In the middle of the Atlantic Ocean, between South America and Africa, lies the island of St. Helena.

Sitting 1,200 miles west of Windhoek, in Namibia, it’s one of the most remote places in the world: a 46 square mile island of dazzling cliff walks, breath-catching drives, and swirling flax plants rippling in the ocean-whipped wind.

With a population of under 5,000, sometimes it feels like there are more dolphins in the ocean around the island than Saints, as the islanders are called.

Yet despite its remoteness, St. Helena is known all over the world for its most famous visitor, who died there 200 years ago.

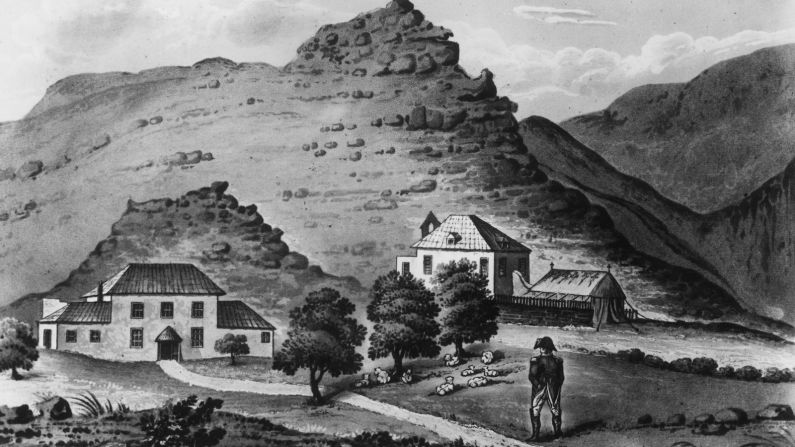

Napoleon Bonaparte – the first emperor of France, and conqueror of much of Europe – died at his home, Longwood House, on May 5, 1821.

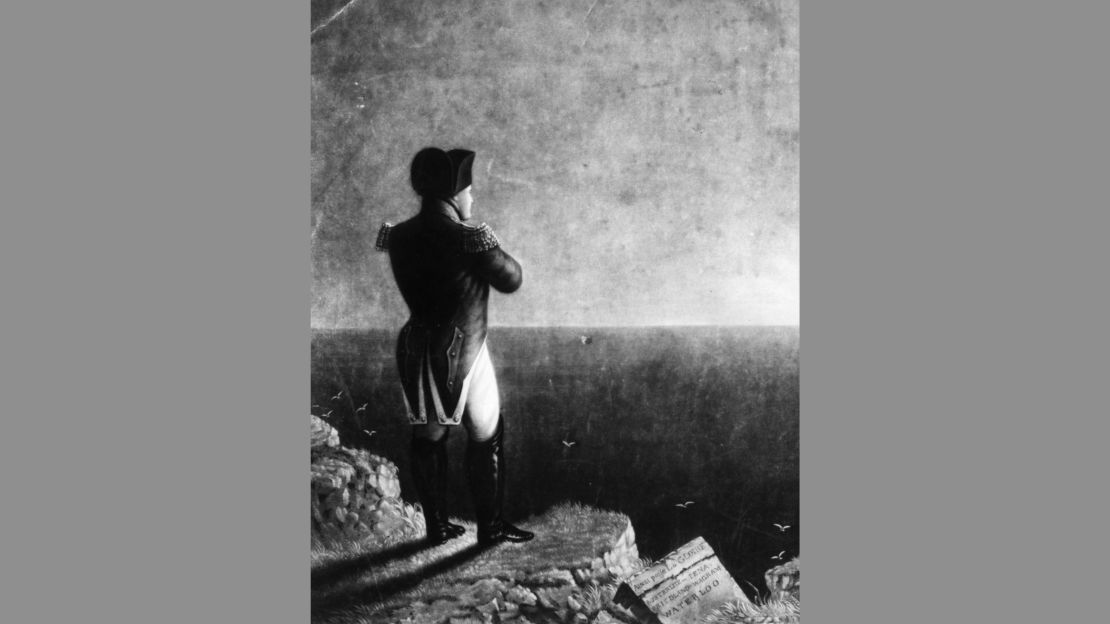

Not that it was his home by choice. Napoleon had been exiled to St. Helena after he was defeated by the British at the Battle of Waterloo in 1815. Having escaped his previous exile from Elba, off the coast of Italy, the French emperor was a flight risk to his fellow European rulers who wanted rid of him. Enter St. Helena – a British colony 5,000 miles and a 10-week boat ride away from Europe.

Napoleon spent more than five years on the island, arriving in October 1815. It’s where he created his myth, dictated his memoirs and battled chronic pain from old battlefield injuries – and, possibly, fatal stomach cancer.

And, two centuries later, his myth still survives on the island, carefully tended to by one man: Michel Dancoisne-Martineau.

The 55-year-old from Picardy, France, first came here at the age of 18 and has rarely left the island since.

He’s adapted to a way of life very different from most. He leaves the island once a year; if he orders something from Europe, it takes longer to arrive in 2021 than Napoleon took to get there in 1815.

And if you assume he’s doing it in homage to Napoleon, think again.

A different kind of legacy

Purchased from the British by Napoleon III, the first emperor’s nephew, the Napoleonic sites on St. Helena lie in stark contrast to their counterparts in Paris.

Instead of the Tuileries Gardens of the French capital, St. Helena has the gardens of Longwood House, his longterm home, which provide an ocean of color on this stark island.

Instead of the Malmaison chateau, St. Helena has the Briars, the sunny little cottage where he started his exile.

And instead of the extravagance of his tomb at Les Invalides, St. Helena is home to Napoleon’s original burial site. The emperor was buried on a lush hillside here, until France reclaimed his body 19 years after his death. Today, just a slab of stone remains, surrounded by black painted railings.

An airport at the end of the Earth

Michel Dancoisne-Martineau looks after them all. As the director of the French Domains on St. Helena, and honorary French consul, his job is to conserve these three little Gallic pockets on an island which is still a British Overseas Territory.

That conservation has also meant serious renovation. When he arrived, the previous curator had left things to the mercy of the elements.

“The old presentation was much more towards how it was at the beginning of Napoleon’s stay – he let the trees grow very close to the house to make it look even darker than it was,” says Dancoisne-Martineau. “That was a choice, but it wasn’t subjective. I proposed that we try to get the house how it was when Napoleon died on 5 May 1821 – both the house and his garden.”

So over the years, he’s redone the woodwork and paint inside the house, and has reinstated the gardens that Napoleon delighted in outside. “You can see the birdcage, the Chinese pavilion, the ponds, grotto and sunken paths – it’s a pleasure on its own,” he says. Indeed, the garden bursting with color – which Napoleon planned himself, once he realized he wouldn’t be getting off the island – has turned one of St. Helena’s bleakest spots into one of its prettiest.

The myth of the martyr

Not everyone is thrilled by Dancoisne-Martineau’s efforts to doll up the sites however. For starters, a large part of the Napoleonic myth rests on the idea that the emperor lived in appalling conditions on the island.

“Napoleon used the miserable, dirty conditions at Longwood, and the bad weather, for his own benefit, to create himself a martyr,” says Dancoisne-Martineau, adding that the emperor intentionally aimed for Christ-like connotations in his memoirs, which he dictated while on the island.

In fact, the truth wasn’t that far off. Longwood – the house assigned to Napoleon – was “the worst place on the island,” says Dancoisne-Martineau. At 500 meters above sea level, it was constantly wreathed in clouds and buffeted by trade winds. (Not that that was why the English assigned him the house – they put him there because, on a high plateau accessed via a switchback ridge, it was almost impossible to escape from.)

His exile had been arranged in such haste that nothing was ready for him when he arrived – even the governance of the island had to be transferred from the East India Company to the British crown. For the first two days, Napoleon was confined to the boat which had brought him to St. Helena, docked in the harbor.

And after two happy months at The Briars, a pretty cottage sitting above the island’s only major settlement, Jamestown, Longwood came as a shock.

“Slowly but surely he realized the terrible conditions, both of the weather and the house, which was falling to pieces,” says Dancoisne-Martineau.

“The wooden floors were rotten, the roof was leaking, there was water running through the walls, rats crawling through the planks, there was a smell of stagnant water under their feet – it was an awful place.”

Not only that, but the yearlong construction works building an accommodation block for his entourage next door created “noise pollution” on this most remote of islands.

And although the British promised to build him a new house, it was completed the week after he died.

Today, though, Longwood is a thoroughly gorgeous spot. Too gorgeous, in fact, for those who leave comments in the guestbook complaining that it’s just too nice.

“Some are disappointed that it isn’t dilapidated, as it’d fit with the legend of the very bad house – they’d rather see it ruined than well kept,” he says.

“But my job is to present you with the house of a man who died yesterday. I don’t have anything to prove.”

A legendary arrival

Dancoisne-Martineau’s own story is almost as fascinating as that of the man whose legend he burnishes.

Born in rural Picardy, in northern France, his journey to St. Helena reads like a novel. In 1985, as an 18-year-old student, he fell for the works of English poet Byron. Then he read a biography of Byron that was so good that he wrote to its author on the spot.

The author was one Gilbert Martineau – the retired curator of the Napoleon sites on St. Helena.

“He invited me to come for a summer holiday, and I was 18 and thought, that’s perfect,” he says.

Martineau was getting old. He’d already retired, but was still looking after the sites, as his job had been advertised for some time, but nobody had applied: “They couldn’t find someone crazy enough.”

Enter the young Michel.

“I fell in love with the island and decided to apply,” he says. At this point, he was studying agriculture – but this way, he could continue the course by correspondence, while getting paid for the upkeep of the Napoleonic sights. In short: “It was an ideal situation because I was broke.” He returned to France to do his compulsory national service, then signed up for three years in December 1987.

Dancoisne-Martineau hadn’t been happy in France: “I was rejected by my own family, so I had a big emptiness in my life.”

At the same time, Gilbert Martineau was feeling unfulfilled. Traumatized by his experiences in the French Navy during World War II, he had become “disillusioned with humanity,” says Michel, and retreated to St. Helena, which he hated – and took pleasure in hating.

But he also was an old-school man. “He had this notion that a man with no children is one who has wasted his life,” says Dancoise-Martineau. So, two years after their first meeting, he made the young man a proposal: he wanted to adopt him.

“He wanted a child to give importance to his legacy and name, and I was in need of a father figure, so we matched our interest and he adopted me,” he says, simply.

“He was the father I never had. I’m very proud of being his son – we had a normal father-son relationship for 10 years.”

So Michel Dancoisne, agriculture student, became Michel Dancoisne-Martineau, director of the French Domains of St. Helena and honorary French consul.

And his three-year tenure was extended again and again, as he bought land, built his own house, and then married a Saint.

He cared for Gilbert Martineau until the old man became ill with cancer, at which point they moved to La Rochelle, in France, for treatment. But once his adopted father died in 1995, Dancoisne-Martineau went straight back to St. Helena.

He has never left.

“The French man”

Today, “the French man,” as he’s known by the islanders, is one of the most famous residents of St. Helena. For curious visitors, a glimpse of Michel Dancoisne-Martineau – the man who renounced Europe to hole up on this remote island and tend to Napoleon’s memory – is up there with climbing the near-vertical, 900-foot Jacob’s Ladder in Jamestown, or hanging out with Jonathan, the 189-year-old giant tortoise, thought to be the world’s oldest living land animal, and resident at the (UK) governor’s mansion.

“It irritates me,” he says of the attention, adding that where islanders want to know all your business upfront, but then leave you alone, visitors have an insatiable need to catch a glimpse of him.

“I’m just doing my job, but for some reason people want to see me physically. Once I went to see a group because they were very insistent, but when I met them they had absolutely nothing to tell me – just wanted a photo. It’s almost as if they want to see the whale sharks, Jonathan, and me.”

And yet the life he has chosen is extraordinary to most of us. In 2017, the island’s much longed-for airport finally opened; before that, St. Helena was a five-day sail from Cape Town on the British Royal Mail ship, the RMS St. Helena.

Normally he leaves the island just once a year, but because of the pandemic, he hasn’t been off the rock for two years.

He buys just food on the island, stocking up on clothes and everything else on his annual trips to South Africa and France.

“If you want anything extra, like coffee or other things, you have to import them from the UK,” he says. Forget Amazon Prime; the delivery timeframe is three months.

And yet, he never wants to leave.

“I lived in a tiny village in Picardy so I’m used to a small community,” he says. “It’s not a challenge at all – it’s what I’m used to. And I love the community side of it. There’s this very strong feeling that everyone is there for everyone else. That’s why I love this place so much.

“I’ve built my house and married locally so I don’t have any reason to move away. And now, with Brexit, I feel more St. Helenian than ever.”

Myth and magic

So what about the man his life has revolved around for the past 34 years? Was he a legend or a monster? A great ruler or a cruel one? And, most importantly, was he murdered by the British, or did he die of stomach cancer?

Dancoisne-Martineau refuses to be drawn.

“You can believe Napoleon was a warmonger, a monster, a hero, a superhero – whatever you think about him, I really don’t care,” he says.

“I don’t have a strong opinion either way. It’s not my job to orientate the visitors – my job is to preserve, and to present you with the house of a man who died yesterday. If you hate him, you’ll be surprised that I’m not trying to change your mind at Longwood – I’m just putting the place into perspective.”

Familiarity has bred, if not contempt, disinterest in the subject.

“It’s my daily life so I lose perspective, objectivity, everything, just focusing on such a narrow angle of the man. Every piece of grass has its purpose for me.”

Not everyone is as relaxed. Although most visitors to the island come for its marine life and remote location, some are Napoleon fans – who are infuriated by the good condition of Longwood. Others try to steal the emperor’s possessions, which Dancoisne-Martineau has spent decades gradually recouping, after many were taken back to France or dispersed around the island.

And then there’s that empty tomb, located a 1 kilometer (0.6 mile) walk down a romantic, greenery-studded hillside.

“At the beginning I didn’t get it,” he admits. “I found it weird to become the guardian of an empty tomb. But it’s precisely because it’s an empty tomb that everyone has their own interpretation of the man.

“He’s no longer an individual; when an identity loses its physical substance it becomes a myth. And of course, a magical site [like the Valley of the Tomb] is ideal to illustrate a myth, and then nature does its own work to emphasize that myth. It’s where your imagination works. I love that.

“And it becomes very difficult to place Napoleon or define him, because everyone has their own approach. It’s amazing the amount of people who have interest, hate, dislike, love or passion about the man. It’s almost as if there are as many readings as there are people.”

That sweet island life

St. Helena is famously one of 14 British Overseas Territories, and was declared part of the British Empire in 1875. Although the UK’s former Colonial Office was abolished in 1966, Dancoisne-Martineau says that when he arrived 19 years later, there was still a “very strong” colonial feel to the place, with many civil servants on the island who’d been part of the old system.

“Slowly it vanished and colonialism disappeared,” he says, citing 1982’s Falklands War as one of the springboards for change.

‘“Then St. Helena took over control of its own destiny slowly but surely. It’s difficult because the island doesn’t have resources, so they’re dependent on the UK. It’s not easy but they have a strong will to claim ownership of their identity, which is very beautiful.”

But even during those early days, he said he never experienced hostility because of his nationality – despite generations of French-British antagonism.

“That passed away a long, long time ago,” he says. “The only times I’ve been attacked, and they’re so rare as to be almost marginal, have been by intellectuals in London still dictating to the island what they should think or do – postcolonialism.

“Locally, I’m just ‘The Frenchman’.”

Although, after spending longer on St. Helena than he ever did in France, he’s not your typical “Frenchman” anymore.

“I’m something in between,” he says, when asked if he feels more Saint than French.

“The French have a saying – ‘citoyen d’autre mer’ [citizen from across the sea], or ‘citoyen ultra-marin,’ which is even more romantic.”

Although he claims neither to like or dislike Napoleon, he admits to being “fascinated” by this man who “never gave up.”

“Most people in his position would be depressed and bitter, but he was resilient, a fighter, a man who never, never gave up,” he says.

But it’s St. Helena itself, rather than its most famous resident, that he feels closest to.

“I’m in love with the island and its people,” he says.

“This is the home I’ve been looking for all my life.”