On a Sunday evening in Hanoi’s Old Quarter, you’ll likely hear the purr of motorbikes, calls of street vendors and clicks of camera shutters as wide-eyed tourists capture the city’s manic atmosphere. But if you find yourself wandering along Hang Bac – also known as “Silver Street” – another sound might catch your ear.

After all, the otherworldly tones of ca trù – one of the most revered musical genres in Vietnam – are hard to ignore. An ancient Vietnamese tradition of sung poetry, the art is more than 1,000 years old.

In 2009, UNESCO inscribed ca trù singing as an “Intangible Cultural Heritage in Need of Urgent Safeguarding.”

After you travel to Vietnam and hear ca trù for the first time, you’ll understand why. But as practitioners age and the younger generation loses interest, there’s a fear that ca trù may be on the verge of extinction. Fortunately, there are those working to keep this unique piece of Vietnamese culture alive.

High-class beginnings

Barley Norton, a senior lecturer in ethnomusicology at Goldsmiths, University of London, first encountered ca trù in 1994.

“I think [ca trù] is an acquired taste, it sounds very alien to people who haven’t heard it before,” Norton tells CNN. “But once you become acclimatized to the subtleties of the music and the unusual vocal style, it becomes more interesting.”

The Vietnamese answer to opera, ca trù is sung in a dramatic, full-throated manner – always by a woman. Song themes range from love and attraction to the beauty of Hanoi’s West Lake.

Traditionally, ca trù was exclusively the domain of Vietnam’s literati and moneyed elites, but eventually found its way into “singing bars” around Hanoi. The musical form has drawn comparisons, perhaps tenuously, to the history of geisha performances in Japan.

Both genres have origins as high-class entertainment. And both, over time, suffered from besmirched reputations as guises for vice.

After the communist takeover of northern Vietnam in 1945, the genre was branded as being tainted by prostitution and French colonial influence. Ongoing wars also contributed to ca trù’s decline. But a lot of pre-revolutionary culture that was previously frowned upon after 1954 is now seen as an important part of Vietnam’s cultural identity, says Norton.

A ca tru renaissance

In the past three decades, ca trù has enjoyed a modest revival thanks to renewed support from the government and efforts of a few passionate musicians, such as Bach Van.

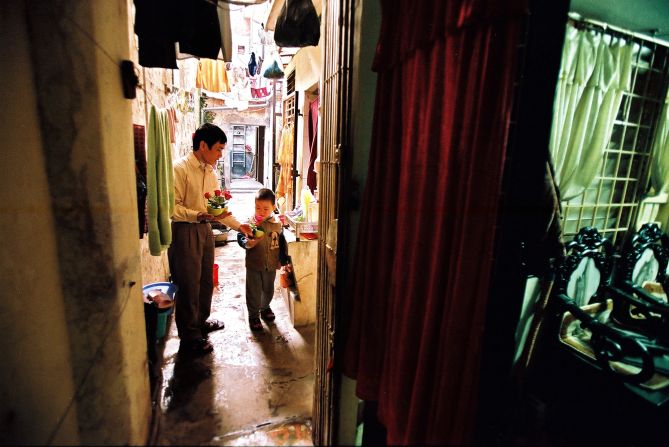

Decked out in a fuchsia ao dai – a national dress that resembles a tunic – the 60-year-old performer is one of Vietnam’s most prominent ca trù singers. She’s been singing for more than 30 years and started the Hanoi Ca Trù Club in 1991 to expose the public to the music. Van performs every Sunday evening in Dinh Kim Ngan house – a centuries-old communal property.

Meet the master

When Van opens her mouth, an otherworldly sound fills the room. She employs a mix of breathing and vibrato – a rapid variation in pitch – to create distinctive, ornamented sounds. At times, her singing sounds like braying, at others like humming. By turns lilting, by others plaintive, yearning.

Her voice crescendos, breaking at the top into tonal decorations, like ripples from ocean waves. There are 56 different melodies found in ca trù, with no fixed beat.

“It doesn’t follow a pulse, so it’s unusual in that aspect,” says Norton. “It’s improvised to some extent.”

While the ca trù singer performs, she taps out a rhythm on a small bar made of bamboo. Van says that she can hit this instrument before, during or after her singing, but the rules by which she does this are very strict.

Two other instruments accompany the singer – a three-stringed, backless lute (at 5.5 feet tall one of the longest stringed instruments in the world) and a “praise” drum.

The latter is just as it sounds. Made of buffalo hide, the praise drum is traditionally played by an audience member to express approval or disapproval of the singer’s skill. These days, the drum is played by a ca trù musician, creating a sharp, discordant sound that punctuates the singer’s verses.

The song plays on

Ca trù is not institutionalized – there’s no textbook or school that teaches the complicated singing style.It’s entirely passed on by oral and technical transmission from singer to student, a process that Van says takes three to 10 years. The trainee must learn up to 100 songs by heart before a teacher will grant her permission to sing before an audience.

After her Sunday performance – attended by an audience of four – Van says, quite matter-of-factly, that ca trù “will likely die” with her. From the courtyard, the unforgettable sounds of ca trù emanate onto the busy Hanoi street. A few passersby stop to listen.

Van performs every Sunday night at Dinh Kim Ngan, 44 Hàng Bạc, Hoàn Kiếm, Hanoi.