Story highlights

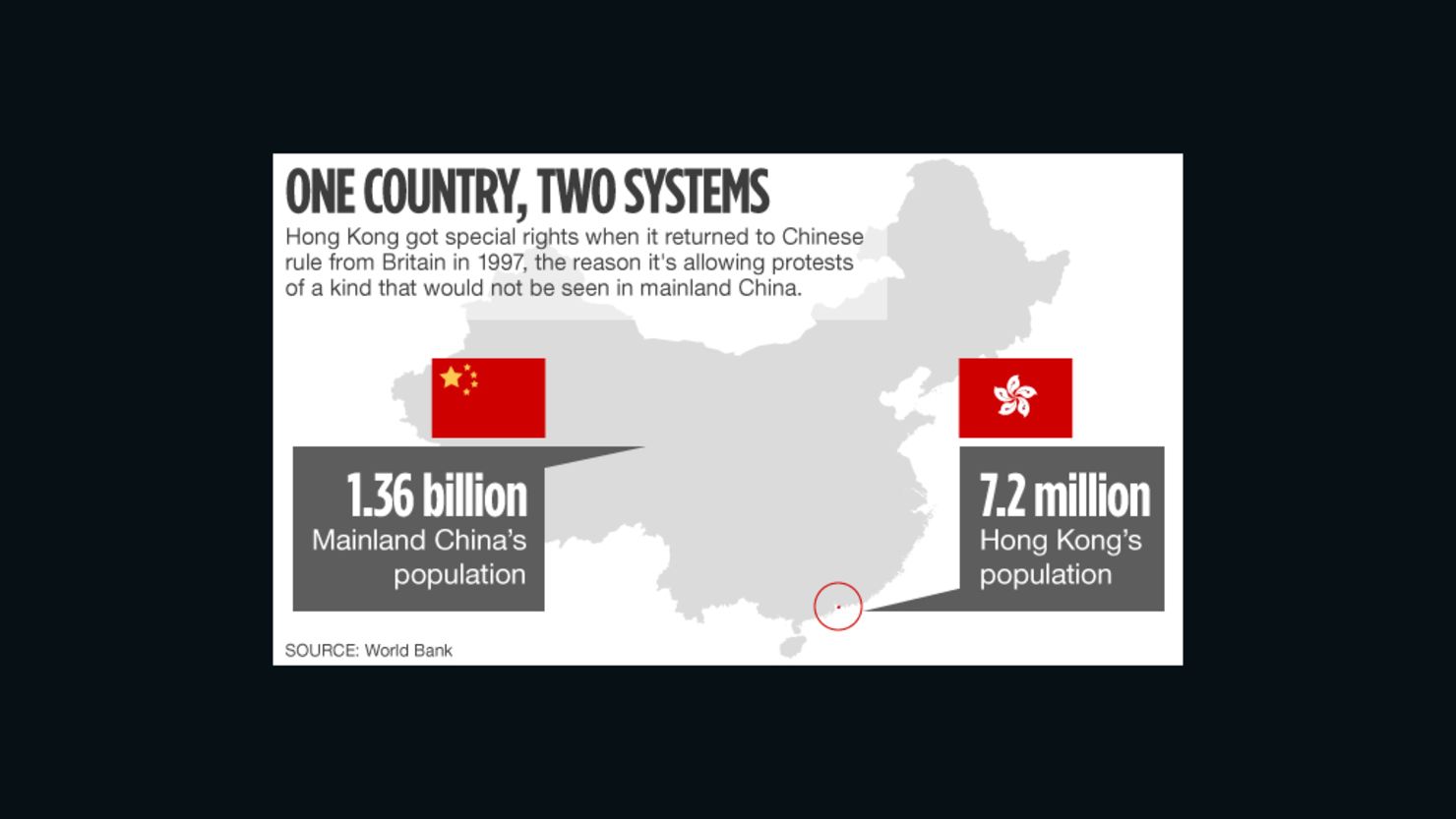

Hong Kong's "One country, two systems" governance guarantees the city a high degree of autonomy

The relationship between Hong Kong and China is often complex

British colonial legacy and institutions, as well as historical, cultural, economic, legal and lifestyle differences, remain

Hong Kong, as anyone who has lived or worked in the city knows, is simultaneously China, and not China.

The complex legal framework that was put in place when the city reverted to Chinese rule in 1997 makes it a unique case, and one which means that the delineations between the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region (SAR) and the mainland are rarely straightforward.

The differences between the two provide a wealth of reasons why they are often at loggerheads – and no more so than now, with tens of thousands of Hong Kongers taking to the streets to protest what they see as Beijing’s undue encroachment into Hong Kong’s civil affairs and political structure.

Certainly Hong Kong’s unique history has set it apart. While the former colony was returned to Chinese sovereignty, the British colonial legacy has endured, and with it a set of institutions and historical, cultural, economic, legal and lifestyle differences.

Here are just a few of them examined.

Historical

Compared with China throughout much of the city’s modern history, Hong Kong has been a bastion of peace, prosperity and, in the 1960s and 70s, a haven from the horrors of the Cultural Revolution. The city has welcomed refugees from across China, notably Shanghai, since the civil war and the rise of the Communist party in 1949.

Indeed, Chinese migrants to the port city provided the pool of skilled and unskilled labor that made Hong Kong the manufacturing hub that it once was, setting it on the path to economic success.

When a British landing party planted their flag at Possession Point on Hong Kong island over 170 years ago, they set in motion one of the most complex political relationships to endure to the present day.

While the island of Hong Kong was ceded in perpetuity following the first Opium War, the bulk of Hong Kong’s landmass, the Kowloon peninsula and the New Territories, were leased from China. When the New Territories’ lease was due to expire, in 1997, it was decided that the former colony would be returned, in its entirety, to China.

Since then the city has endured a “brain drain” in the 1980s and the early 90s, after Britain and China had agreed the handover of sovereignty, and particularly when the Tiananmen crackdowns in 1989 were fresh in the memories of those Hong Kongers who could find their way out.

There are some who fear that clampdowns on civil liberties might mean the city could soon face another exodus: “I’m worried that people might migrate again,” Michael Davis, a law professor at Hong Kong University, told CNN’s Andrew Stevens.. “That would be a disaster.”

The Basic Law: “One country, two systems”

Hong Kong’s defacto constitution, the Basic Law, states that Hong Kong will co-exist with China as “one country, two systems” for 50 years after the handover of power in 1997.

Due to expire in 2047, it states that the city “shall safeguard the rights and freedoms of the residents.”

One of the tenets contained in the Basic Law, and reaffirmed by Lu Ping, China’s then-top official on Hong Kong, was the right to develop its own democracy. “How Hong Kong develops its democracy in the future is completely within the sphere of the autonomy of Hong Kong,” Lu was quoted as saying in the state media People’s Daily in March 1993. “The central government will not interfere.”

Beijing, however, has repeatedly reinterpreted the document, and in June of this year released a White Paper reaffirming its “complete jurisdiction” over Hong Kong.

While the city enjoys many more legal freedoms than China – including, crucially, the right to assembly – this can be a brickbat for pro-Beijing voices.

“The stability of Hong Kong is crucial,” Victor Gao, director of the China National Association of International Studies told CNN from Beijing. “There are better channels for people in Hong Kong to express their positions, rather than resorting to illegal means of creating disturbances and counterproductive means of preventing other people… to go along with their lives.”

Culture and lifestyle

It is hard to foster a sense of togetherness after almost two centuries of being separate. Linguistically – Cantonese is the common tongue here – socially and culturally, Hong Kong and the mainland can seem worlds apart.

Sometimes the differences are seemingly minor; one prominent, telling example is of a video, shared on social media, of an altercation over a mainland tourist eating noodles on the MTR, Hong Kong’s pristine subway system. But even what appear to be surface differences can explode, and videos like this often go viral here, highlighting the differences between locals and their mainland cousins.

Much of the frustration is borne of the impact mainland visitors have in Hong Kong – crowding locals out of everywhere from maternity wards to high end boutiques, and pricing them out of the housing market. Around the time of the MTR incident, a crowdsourced newspaper ad warned against an “invasion” of “locusts” – mainlanders who would figuratively devour everything in their path.

For those across the border in the mainland, the perception of Hong Kongers ranges from admiration to a feeling of contempt: Following the media storm that followed the MTR noodle-eating incident, a prominent Chinese academic, Peking University professor Kong Qingdong, called Hong Kongers “bastards” and imperialist “running dogs.”

Hong Kong identity

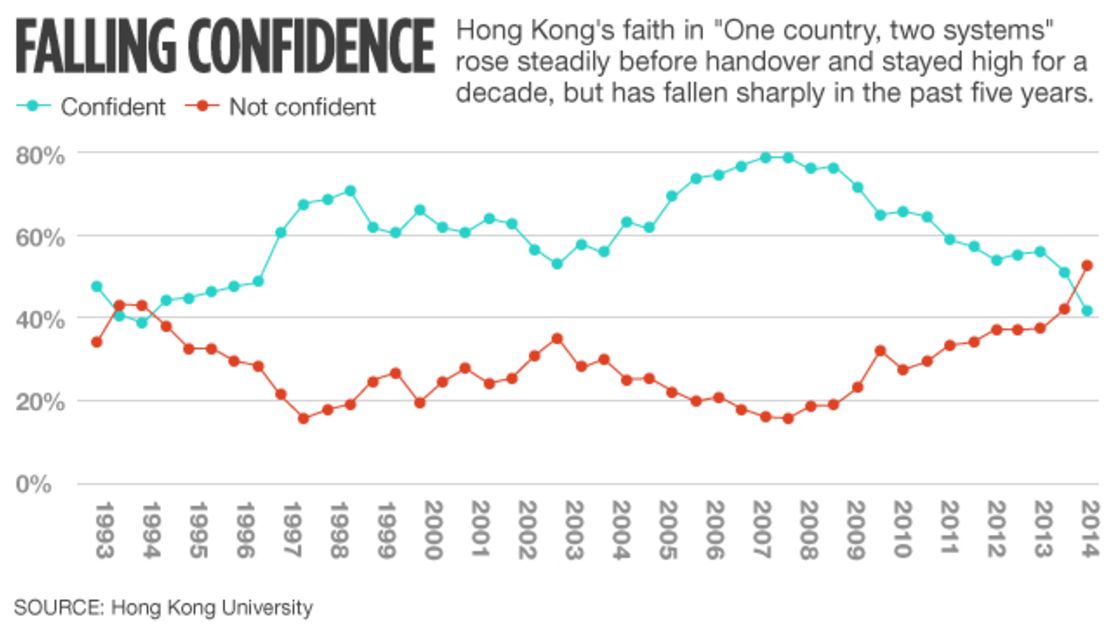

Every six months since the handover in 1997, Hong Kong University has surveyed a sample of Hong Kong residents to gauge feelings of identity in the city. The last poll was conducted in June, when over 40% of those questioned said they identified as a “Hong Konger,” rather than “Chinese” (amongst other options), a percentage that has crept up in the past 17 years.

“The protesters are unhappy because Hong Kong is becoming more and more like China,” Chinese tourist, 24-year old Liujing, from Hainan, told CNN at spillover protests in the Mong Kok region of Kowloon. “I support them because growing up, we always admired Hong Kong. If Hong Kong became like China then that would be a real shame.”

“In the mainland, first of all, we would never hear about something like this because of censorship. In the mainland, this protest would be forcibly dispersed within two hours,” she said. “Here it’s different. I don’t think police will open fire because Hong Kong is a safe place.”

“I’m not sure the protesters will get what they want, but I support them.”

Legal

Hong Kong is rightfully proud of the near-universal respect of the rule of law. For many, it is what sets Hong Kong apart from the mainland and its reputation for honesty is one of the reasons that so many multinationals have based their regional headquarters in the city.

The police generally have the trust of the population – although how this trust will be affected by the events of the past few days remains to be seen.

It wasn’t always thus; until the creation of the Independent Commission Against Corruption (ICAC), a nongovernmental watchdog in the 1960s, graft was as much of a problem here as it is in China.

Hong Kong retains a legal system which closely mirrors the British one, another holdover from the colonial era, but one which prizes transparency and due process and is largely welcomed by the populace.

The ruling Communist Party controls all aspects of China’s judicial process. However, the Basic Law, guarantees the independence of the SAR’s judiciary.

Economic

Hong Kong maintains its own currency (which is pegged to the U.S. dollar) and the city’s “capitalist” system is also enshrined in the Basic Law.

China’s oft-touted economic miracle is, at least in part, traceable to Hong Kong’s influence. Not only was the presence of the city’s free market a huge influence on the economic reforms of the late 1970s and 80s, but investment in the mainland from Hong Kong tops that from everywhere else combined.

The rest of China has benefited greatly from Hong Kong’s “investment, energy and entrepreneurship,” Hong Kong University’s Michael Davis, says.

However, as China’s economic clout grows, so does Hong Kong’s dependence on it. As a logistics center and the world’s “gateway to China” the city relies heavily on re-export of Chinese manufacturing, and inwards tourism and retail demand from the mainland is a significant earner for Hong Kong.

The mainland’s promotion of its own cities as rivals to Hong Kong – Shanghai as a free trade and financial hub, for example – could further complicate the relationship between Hong Kong and China.