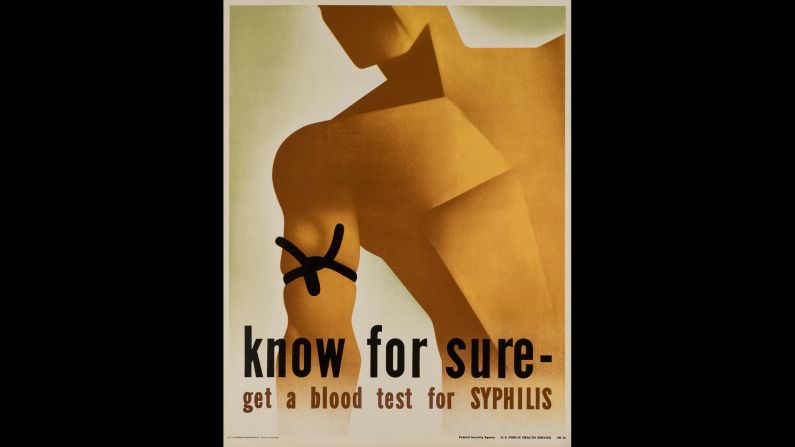

You’ve heard of Rosie the Riveter, the poster gal of World War II, right? She wasn’t the only feminine character to make a huge impression on the men in the 1940s military. Meet the shady ladies of venereal disease: the “Bag of Trouble” poster girl and her friends. They were created courtesy of the U.S. surgeon general, the U.S. Public Health Service and the Federal Security Agency in the early 1940s and given a modern audience by Ryan Mungia’s book “Protect Yourself: Venereal Disease Posters of World War II.”

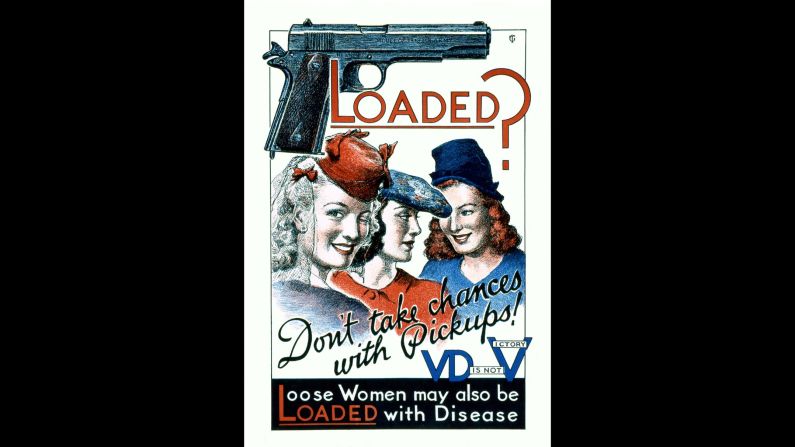

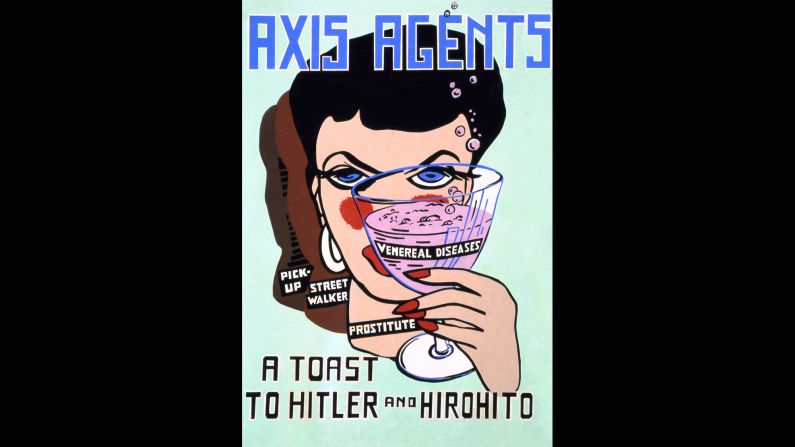

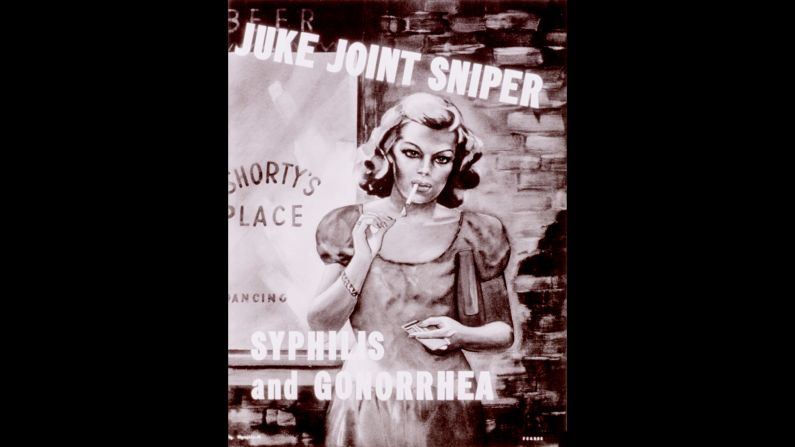

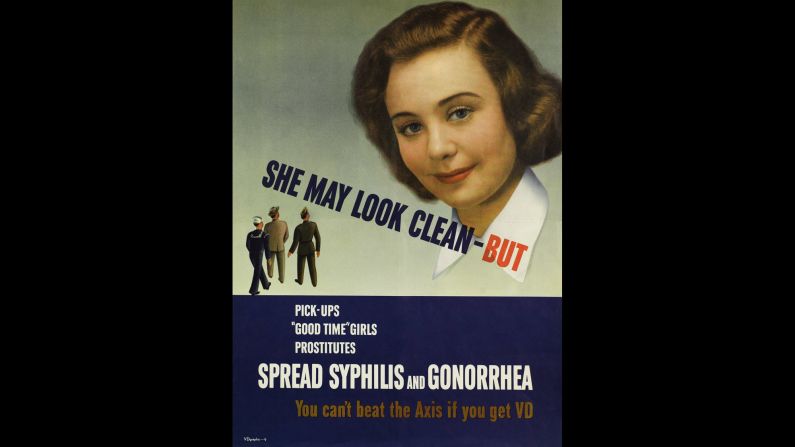

Dubbed “penis propaganda,” these attractive women were deliberately drawn with deeply etched red lips designed to entice a man into paying attention to something that wasn’t talked about openly: sexually transmitted diseases.

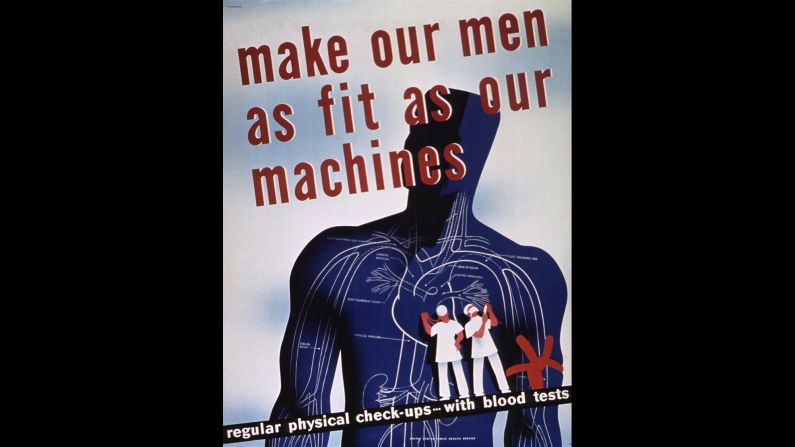

Why was the government entering such covert territory? Because it didn’t want history to repeat itself: On any given day during World War I, about 18,000 men were taken out of battle by venereal disease, and it could take a month of treatment before each man was ready to return to the front.

According to a history published in the journal Military Medicine, “In World War I, the Army lost nearly 7 million person-days and discharged more than 10,000 men because of STDs. Only the great influenza pandemic of 1918-1919 accounted for more loss of duty during that war.”

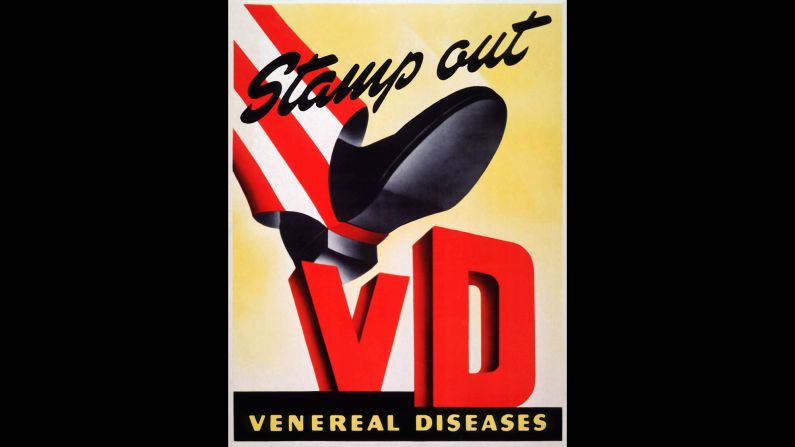

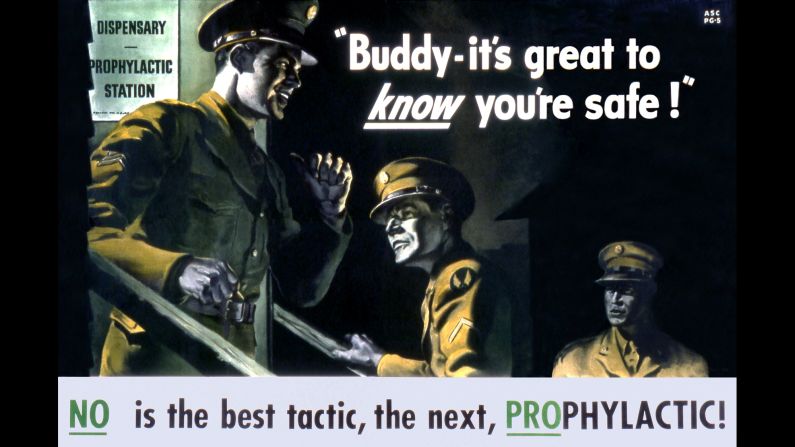

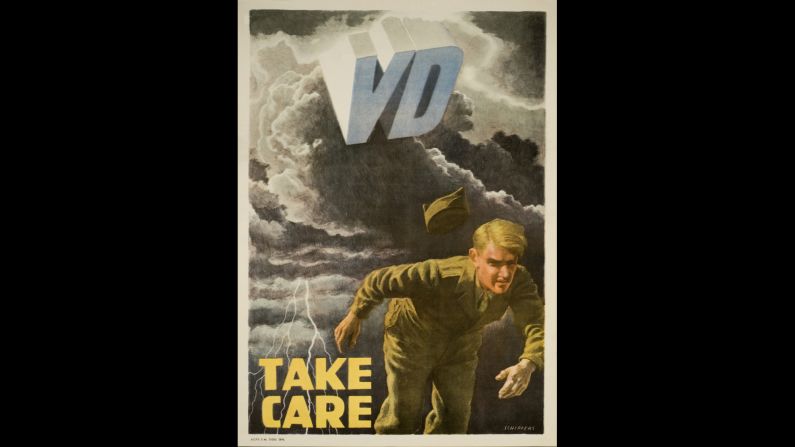

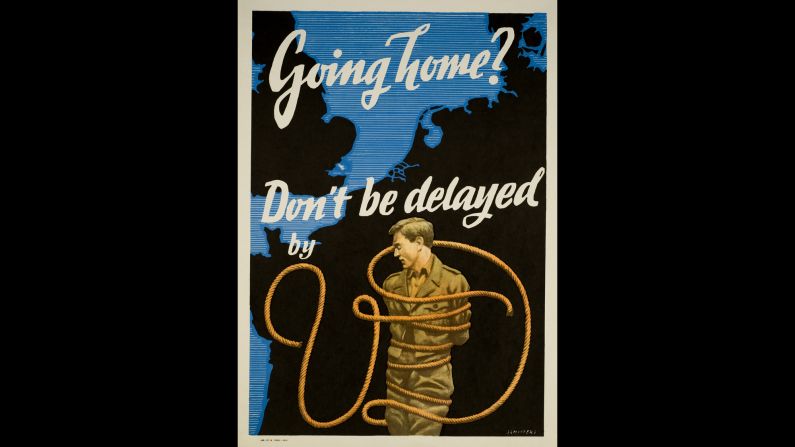

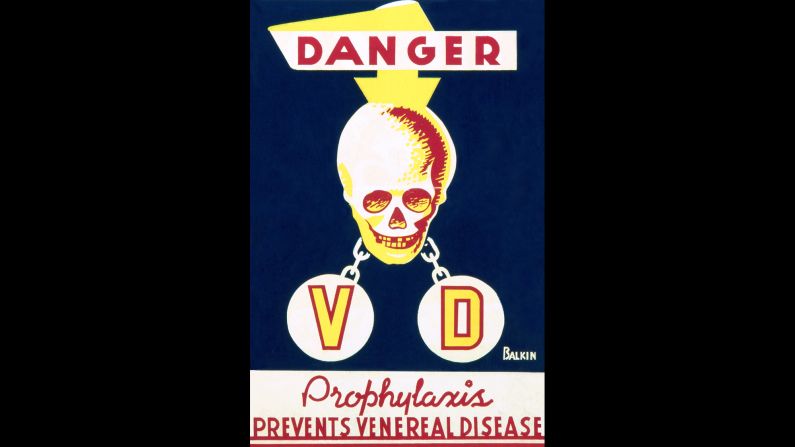

While it’s true that the introduction of penicillin and sulfa dropped those numbers dramatically by the ’40s, the threat was still real and the military didn’t want to take any chances. So it commissioned graphic artists to create eye-catching art with a serious message: “You can’t beat the Axis if you get VD.”

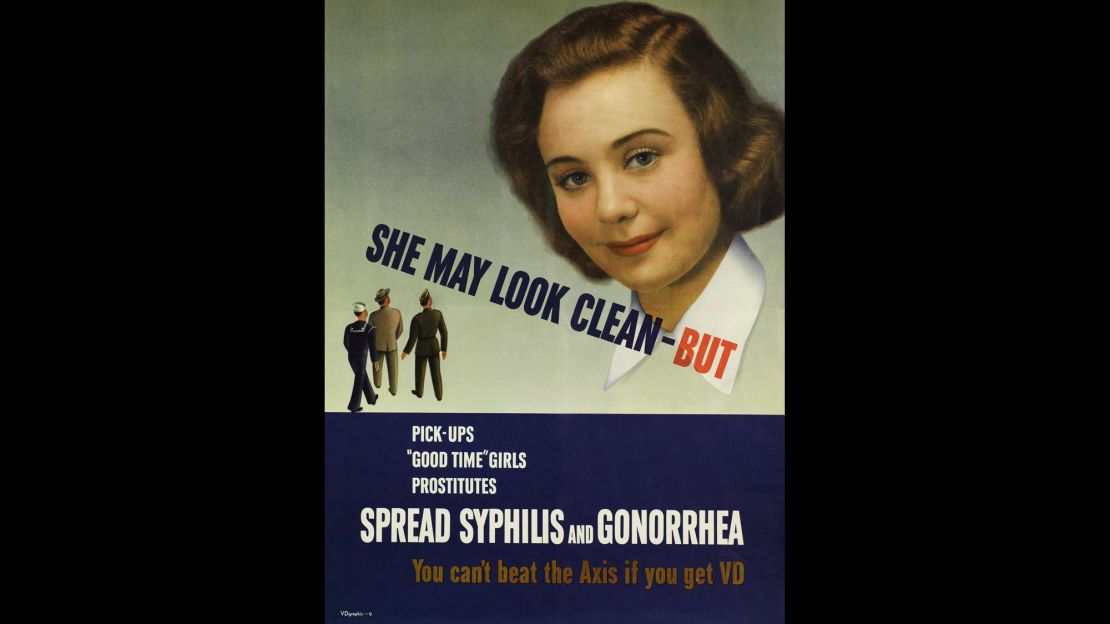

“She may look clean, BUT …” – the font is plastered over a face that could easily have won a girl-next-door movie role – “… pick-ups, ‘good time’ girls, prostitutes spread syphilis and gonorrhea.”

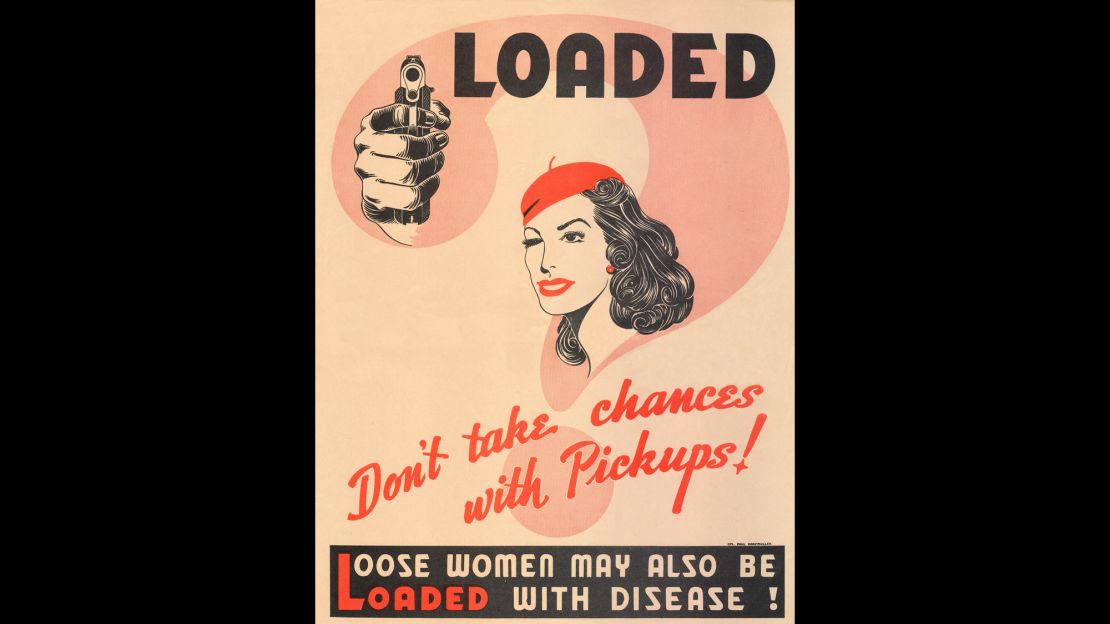

“Don’t take chances with pick-ups,” says another. Loose women could be “loaded” with disease.

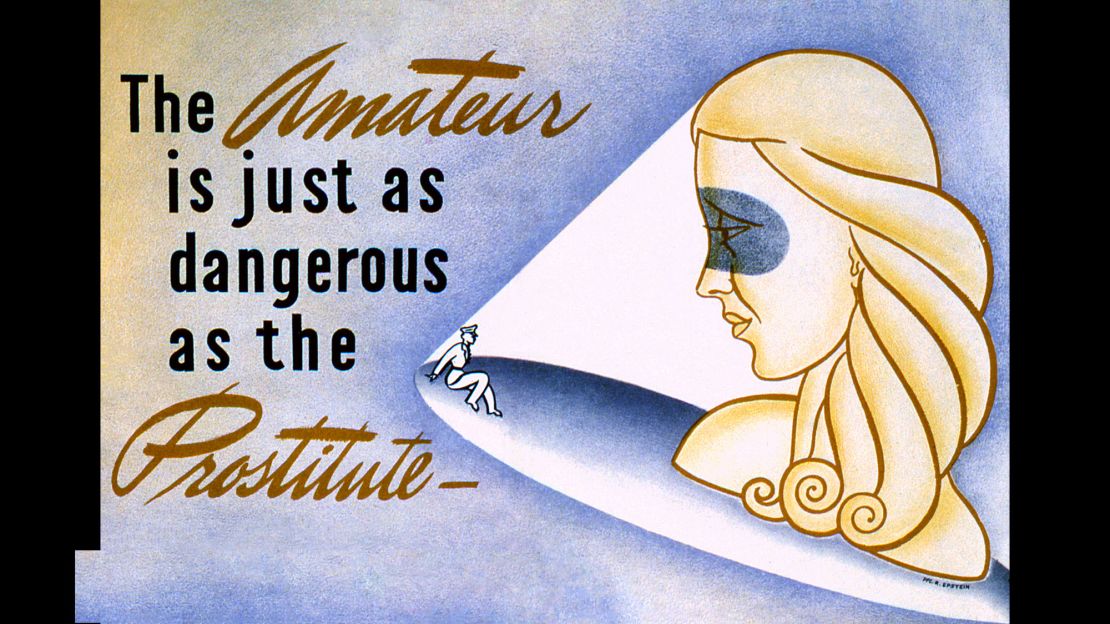

Yet another warning: “The amateur is just as dangerous as the prostitute.”

Today, the outdated images and messages make us shudder. Even back then, for those who didn’t buy the argument about “good time gals,” also known at the time as Khaki-Wackies, Good Time Charlottes and Victory Girls, the government provided a different line of propaganda. Surely Hitler and Hirohito were in cahoots to give service members VD and ensure their own “victory.”

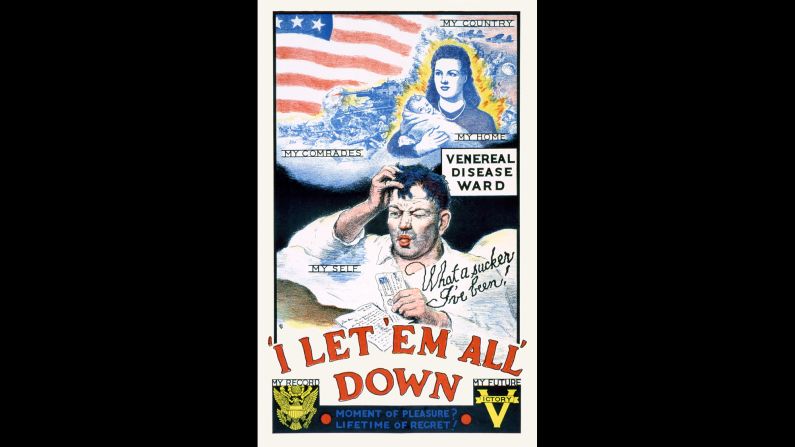

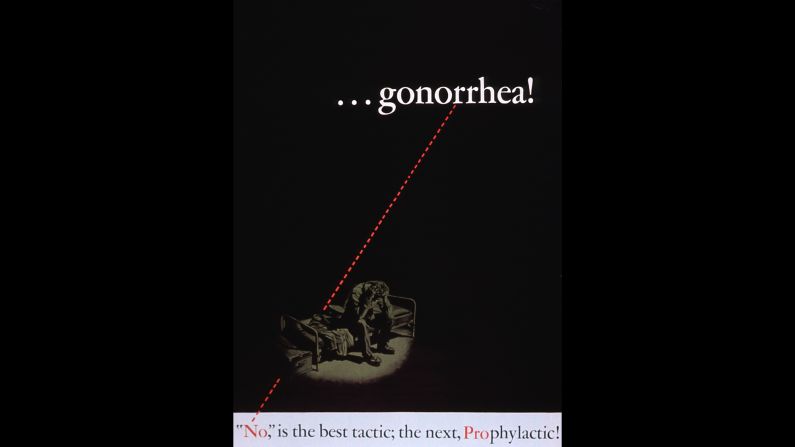

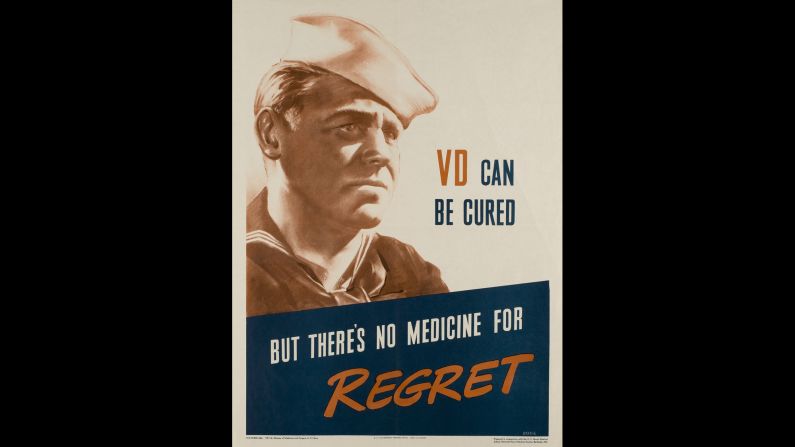

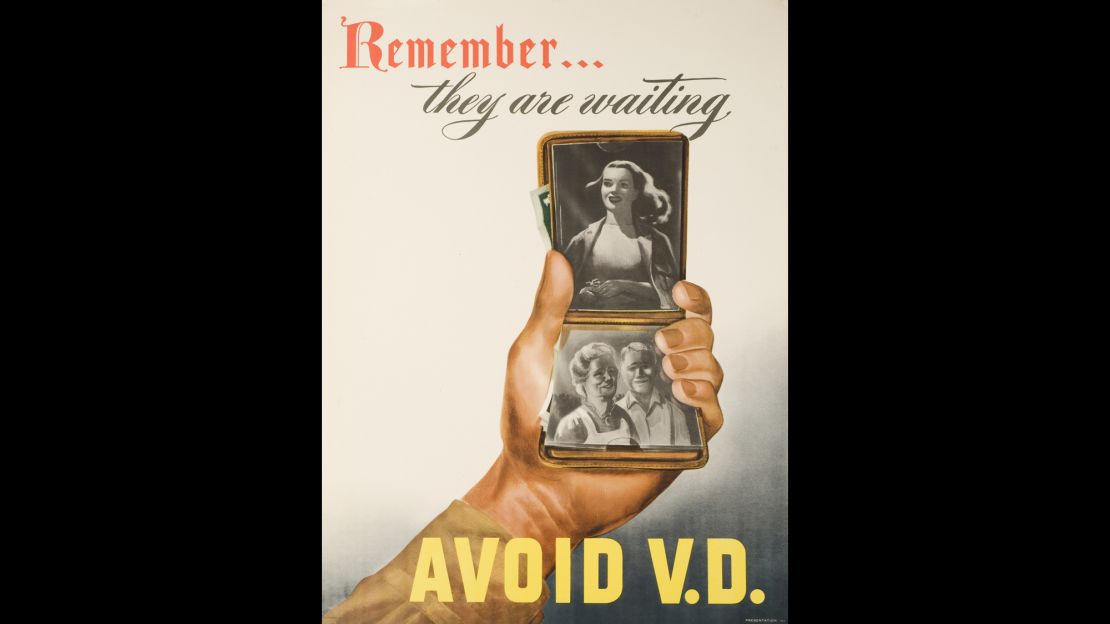

Another huge 1940s theme: guilt. “Remember, they are waiting … Avoid VD,” reads one poster that shows the wallet-sized eyes of Mom and Dad and, of course, waiting girlfriend. And another that hits all cylinders: country, represented by the American flag; home, represented by a pretty wife in pearls, holding a new baby; and self, represented by a soldier tearing his hair and saying, “What a sucker I’ve been! I’ve let ‘em all down.” Finally the punch line: “Moment of pleasure? Lifetime of regret!”

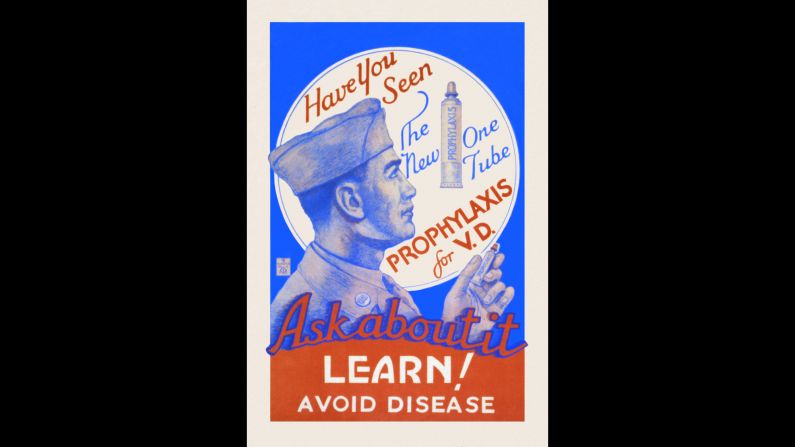

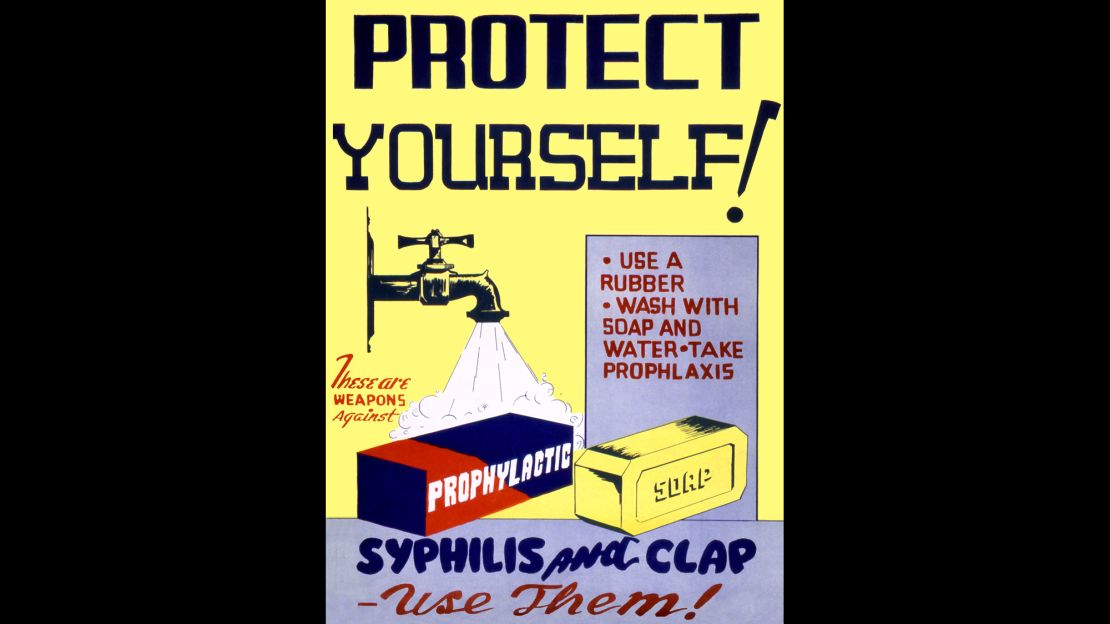

Some posters gave more specific advice. “Use a rubber, wash with soap and water, take prophylaxis” reads words next to a water faucet and soap: “These are weapons against syphilis and clap. Use them!”

Of course the big question is, did all of this “penis propaganda” keep the troops from getting STDs? Here’s the U.S. Army Medical Department’s Office of Medical History: “It can be stated very simply that the lowest venereal disease rates in the U.S. Army occurred during 1943 and that the rates began to rise in 1944, further increased in 1945, and showed marked increases after the cessation of hostilities.”