“I only go to casinos once a year, on Chinese New Year,” says Vivian Lai, a second-generation Macao resident who is training as a nurse. The tradition of gambling is said to bring good luck for the year to come, whether you win or lose.

Macao, the Chinese special administrative region (SAR) often twinned with Hong Kong, is known as the Las Vegas of Asia. As the only place in greater China where gambling is legal, the city’s skyline is a who’s-who of the biggest names in the gaming industry.

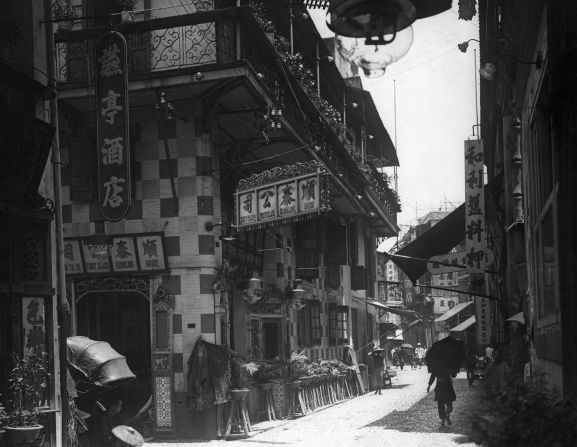

Home to just 600,000 residents – compared to seven million in Hong Kong – visitors to Macao might feel like the rest of the city lost in the shadow of the towering hotels and casinos. But travelers who are willing to dig in a little deeper can explore Macanese culture, which mixes Portuguese, Chinese and Southeast Asian heritages.

Macao is comprised of two islands – the north one, Macao itself, and its southern neighbor Taipa. For a long time, Taipa was relatively rural, and people had to travel between the two islands by boat. The first bridge connecting the two was completed in 1972. Now, there are three, with a fourth in construction.

A world in 40 square kilometers

While the rest of the world may associate Macao with gambling, its citizens don’t necessarily feel the same way.

“In Asia, [people] think that Macao is full of casinos, and I think they do not understand the other parts of Macao,” says Lai. “When I go to Europe, when I say I come from Macao, actually they don’t know where it is, so I have to say it’s a small city next to Hong Kong.”

Marina Fernandes agrees. She is an eighth generation Macanese, from one of the oldest families on the island.

Like a shrinking number of people in her community, she speaks the patua dialect, which mixes Portuguese and Chinese.

“The locals seldom go to the casinos,” she says. “It’s a very small number of people who really go to the casino to gamble. We don’t gamble. We do other things. And actually the civil servants, they are forbidden to enter [casinos]. The gambling is more for the tourists, it’s not for the locals.”

Due to rising costs of living in Macao, many employees of the casinos and luxury shops are increasingly likely to commute to work from Zhuhai, the less expensive mainland Chinese city just across the water from Macao, and to speak Mandarin Chinese instead of Cantonese.

Though Macao’s special status as an SAR means that people traveling between Zhuhai and Macao still have to go through border control, the process is speedier for permanent residents and citizens with Chinese national ID cards thanks to express lanes.

According to Macao’s 2021 census, about five-sixths of Macao’s population is ethnically Chinese. Only a few thousand are Portuguese. While Portuguese is still an official language of the city and must be used on signage and in government literature, many locals opted to learn English or Mandarin Chinese instead, especially ahead of the handover – when Macao was returned to Chinese rule – in 1999.

Getting around

Macao’s airport, located on eastern Taipa, is small but modern and easy to navigate. Home to a single terminal, most of its flights are from around the region, with regular connections to places like Singapore, Jakarta, Hanoi, Bangkok and Beijing. However, for longer-haul routes to North America and Europe, locals will have to head to nearby Hong Kong, Shenzhen or Guangzhou.

The mammoth Hong Kong-Macao-Zhuhai Bridge, the world’s longest sea-crossing bridge, was completed in 2018. It is just one of many Chinese projects intended to connect and promote the “Greater Bay Area” region.

Despite the $20 billion bridge, infrastructure within Macao is a different story. Locals who don’t have cars rely mostly on public buses. While Hong Kong has an efficient, well-organized metro system, Macao’s LRT (light rapid transit) system started in 2019 and only has one line so far. Uber suspended its services in Macao in 2017, and taxis only accept cash.

Cultural power

Fernandes spent several years living in Portugal, but says she felt alienated there and decided to return to Macao.

“We learned the Portuguese history. We know every city of Portugal. We sang proudly the Portuguese anthem,” says Fernandes. “Especially after the handover, they do not know us. They do not understand us, that we feel Portuguese.”

She says that the stereotypes she encountered about Macao involved gambling, triad gangs, and prostitution, as well as old cliches about Chinese people like that women still wore traditional qipao dresses and that men had the single braid or ponytail hairstyle.

Now retired and her children grown, Fernandes has devoted her life to preserving and highlighting native Macanese culture. She works at the Associação dos Macaense (Macanese Association) and has opened the canteen there to the public so that more people can try traditional Macanese dishes like minchi (ground meat, usually pork, stir-fried with potatoes and soy sauce). Her next goal is to open a commercial restaurant catering to tourists.

Due to its small size, Macao is strict about working policies for foreigners.

Ricardo Balocas, a Lisbon native who moved to Macao in 2013, has held a variety of jobs since relocating from Europe, including management roles at the Macao International Airport and at St. Joseph’s University, the only Catholic four-year university in Asia.

Most foreigners – like Balocas – who move to Macao are eligible for permanent residency after seven years of living, working and paying taxes. That means that they can live in Macao without a work visa and do not need a company sponsoring them.

Residents with local ID cards are also able to use the city’s socialized health care. Macao citizens and permanent residents get an annual perk in the form of 10,000 patacas ($1,240) a year from the government.

However, the rules are different for many of the workers who come from poorer parts of the world, namely the Philippines. Many Filipinos come to Macao to work as domestic helpers or as security guards in casinos and luxury shops, but they cannot qualify for permanent residency or citizenship – unless they get married to a local.

According to the annual Henley Passport Index, which ranks passports by how many destinations their holders can visit visa-free, Macao has the 33rd most powerful passport in the world, and Portugal is tied for the fifth best. Meanwhile, the Philippines’ passport is ranked 75th.

Life in ‘Little Lisbon’

Balocas estimates that about half of Macao’s expat Portuguese population left during the pandemic, as Macao had some of the strictest requirements in the world, including a 21-day quarantine.

That’s why he counts on places like Albergue 1601, a restaurant housed in a heritage building from the colonial eral, to keep the city’s Portuguese heritage alive.

“This neighborhood has the lamps in the street exactly the same as in Lisbon,” he says. “So if you walk around, you almost feel that you are in Lisbon. Sometimes I even joke that you can come here and take some pictures and say that you are in Lisbon without being in Lisbon.”

However, Balocas says that whether you love or hate casinos, it is impossible to ignore them. He sometimes joins a poker game on his day off: “I like to play against people, not machines.”

He cites a recent government program that “pairs” casinos with specific local streets and shops and encourages their guests to go there and spend money, as a positive move forward. In his opinion, getting hotel guests to venture outside into Macao – which is densely packed and easy to navigate on foot – helps the whole community.

“What I want people to explore when they come to Macao, it’s to get out from the casinos, honestly,” says Balocas. “There is a lot to explore. We have beautiful museums, beautiful neighborhoods.”

These days, Balocas is working at a hospitality group, managing Albergue 1601.

When he has friends or family in town, he says, the first stop is the Macao Tower observation deck, so they can see just how small and compact the city is.

“Even nowadays that I’m 11 years here, sometimes I like to get lost. Don’t just explore the center, explore the alleys.”