“If you have someone that you think is The One,” Bill Murray once said (in a homemade viral video taken at a stranger’s bachelor party he crashed), “travel all around the world, and go to places that are hard to go to and hard to get out of. And if when you come back … and you’re still in love with that person, get married at the airport.”

That’s exactly what my fiancée, Kate, and I were doing one snowy night 16 years ago, when a car swerved into our lane on a rural highway in Poland.

We pinballed off the center guard rail, spun across three lanes of traffic, lurched off a 10-foot embankment and slid to a stop in a dark, snow-filled field. Upon landing, all the doors opened and anything that was not in a seat belt flew into the dark night, leaving us stunned in a crumpled car in eerie silence.

We were halfway through a two-year journey that began when Kate was offered a fellowship in Thailand just one month into our courtship. I followed her overseas with the blessing of my boss at the time, who let me telecommute from Bangkok. “Love is the thing you revolve everything else around,” she told me.

And so we did, first traveling all over Southeast Asia and when the fellowship was up the following year we traveled to Mongolia, China, England (where we bought the car of our accident), Scotland, Ireland, Belgium and France. At the top of the Eiffel Tower I asked her to marry me and then we drove on through Spain, Morocco, Italy and Austria.

The day before the accident we emailed friends and family a selfie video of us holding steaming mugs of glühwein in Vienna while singing “We Wish You a Merry Christmas!”

Secret wishes

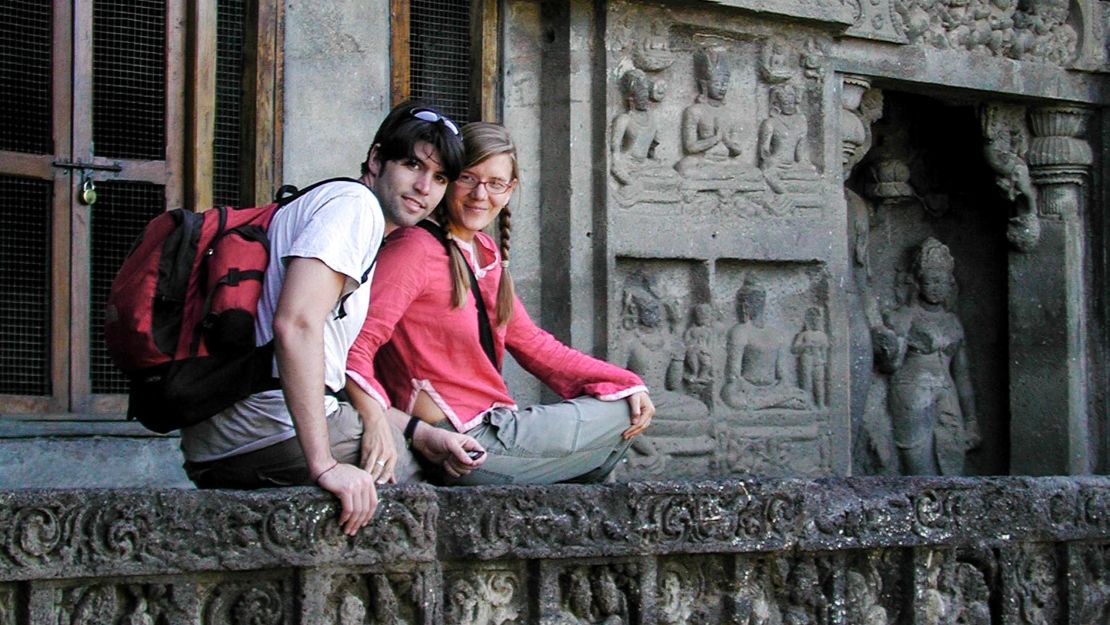

The trip was like our personal Wes Anderson movie oeuvre. The backdrops switched from urban to coastal to mountains. We skied the Alps, slept in yurts in Mongolia, traveled by train and worked at Gandhi’s former ashram in India.

We drank too much wine and absinthe in Spain, haggled over a rug in Marrakech, scrambled along the Great Wall of China and made secret, separate wishes for betrothal in a famous well at Macbeth’s castle.

“Travel is like love: It cracks you open, and so pushes you over the walls and low horizons that habits and defensiveness set up,” wrote the travel writer’s travel writer, Pico Iyer. Our isolation, plus the invigorating challenges that uncharted travel brings, was an effective vetting process for our relationship. That’s what Bill Murray was getting at.

Travel and being together nearly every day for a year let us kick the tires and check under the hood before buying.

We appreciated and appraised each other in situations we probably wouldn’t have faced had we stayed in San Francisco: aggressive touts, more aggressive food poisoning, non-aggressive pick pockets, getting lost, not speaking the language, falling off a horse, running out of oxygen in a scuba tank, drunk taxi drivers and a man who tried to sell us a stolen car and then left us deep in the suburbs of London, on foot. We laughed as he drove off and we realized what happened and then hopped on a random double-decker bus to a Tube station.

We were simply two young Americans without a fixed address or a dedicated itinerary for months on end, having the best time of our lives.

Until we had one of the worst.

Near death experience

We rarely drove at night. Waking up each morning and deciding what we wanted to do that day meant we never had to hurry. But on the day of the accident we had a planned rendezvous the next morning with friends in Krakow to visit the Auschwitz concentration camp together. The drive from Vienna took longer than we thought.

Kate anticipated the accident seconds before impact – not even enough time for an audible warning. We were in the fast lane but the driver who hit us was in the middle lane and driving faster. He would have passed us on the right except for a slow truck in his lane, which he didn’t see until he nearly rear-ended it.

We later learned he was texting on a cell phone. He looked up just before hitting the truck and jumped into our lane and hit us instead. He slammed our little black Citroen hatchback on the right, which was the driver’s side because it was British-born.

Once hit, I couldn’t hold the steering wheel straight. We ricocheted off the barrier and spun 360-degrees across three lanes of highway. We even passed in front of the unhurried truck driver that, in a Rube Goldberg way, had set off the accident.

In the universally accepted slow motion effect of near death experience, I recalled thinking that if another car hit us we would be killed. In those few seconds Kate gripped my shoulders and tried to pull us toward the middle of the vehicle to lessen the corporeal damage of another collision.

Instead of another hit we literally flew off the highway, over an embankment and through a fence. There was an elevator-dip-in-your-gut, Wile E Coyote fall as the car went airborne for a long moment, then landed with a sickening metallic crunch before tobogganing another 20 feet in the snow.

In the silence, we looked at one another and asked if we were ok. We were. And then we stumbled in a daze amid our belongings – strewn about the field like a haphazard yard sale from an unplanned eviction. Kate’s glasses were in the snow. Our backpacks catapulted more than 10 feet away. Windows were shattered, a tire was depilated of its rubber, the front bumper and lights were ripped off. The engine was seemingly untethered in the center of a crunched hood. Only we were left intact.

In her shock, Kate began gathering up teabags in the snow. She stopped. We embraced. And then we heard a voice from the top of the embankment. “Hello there,” a Polish accent called out, “Do you speak English?”

It came from the silhouette of a man at the edge of the highway. It was the driver who hit us. He helped us climb back up to the highway, introduced himself, and explained that he had called the police and an ambulance.

Emotional and vulnerable

While we waited for them he told us he had noticed our license plate about an hour earlier at the Czech-Polish border and thought two Brits in a French car were far from home. That we were Americans from San Francisco, by way of Bangkok and London, was even more puzzling.

For the rest of the night he was our chauffeur and translator as we went to the Auschwitz police station for paperwork, to a hospital to be examined for internal injuries (the ambulance never arrived at the scene), and then to a local junkyard where we made an emotional goodbye to our beloved car, which we had named Sophie. “It was just so violent,” I said to Kate as I touched it for the last time, holding back tears.

And although we weren’t seriously hurt – a fact confirmed in a dark, cold, creepy computerless hospital – we were shaken, sore, emotional and vulnerable.

At the police station I called the first American I’d spoken to in months – a confident young man who answered the after-hours emergency number of the Krakow consulate.

“Everything is going to be ok,” he said assuredly and assuring. “Tomorrow you’re going to come in to the consulate and we’ll take care of everything. Hand the phone to the police so I can talk to them and then I’ll tell you what they are doing.” I was so comforted by, and grateful for, his confident Americanness, I nearly cried again.

The next day an old college friend of Kate’s met us in the consulate waiting area. I shook Jesse’s hand just before Kate threw her arms around her friend and wept.

While Jesse and his new girlfriend Rebekah visited Auschwitz and the local sights for two days, Kate and I negotiated with the driver’s insurance company in a bespoke pidgin English, dodging bribes and unraveling legal issues based on baffling Iron Curtain logic.

A way out of the darkness

At night we met Jesse and Rebekah for dinners and drinking, accompanied by klezmer bands and candlelit bonhomie. A couple of days later they returned to the States and, having sorted out the insurance claim, we took a train to Prague to stay in Jesse’s apartment. We spent Christmas there, licking our wounds and staring at each other in the continued awe of being alive.

We were, that frightening December night, tested in a way we hadn’t been before. But the significance of the moment wasn’t immediately apparent to us.

On the night of the accident, from the safety of our pension hotel in Krakow, Kate called her mother to tell her we were okay, even though she hadn’t known we were ever in danger.

“How did you two handle it together?” she asked. At first Kate didn’t understand the question and her mother reminded Kate we’d recently gotten engaged. “How were you two together?”

“We were great, actually,” she told her.

From Prague we continued on to Amsterdam and India before flying back to San Francisco, buying a used van and driving our belongings to Washington DC. Nearly following Bill Murray’s advice, we were married within a few months.

Living and traveling extensively abroad, by ourselves – and maybe even almost getting killed – proved in hindsight to be the bedrock of what is now 15 years of a strong and happy marriage with two amazing children.

Kate and I speak each other’s language, negotiate marital turbulence, and agree on which route we’re headed. And when things get hard, we pull each other close to stay safe, we pick up the strewn pieces and then find our way out of the darkness together.

Love is the thing you revolve everything else around, and it doesn’t hurt to give it a good spin around the globe and into places that are hard to get out of, to see exactly what the relationship can withstand before you ride off into the sunset together.

David G. Allan is the editorial director of CNN Health and Wellness. He also writes “The Wisdom Project” about applying philosophy to our daily lives.