Story highlights

Apartheid was more than racial segregation

It was a brutalizing regime of laws that ripped families apart and led to violence

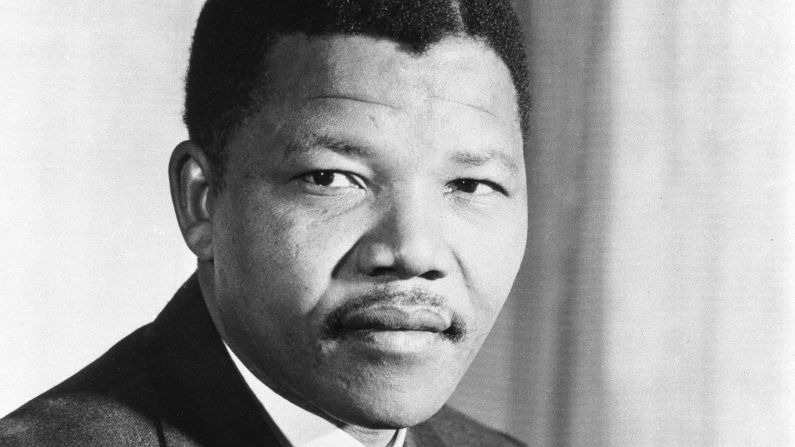

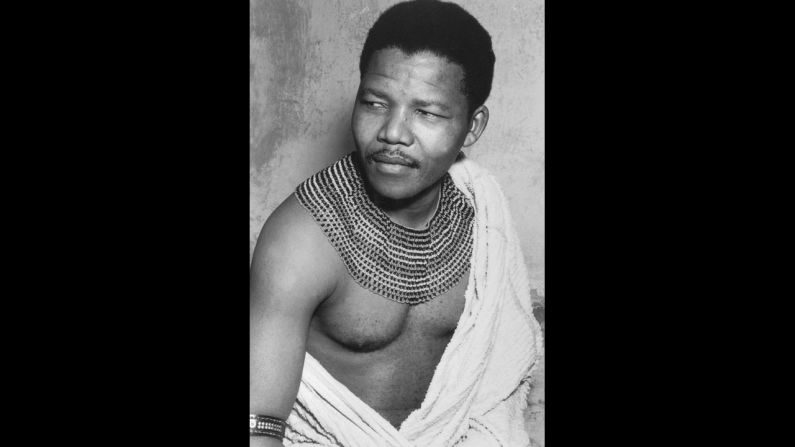

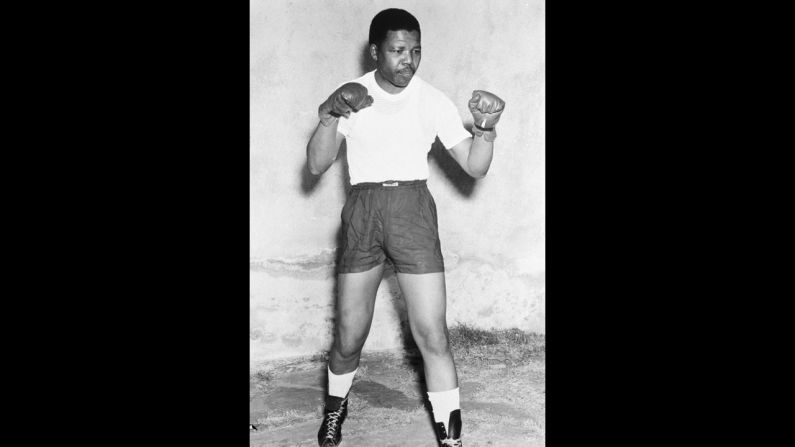

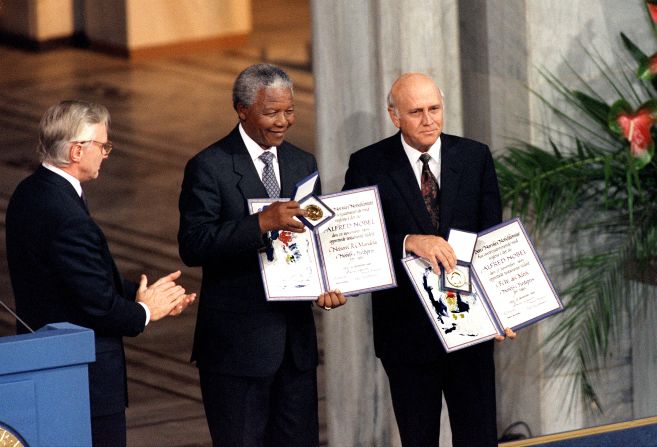

Nelson Mandela is revered for his role in helping bring down the system

Ellen Moshweu was just trying to go to church. A police officer shot her in the back on that November day in 1990.

David Mabeka was at home in 1986, sleeping through a newly declared South African government state of emergency, when police burst in to his home and took him away.

A young black man, just trying to get home, was thrown into the back of a police van and taken to jail despite the indignity of presenting a white police officer valid identity papers. The officer crumpled the pass at the man’s feet and took him to jail anyway.

Thaabo Moorsi, “severely tortured and detained.” Soyisile Douse, “shot dead by policemen.”

Families separated. Races relocated.

This was apartheid.

For many too young or too distant to remember, apartheid is little more than a distant historical fact, a system of forced segregation to learn about in history class, to condemn and to move on.

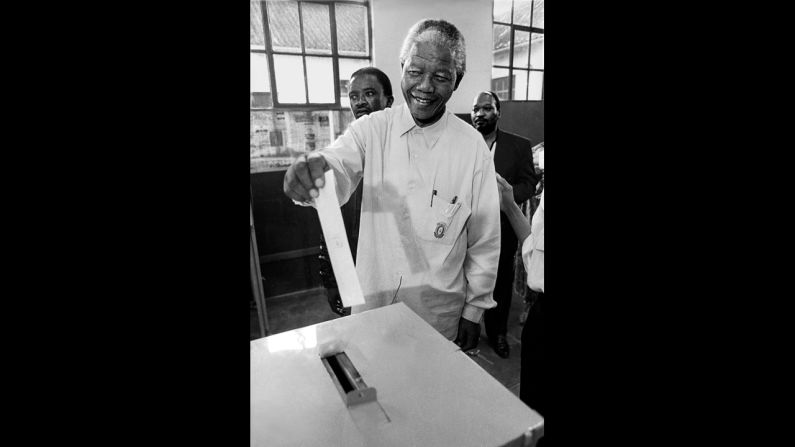

But for South Africans who survived the decades of punishing racial classification, humiliating work rules, forced relocation and arbitrary treatment by authorities, the end of apartheid was the birth of an entirely new world, midwifed in large part by Nelson Mandela.

A history of apartheid

Though white Europeans had long ruled in South Africa, the formal system of apartheid came into existence after World War II.

The country’s National Party – led by the descendants of European settlers known as Afrikaners – ushered it into existence after sweeping into power on a campaign calling for stricter racial controls amid the heavy inflow of blacks into South African cities.

Between 1949 and 1953, South African lawmakers passed a series of increasingly oppressive laws, beginning with prohibitions on blacks and whites marrying in 1949 and culminating with laws dividing the population by race, reserving the best public facilities for whites and creating a separate, and inferior, education system for blacks.

One of the laws, the Group Areas Act, forced blacks, Indians, Asians and people of mixed heritage to live in separate areas, sometimes dividing families.

Blacks had to live in often barren tribal homelands or townships near cities, often in polluted industrial areas. Whites got the best agricultural areas, the choicest city addresses.

A system of passes and identity papers controlled where blacks could travel and work.

“Ooo, don’t talk about the Group Areas Act,” the resident of one such area, Gadija Jacobs, said, according to the Apartheid Museum in Johannesburg. “I will cry all over again. There’s when the trouble started … when they chucked us out of Cape Town. My whole life came changed. What they took away they can never give back to us.”

Apartheid rules governed virtually every aspect of daily life.

Blacks had to use different beaches and public restrooms. Signs distinguished facilities reserved for whites – often referred to as Europeans.

Blacks earned meager wages compared with whites, and their children went to poorly funded schools.

In one of the telling anecdotes of the apartheid era, black nannies who dressed and fed and sang to the children of their white employers were unable to join them in the Dutch Reformed Church, the main Afrikaner congregation.

South Africa since apartheid: Boom or bust?

Growing defiance

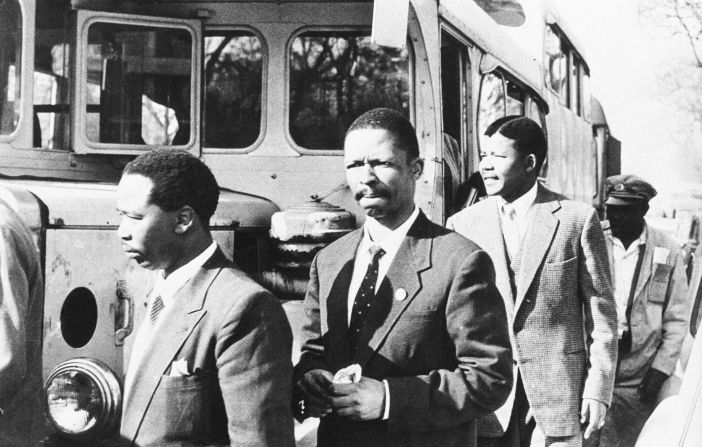

In the 1950s, growing calls for civil disobedience against the government took hold, sometimes resulting in violence as police cracked down on the protests.

The 1952 Defiance Campaign, for instance, prompted thousands of black Africans to flout the laws in hopes that their arrests would overwhelm the country’s prison system and bring attention and eventual change.

Thousands were arrested, but the African National Congress, which organized the campaign, had to call it off after scores were hurt by police.

In 1960, the tide began to turn when South African police killed 69 protesters gathered outside the Sharpeville police station for a nonviolent protest.

The killings led not only to international outcry but calls for armed struggle by the ANC and other groups.

A grim record

That struggle continued for years.

It’s laid out in gruesome detail in the records of South Africa’s Truth and Reconciliation Commission, formed after the end of apartheid to help expose and heal the country’s many wounds.

Moshweu, the woman shot in the back as she went to church, told her story to the commission in 1996.

She told an awful story, of a police officer with almost complete power in her neighborhood, a man who used to randomly fire off his gun – and who she said had also killed her son.

“He brought suffering to me by killing my son. He wanted to kill me. That is why he shot me,” she told the commission.

Mabeka, who testified at the same hearing, told the commission he spent two months in prison after being taken from his home in 1986 and beaten at a police station.

“They assaulted me with fists; they kicked me, and I fell on the ground,” he said. “They didn’t ask me anything; they didn’t tell me what do they – what did they want.”

John Biyase told his story to researchers from Michigan State University in 2006.

He recalled marching in Johannesburg in 1977 after police closed many of the high schools attended by blacks in an apparent effort to break up resistance efforts.

Police trapped the marchers and set on them as they tried to escape.

“They just hit everybody,” Biyase told his interviewers. “There was blood, cries. I remember we were shouting, ‘Peace! Peace! Peace!’ “

He spent three weeks in the city’s John Vorster Square prison in a cell with 20 other young men.

There, he remembers police threatening to take troublemakers to the 10th floor “workshop,” where police were suspected of staging fatal accidents involving inmates.

“We knew what the workshop meant,” he told his interviewers. “Death.”

Finally free

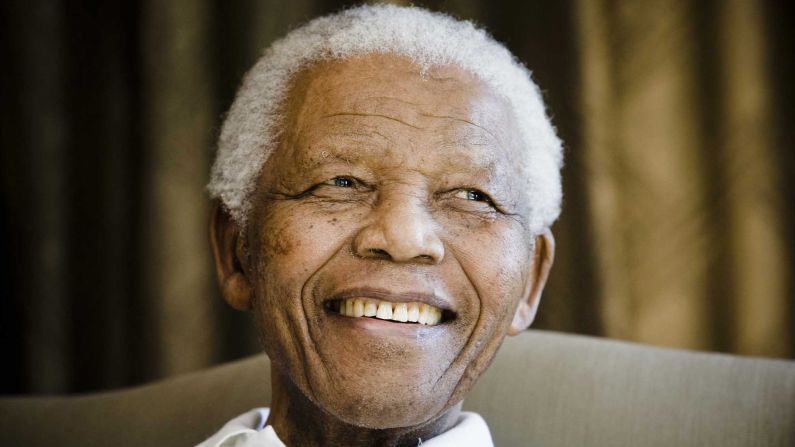

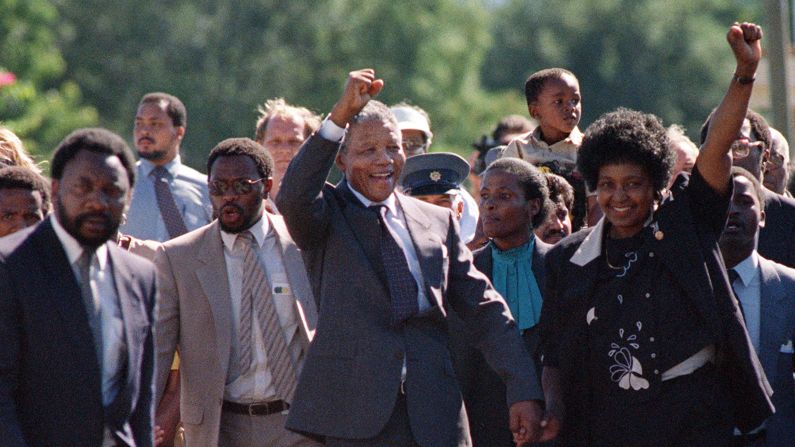

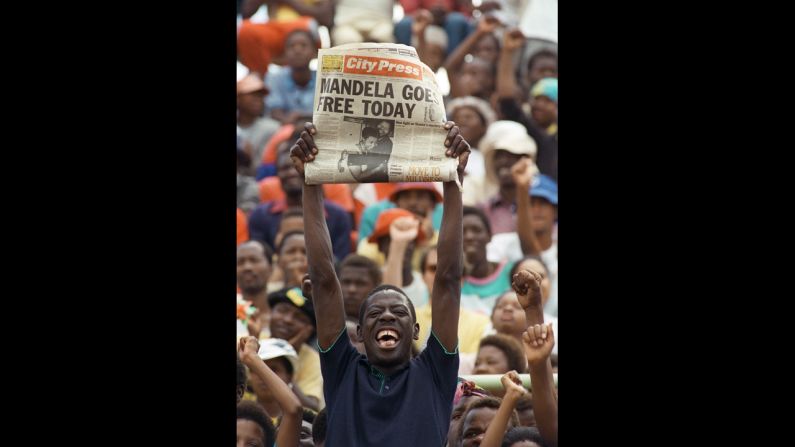

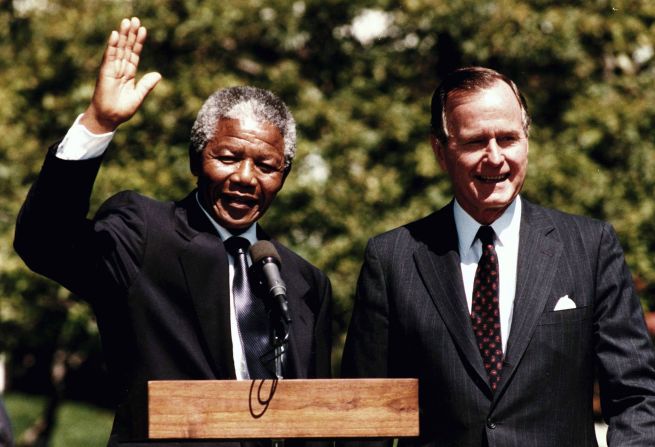

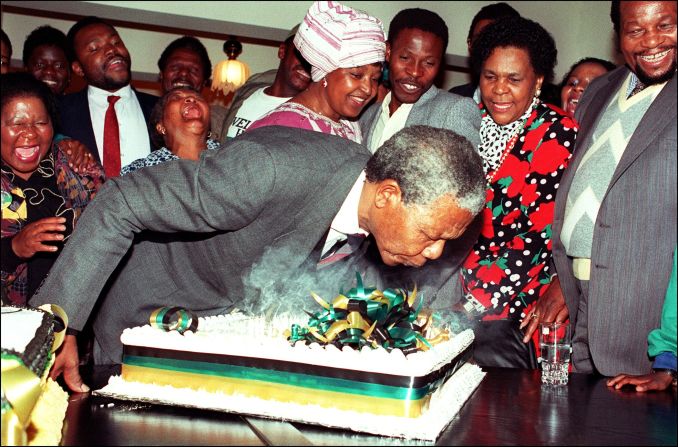

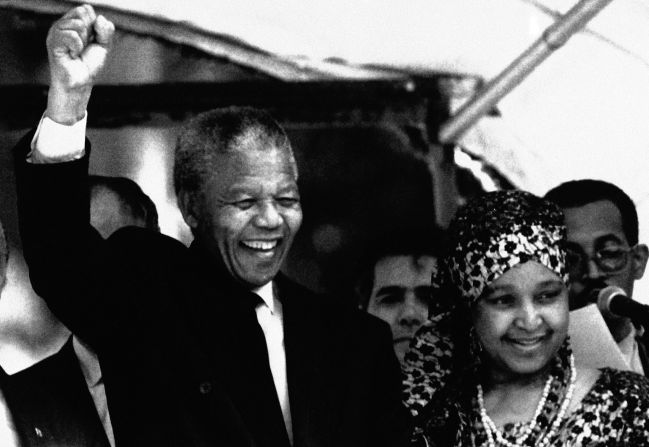

When Mandela was freed in 1990, four years before he would become president, another surprising element of apartheid reared its head.

Before his release, few had seen Mandela’s now-famous face or heard his voice.

Under apartheid, the government banned the publication of anything to do with opposition groups such as his African National Congress.

“We were fed the information we were allowed,” said Susan Campbell, a former prosecutor who now is an environmental lawyer in the coastal town of Knysna. “It was only after his release, really, that we actually saw who he was.”

Nelson Mandela: 10 surprising facts you probably didn’t know