Think of Rio de Janeiro and the first image that comes to mind – no matter your own belief system – is probably a religious one.

Perched on the Corcovado – a 2,300-foot-high granite outcrop looming above the city – the Cristo Redentor (Christ the Redeemer) statue sweeps its arms out in a warm embrace, welcoming visitors to the city of samba.

“The first thing we see when we arrive at the city’s two airports is this brother of ours welcoming us with open arms,” says Rio designer Gilson Martins, whose handbags have been seen on the arms of everyone from Madonna to Michelle Obama. Does he look for the statue when he arrives home after a trip abroad? No, he says – because there’s no need. “It is he who finds me when I arrive in Rio.”

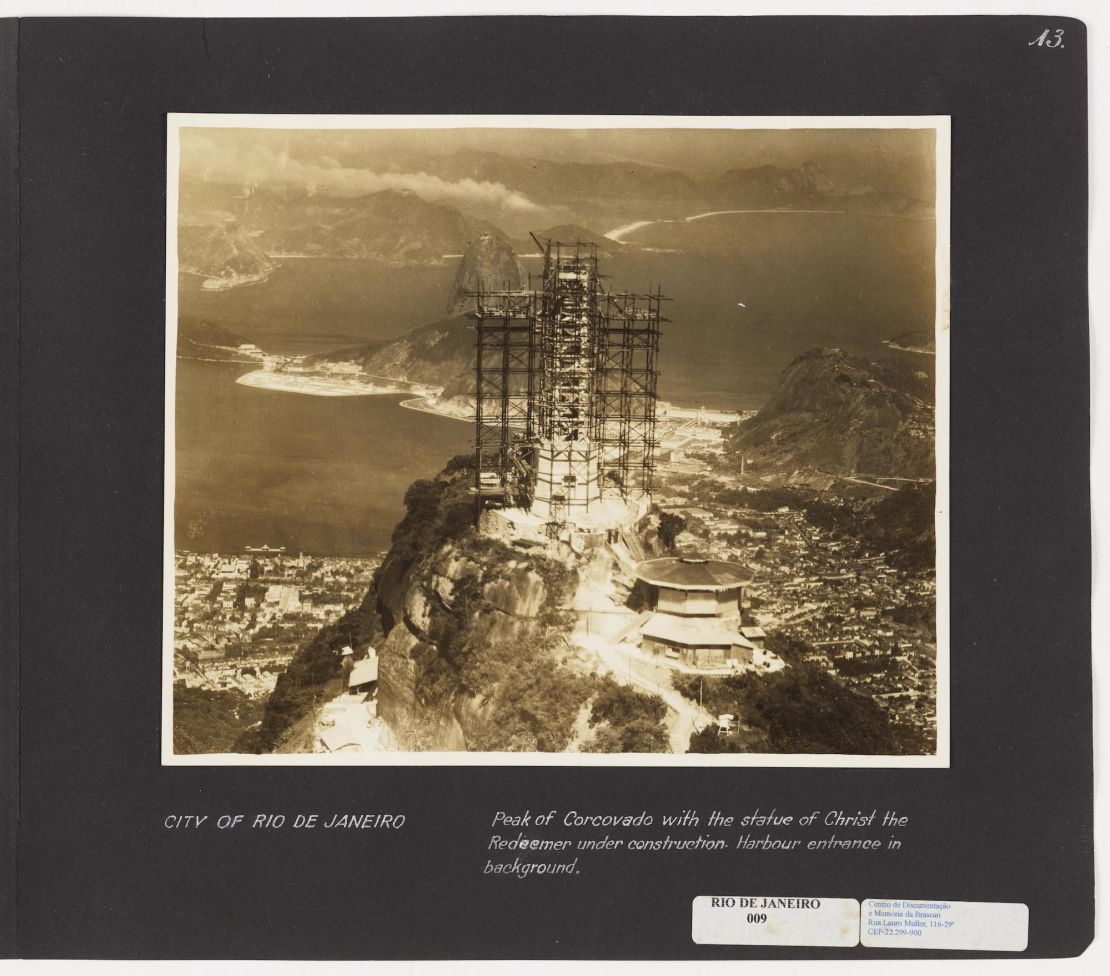

For over a century, the statue has been a symbol of Rio de Janeiro. In February 1922, architect Heitor da Silva Costa won the competition to design what sounded like a foolhardy project: an enormous statue of Jesus teetering on a high mountain peak as slim as a toothpick. It was inaugurated nine years later.

Yet nearly 100 years on, the statue – 98 feet high with an arm span of 92 feet – is still standing, and is today a symbol of the city, known all over the world. Is it a miracle from on high? Or a testament to the engineering prowess of the Brazilians who built it?

For Paulo Vidal, architect and Rio superintendent of the Instituto do Patrimônio Histórico e Artístico Nacional (Institute of Historical and Artistic Heritage, or IPHAN), which approves any restoration projects, it’s the latter. “Civil engineering in Brazil has always been at the forefront of the world, especially in reinforced concrete construction,” he says.

And therein lies its secret. Although the Christ the Redeemer looks like a stone sculpture, it’s actually what Vidal calls a “concrete building covered in soapstone tablets.”

That doesn’t mean the construction of it wasn’t heroic, however.

Turning back a ‘sea of godlessness’

The statue’s genesis came from what was essentially an act of religious propaganda: a bid to turn back a post-World War I “sea of godlessness” by installing a figure of Jesus Christ to watch over Rio, visible from anywhere in the city – an omnipresent god made stony flesh. A competition to design the statue was held and Da Silva Costa – who imagined it almost as a sun salutation, having Jesus illuminated by the dawn and ringed by a rosy “halo” at sunset – won the commission.

It wasn’t always going to be the simple figure that we see today. Initially he designed the sculpture as Christ on the road to Calvary, carrying his cross and a globe in his other hand. Luckily, with the help of artist Carlos Oswald, he switched to the more streamlined, modernist design, in which Christ’s outstretched arms not only form the shape of the cross themselves, but seem to embrace the city below it. French-Polish sculptor Paul Landowski collaborated on the final design, streamlining the shape even further, bringing it in line with Art Deco style that was all the rage at the time.

Building such a colossal structure was always going to be difficult; building it on top of a high, perilous peak even more so. Not just because of the difficulty of construction; but also of maintenance. “The big challenge was to design a project that would withstand the weather,” says Vidal, who says that the peak of Corcovado is “exposed to very aggressive atmospheric conditions.”

What’s more, this was to be a sculpture for the ages, “carefully designed to withstand the elements and to stand the test of time as a symbol of human ingenuity and devotion,” says Vidal.

Rio architects were already adept in concrete – the A Noite building, a city newspaper headquarters, was the highest building in Latin America when it was inaugurated in 1929. Da Silva Costa and his team used that experience, cladding the Christ’s concrete core in steatite, or soapstone, which is known as an insulator, and was traditionally used as cooking pots in the state of Minas Gerais, Vidal explains. It’s tough, too – a century on, the cladding is still “well preserved,” he says.

The team decided on a mosaic effect – invisible from far away, but adding detail for those who made the pilgrimage to see it up close. Soapstone was sourced from a quarry in Minas Gerais, chosen for its calm, gray-green hue. It was carved into small pieces – just over 1.5 inches in length and 0.2 inches thick, according to Márcia Braga, the architect and restoration expert who led a major conservation project of the monument in 2010 – and attached to the cement “body.” There are around 6 million tiles on the Christ Redeemer in total.

Work began in 1926, funded mainly by the church in Rio, and on October 12, 1931, the statue was inaugurated. Today, it’s part of the “Carioca Landscapes between the Mountain and the Sea” UNESCO World Heritage site, established in 2012. Four years earlier, the statue had been listed by IPHAN for its historical importance. It had been declared a municipal heritage site in 1990. It’s also the largest Art Deco statue in the world.

Constant conservation

Of course, the same ingenuity that Vidal refers to regarding its engineering has also been on full display during the past century as extreme weather batters Corcovado. The fact that a visit to the Christ the Redeemer – either taking a tiny train to the peak, or hiking up – is a must-do activity in Rio, with around 2 million visitors per year, means it’s even more important to keep the statue safe.

It’s no easy task. “Conservation is a major challenge because it’s exposed to very aggressive atmospheric conditions – whether that’s the sun’s rays, which cause the mantle and structure to expand and shrink every day, or the southwest winds that hit the statue laden with salt and sand, causing constant abrasion to the coating,” explains Vidal.

Then there’s lightning. Rio de Janeiro is a city of storms, and this high peak attracts strikes like bees to a honeypot. Lightning rods were originally built into the statue’s head to help with strikes. Vidal says that these have been expanded over the years, as storms increase in intensity. In 2021, the ‘crown’ of rods was quadrupled in size, and the earthing system was expanded.

The statue has undergone a major conservation effort every decade since 1980, but Vidal says the site is “constantly” monitored for any emergency maintenance that might be needed. “We know the materials, the degradation processes, the aggressive agents and the behavior of the structure,” he says.

The Christ has five large, covered holes for conservators to enter inside – one on top of its head, and four more on the shoulders and elbows. There are 14 smaller holes which, when open, help with air circulation, says Braga.

“Inside the statue, you feel as if you were totally protected from the weather and environment,” she says. “There is silence – it is a very strong structure, and as you are climbing to the head, the spaces to cross through get very narrow. When you finally get out on the top of the head, it is a wonderful sensation of freedom.”

Replacing 300,000 tiles

Braga – who calls the restoration project an “enormous responsibility” – was 50 when she worked on the statue. “I felt as if it was a great event in my professional career,” she says.

In a 2011 paper about the project, shared with CNN, she wrote that her team found spores from the Atlantic rainforest on the statue – making the monument even more redolent of Rio and Brazil as a whole. The bacteria were cleaned off with steam and water jets at 158 degrees Fahrenheit. The statue was also regrouted.

No detail is ignored during the conservation projects, the most recent of which took place from 2020-2022. The soapstone from the original quarry has run out over the past century – “this color is increasingly difficult to find in the natural world,” wrote Braga of her conservation project – so when pieces of mosaic need replacing, conservators carefully look at stone from other quarries in Minas Gerais, to try and match the original color as best as possible.

During her renovation, Braga rejected 80% of the replacement tesserae, picking only those that best matched the original color. She also replaced stones that had been added in previous restorations but weren’t a good color match, replacing 5% of those 6 million tesserae in total.

Such herculanean efforts are worth it, says Vidal. “Christ the Redeemer is an iconic image that publicizes the city and the country to the world,” he says. “It attracts tourism and consequently foreign currency to the city.”

Gilson Martins agrees. Christ Redeemer bags are his top sellers, tied with those sporting the Sugarloaf Mountain.

‘Like a childhood friend’

For cariocas – the inhabitants of Rio de Janeiro – the Christ has become like a family member. Tom Jobin, the bossa nova grandee who composed The Girl from Ipanema, wrote of its “open arms over Guanabara” in his song, Samba do Avião. Another song was called, simply, Corcovado. “Da janela, ve-se o Corcovado, O Redentor, que lindo,” he wrote – “From the window you can see Corcovado, the Redeemer, how beautiful.”

Martins himself has produced two art exhibitions centered around the sculpture, and has recently made an EP, singing about the statue in three of the five songs. In fact, he says, it was his childhood memories of observing the statue that inspired his songwriting.

“To me, he is my brother, my friend of many years, always present in my life,” he says of the Christ. “The feeling is like having a childhood friend with whom I have a lot of intimacy, and he is always there for us to talk to.”

Martin’s deep devotion to the concrete statue is a sentiment shared by cariocas across the city. “For me, as a carioca, architect and urban planner, Christ the Redeemer is a landmark of territorial identification. If I see Christ the Redeemer I know where I am, and that I am at ‘home,’” says Vidal. “In order to be sung about in music, the statue needs to be loved by the population – and it is. It welcomes and embraces residents and visitors.”

For Francesco Perrotta-Bosch, architecture critic and the biographer of modernist architect Lina Bo Bardi, Corcovado is “the most democratic landmark in the city.” Rio de Janeiro is famously a place where great wealth and poverty live side by side, but in a sense, the sculpture unites them.

“You can see it from rich neighborhoods and poor neighborhoods,” he says. “Cariocas can observe it from the south or north zone and will have a reference to find themselves in the city. Largely due to Corcovado, Rio becomes a city with many visual elements that help a visitor not to get lost in it.”

‘Some people cry’

Tourists seem as fond of the statue as locals. Deemed one of the seven modern wonders of the world, the Christ the Redeemer is Rio’s most visited attraction, says tour guide Cristina Arroio.

Her guests “think it’s amazing. Some people are very sensitive and they cry. Some say it’s a dream come true to go all the way up and be close to the statue,” she says.

Gilson Martins, who can see the statue from his home, calls it “the carioca host that welcomes Rio, Brazil and the world with open arms.”

“The atmosphere of Rio is formed by an intense energy of human warmth, relaxation, joy, lightness, sensuality, and receptivity,” he says. “Christ on top of Corcovado is the accomplice to all this carioca spirit. It complements all the beauty of the beaches, the Sugarloaf Mountain, the carnival, the samba dancers, and the entire carioca way of being.”

How fitting for laid-back, multicultural Brazil, that a sculpture built as a symbol of one religion has ended up representing the welcoming atmosphere of the entire country.

Maybe that’s the ultimate miracle of Christ the Redeemer.