Editor’s Note: CNN Travel’s series often carry sponsorship originating from the countries and regions we profile. However, CNN retains full editorial control over all of its reports. Read the policy.

Even in the shadows of the Leang-Leang caves, the colors are surprisingly fresh: rich deep maroons, lightened by limestone.

With its bulging torso and spindly legs, the creature on the curving wall looks distorted. But it’s not. The painting depicts a babirusa, or pig-deer, a species unique to Sulawesi, Indonesia.

And the culture that created it made some of the oldest art on Earth.

The Maros-Pangkep karst region winds through more than 400 square kilometers of South Sulawesi.

Its tall towers, jagged cliffs and angular pinnacles are riddled with ancient caves. And, at least 39,900 years ago, human beings lived in these caves, and left their mark behind them.

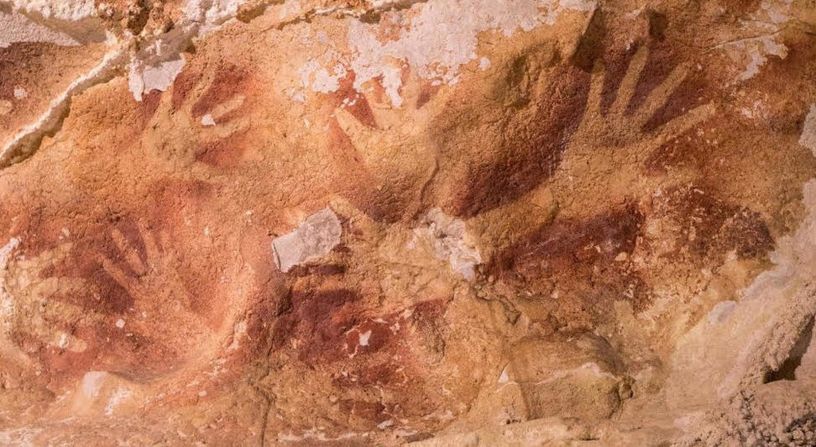

Sometimes, they made paint, sucked it into their mouths and sprayed it around their hands, leaving ghostly stencils – some child-size, some as large as a concert pianist’s, a few with missing fingers.

Other times they painted animals, typically pig-deer and wild pigs.

And they left their art in the entrance of the caves, in brightly lit spaces where, most likely, everyone could see them.

“The prehistoric caves are very important in the history of the cultural development of mankind, not only for the people who live in South Sulawesi but also for all humanity,” says Iwan Sumantri, an archeologist at Hasanuddin University in nearby Makassar.

That’s because creating art is one of the defining elements that make us human.

Until recently, many experts believed that art originated in Europe, around 35,000 years ago, in a mysterious flowering of creativity that would produce the celebrated paintings at Chauvet, France.

“The hand painting in Timpuseng, near Maros, has a minimum age of 39,900 years,” says Sumantri. That makes it the oldest known hand stencil on Earth.

A faded babirusa painting, also in Timpuseng, is at least 35,400 years old, placing it among the world’s oldest figurative art.

Sulawesi a former paradise, says archeologist

The Sulawesi paintings are dated by measuring the age of tiny stalactite-like growths that have formed over them, which yields a minimum age.

Most other dating methods produce a maximum age, so direct comparisons are difficult.

Adam Brumm, an archeologist at Australia’s Griffith University, is excavating in the Maros-Pangkep caves to try and learn more about the people who created this art.

“Sulawesi would have been a paradise for humans,” he says. “It’s a huge island. You get a great deal of variation, a huge range of habitats, it’s very rich in resources, and humans didn’t have a great deal to fear apart from other humans.”

Crammed together from two different continental landmasses, this sprawling, distorted island is still home to wildlife so plain bizarre that some naturalists consider it the Madagascar of Indonesia.

At the time these early artists worked, the largest predatory mammal was only a bit bigger than a modern house cat. The biggest natural threat to humans in Sulawesi’s warm, tropical climate was the giant python.

How much cave art exists?

While Brumm’s research is still in the early stages, he’s already beginning to build a picture of how the Maros-Pangkep people lived.

“Generally, you’re dealing with very small, highly mobile hunter-gatherer populations, who’d have moved round frequently from site to site and spent most of their time out in the forest rather than in the caves themselves,” he says, speculating that they mainly used the caves during the rainy season.

Where they got their materials remains a mystery. “We have not yet managed to track down the source of the red ocher,” Brumm says.

“It doesn’t seem to have been local. Possibly it came through trading networks with other hunter-gatherer groups located further inland.”

It’s not yet known how much rock art exists in the Maros-Pangkep karst region as many of the caves remain unexplored.

In fact, as we drive from the Leang-Leang cave art park, where a museum is set to open in 2017 or 2018, to the Rammang-Rammang karst zone, an explosion rumbles through the hills.

Many of the caves are protected by law, and some are tourist destinations – an area named Bantimurung is home to a butterfly park, while hornbills nest above a flooded cave in Pangkep.

But some unprotected areas are actively being dynamited for cement, a central driver of the economy in this developing region.

“It’s a problem,” Sumantri says simply.

“I was here”

At Rammang-Rammang, we pick up a little boat at a jetty, where enterprising locals are renting sunhats for a few cents apiece.

A staggeringly beautiful ride brings us through shady palms, under natural bridges, through dramatic karst gorges, to a simple farmhouse set amid the rice paddies.

Here we eat chicken curry, rice, fresh vegetables and sticky cakes.

Up in the karst above, an unnerving scramble through a narrow cave lined with sculptural stalactites and stalagmites brings us to the edge of a teetering void.

Our guide shines her headlamp down, revealing the brilliant blue of an underground river just below us.

Did these ancient artists see this view, I wonder? Close to the entrance, an ocher hand stencil rests high in the rock. I clamber up to look.

It’s hard to believe that, tens of thousands of years ago, someone came here and left this simple human sign that still reads clearly “I was here.”

Countless generations on, in a world where human ingenuity has put a man on the moon and set its sights on Mars, that message endures.

14 of Bali’s most enticing beaches

Getting there

The Maros-Pangkep karst region is near Makassar, in South Sulawesi.

Makassar’s Sultan Hasanuddin international airport, also known as Ujung Pandang (UPG), has direct flights from Kuala Lumpur, Singapore and all over Indonesia.

Plentiful buses to Maros stop outside the Leang-Leang cave art park. To reach Rammang-Rammang, hire a car or contact local tour operators such as Caraka TravelIndo.

Freelance guides can arrange multiday treks. The very oldest dated paintings, in Leang Timpuseng, are closed to casual visitors.

Theodora Sutcliffe is a freelance writer and occasionally photographer: she writes about diving, culture, adventure, food and cocktails, with a focus on Indonesia and China.