Story highlights

A quarter of those infected with HIV are between the ages of 13 and 24

More than half of youths with HIV don't know they have it

Reasons youths don't get tested can vary widely

A message of abstinence may not work for all teens and young adults

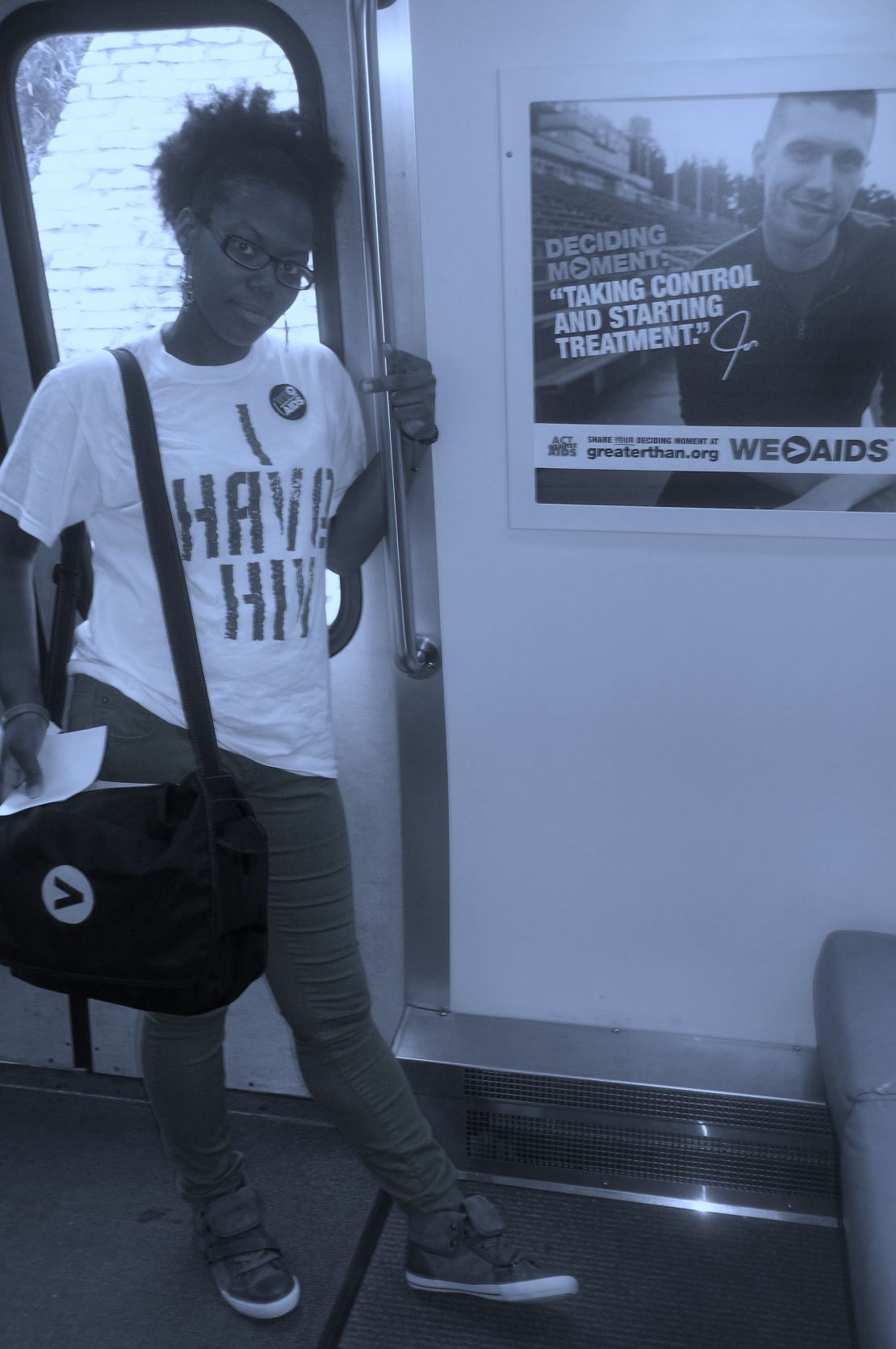

Masonia Traylor doesn’t look sick.

The 25-year-old mother of two is poised. Sitting in a boardroom at AID Atlanta, an HIV outreach facility in Atlanta where she volunteers, she exudes confidence.

But Traylor is HIV positive.

According to the CDC, 50,000 Americans are infected with HIV each year, and 25% of those are between the ages of 13 and 24.

Sixty percent of youth with HIV don’t know they have it, despite recommendations from the CDC, the American Academy of Pediatrics and the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force.

A faceless disease

Traylor got her first HIV test as a teenager when someone living with the disease gave a presentation at her high school. She was about 16 and already a teen mother at the time. She knew she had been having unprotected sex and wanted to stay healthy for her young son.

At the time, Traylor was in what she believed was a monogamous relationship. During her annual doctor’s visit, she was disturbed to realize she had to ask specifically for an HIV test on top of a standard STD panel. She insisted on taking the test even though her doctor told her – as a heterosexual woman involved in a monogamous relationship – that she was low risk.

Later Traylor broke up with her boyfriend and began a new committed relationship. That was the year her life changed. Despite vigilance in testing, Traylor wasn’t prepared for what she found out at her doctor’s visit that year: She was HIV positive. Two weeks later she learned she was pregnant with her second child.

“It was very difficult – a lot of screaming in my head, a lot of tears – as if I was going to a funeral every day,” she said.

The father of Traylor’s baby tested negative for HIV and she was able to give birth to a healthy daughter. Traylor believes she contracted the disease from an ex-boyfriend who has not been tested.

Over the past two years, Traylor has come to a place of acceptance, and she takes personal responsibility for taking a chance with her health by having unprotected sex. But in hindsight, she realizes that even though she knew about HIV, she didn’t fully understand her risk of contracting it.

“At home we didn’t talk about HIV because it just didn’t exist in my world,” she said. “I was aware it was out there, but I didn’t know what it looked like.”

HIV doesn’t have a face, and someone who is infected doesn’t necessarily exhibit any physical signs.

“You think that you would see signs that a person is sick,” she said, but since that isn’t always the case, teens and young adults can feel a false sense of security. They may think, regarding their partner, “we talk all the time, I trust them, so I don’t need to go get tested,” she said.

Traylor wasn’t always open with her status, but now she dedicates much of her time and energy to raising HIV awareness because she considers the often imperceptible nature of the disease a factor in its continued transmission.

Love, sex and stigma

Jon Diggs, a prevention specialist and counselor for The Evolution Project, an Atlanta-based center that offers HIV and STD prevention, treatment, and counseling, calls teens’ underestimation of risk part of the “invisible syndrome.”

Diggs works primarily with black gay, bisexual and transgendered men, a community that is disproportionately affected by HIV and AIDS. In 2010, the CDC estimated that 72% of new HIV infections in young people were transmitted through same-sex, male sexual activity. Fifty-seven percent of estimated new infections in this age group were in African-Americans.

Michael Kaplan, president and CEO of AIDS United, which supports more than 400 grassroots organizations annually, said that as a young gay man he found it difficult to talk to his doctor about HIV testing.

Despite seeing a doctor regularly for diabetes, Kaplan, now 44, said his doctor never offered him an HIV test and made assumptions about his sexual orientation.

“I would say, ‘I don’t date girls,’ and hoped he might simply have a clue, but (he) never seemed to allow for the fact I could be gay,” Kaplan said.

He said doctors need to create “an open and accepting environment that talks about sexuality as human nature.”

“The reality is, today, the majority of HIV infections are among men who have sex with men,” Kaplan said. “Without a doubt, we need broader screening efforts, but I think overall we need broader talk about sexuality in the United States.”

If doctors aren’t asking about sexuality and sexual activity, he said, then they miss the opportunity to recommend routine testing to young gay men.

The reasons that members of this community don’t get tested vary, but there are common threads that touch youth across all demographics, especially questions about what love and sex means after a positive HIV diagnosis.

“What is sex going to look like? … What is life going to look like? Am I going to die?” These are some of the questions Diggs hears often from those he counsels.

The fear of stigma and isolation is great enough that it “will stop people from wanting to know their status,” he said, “but it won’t stop the sexual behavior that’s happening.”

For gay, bisexual and transgendered youth, he said, the fear of isolation can be intensified for those with strong religious backgrounds. They may feel their faith or community will abandon them because of their sexual identity. Diggs said he has seen this lead to risky behavior, and he urges parents to be involved early in an open dialogue about safe sex.

This includes recognizing that a message of abstinence doesn’t always work with teens and young adults, he said, and recognizing that the conversation should be focused on sexual health, not just avoiding pregnancy. For a gay teen, he said, preventing pregnancy doesn’t translate to safer sex.

Diggs suggests moving sex and sexual health out of the shadows by making testing a regular family event and using that time as an opportunity to talk about the family’s belief system around partnering, sex and marriage.

But being open about one’s sexual health isn’t always an easy thing – a lesson Traylor has learned when she broaches the topic of dating. “When I get to the point and I ask someone, ‘Would you date someone that’s HIV positive?’ A lot of people can’t answer that question.”

Learning when to disclose her status has become part of the learning curve for Traylor. She said being upfront earlier about her status has made things better. People respect her honesty and it makes the conversation easier to have.

Other obstacles

For a teen, finding and getting to a testing facility can be a challenge all its own.

Ainka Gonzalez, prevention programs manager at AID Atlanta, said she has seen teens struggle to get tested simply because they can’t get transportation to a testing facility. For a high school student, teens must find a location that operates outside of school hours if they don’t want to involve their parents. And, if a teen tests positive for HIV, their parents may need to get involved anyway.

“Laws differ around the country, but usually if you do test positive for HIV and you’re underaged, a parent would have to consent for treatment,” Gonzalez said. “If a young person may be having other challenges at home, this of course will amplify it.”

Kaplan thinks easier access to testing is crucial. “If kids got to a place where they were routinely offered screening … they wouldn’t struggle with ‘Where can I get tested? Who do I talk to about it?’ And a lot of the stigma would be eradicated,” he said.

Learn more about HIV

Learn more about HIV

The next hurdle is paying for treatment. Teens who are too young to have their own health insurance and young adults up to age 25 who are on a parent’s health insurance plan will likely need family support to pay for medication. Without insurance, they often need to contact the department of health – an option Traylor, whose medication runs $3,000 a month, finds “terrifying.”

“At one point, I was so afraid that I wasn’t going to get health insurance anymore that I stopped taking my medicine,” she said, and hoarded medication because she expected a month-long wait for a doctor’s appointment through the department of health.

To find HIV testing facilities in your area, go to HIVtest.cdc.gov.

The next generation

Traylor feels her HIV education in high school didn’t offer crucial information about testing facilities and local rates of infection – information you can find on CDC.gov.

“In school we learn(ed) that HIV can lead to AIDS and AIDS can lead to death. … It’s a fear and that’s it.”

Today, Traylor is raising two healthy children with the help of her mother, and is educating them early about HIV.

The education starts at home, but it isn’t always easy. Traylor helped her 9-year-old son with a project on the stigma of HIV, but admitted she was nervous to talk to him about sex.

“I said, ‘If mommy had HIV, what would you do?’ He said he wouldn’t touch me, he wouldn’t kiss me, (or) hug me anymore.”

It opened the door for Traylor to talk to her son about how HIV is transmitted. Though she didn’t tell him her status, she explained to him that HIV and AIDS can’t be spread though common contact, like hugs and kisses.

“Then (he) said, “OK, Mom, I’ll hug you. And I’ll kiss you. I’ll still love you the same.”