Robbinroger Beever was 15 years old and walking home along a beach in Liberia, West Africa.

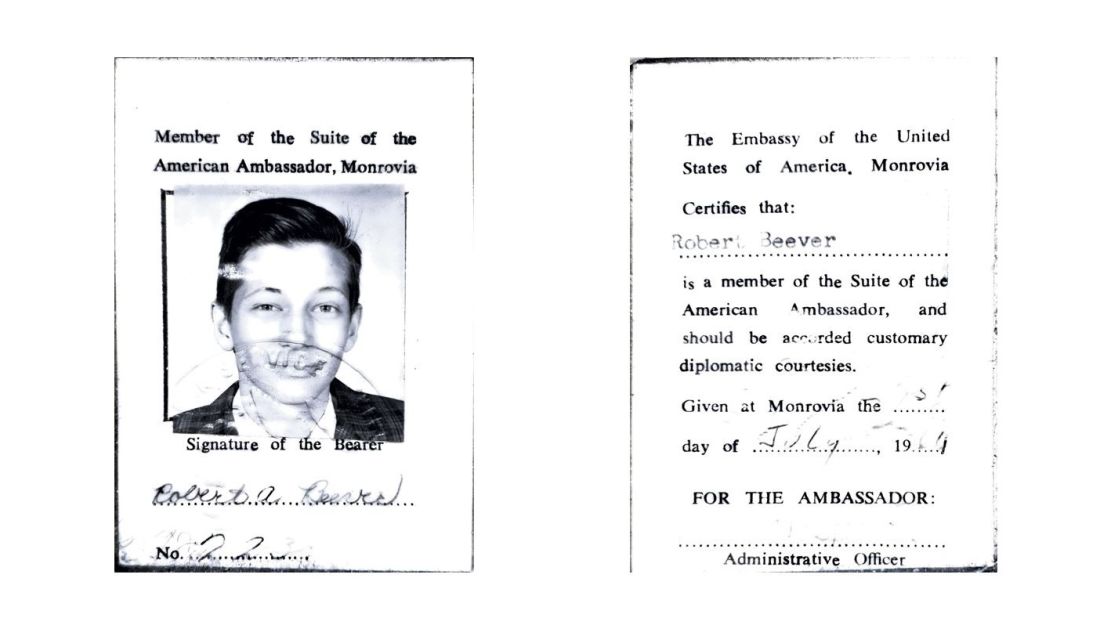

The year was 1967. Beever’s family lived near Monrovia, where his diplomat father worked at the US Embassy.

It was high tide and the sea had washed up seaweed and planks of wood and strewn them across the beach. Amid the debris, Beever spotted something glistening in the late afternoon sun.

“I’m the type of person who’s very curious about what the ocean can bring to people who have their eyes open,” he tells CNN Travel.

Beever got closer. It was a whiskey bottle. Picking it up, he could see something coiled inside. He tried to open the bottle, unsuccessfully.

It’s probably just some kind of label, Beever thought, but decided to take it home anyway.

Back home, he showed the discovery to his mother. They put it on the dining room table and after a bit of effort they managed to prise the cap open.

The something inside wasn’t a label. It was a letter – a message in a bottle.

Beever uncoiled the sheet of paper, and started to read:

“I threw this bottle off a merchant marine ship passing over the Equator near central Africa,” it read. “My name is Gösta Mårtensson, I am Swedish merchant marine.”

The letter was dated from 1965. Mårtensson had included a return address for his home in in Gothenburg, Sweden.

Beever enthusiastically wrote back, introducing himself: an American teenager, one of two sons of a British-American father and an Austro-Hungarian-Dalmation mother from Trieste, Italy. He told Mårtensson the story of how he’d stumbled across the bottle.

Mårtensson was thrilled his letter had found its way to a recipient, but he was in his late 20s.

I’m not the ideal pen pal for a 15-year-old, he thought.

But he had an idea: he’d introduce this young letter writer to his wife’s sister, Saija Kuparinen.

Kuparinen, 14, lived in Finland. She’d had no idea her brother-in-law had thrown a bottle off a ship near the Equator, but upon hearing the story she was eager to write to the boy in Liberia.

Kuparinen wasn’t confident writing in English, so she composed a message in German, writing about her school, friends, family and life in Finland.

She hoped she’d get a response, but her letter traveling across the world felt like a longshot.

But it wasn’t. Beever got her letter and was delighted. He loved the idea of communicating with a girl in Finland.

He scrawled a response, and a connection was formed.

Five decades later, the pair are still in touch, not only pen pals but close friends who’ve watched each other grow up from afar.

Today, Kuparinen lives with her family in Finland, while Beever, who’s spent time in countries across the globe, now lives with his wife and sons in Germany.

“Our friendship never stopped, even when I had my life with my daughter and husband,” Kuparinen tells CNN Travel.

“We have been corresponding for almost 55 years – from being giggly teenagers to older responsible adults,” says Beever.

“I felt really, really connected to her.”

A globe-spanning friendship

Growing up, Beever’s family were never in one place for long.

Following the three-year stint in Liberia, the family moved back to Washington, DC for a year. For a while, Beever’s letters to Kuparinen came with a US post stamp.

He wrote in English, and, at first, she always wrote back in German.

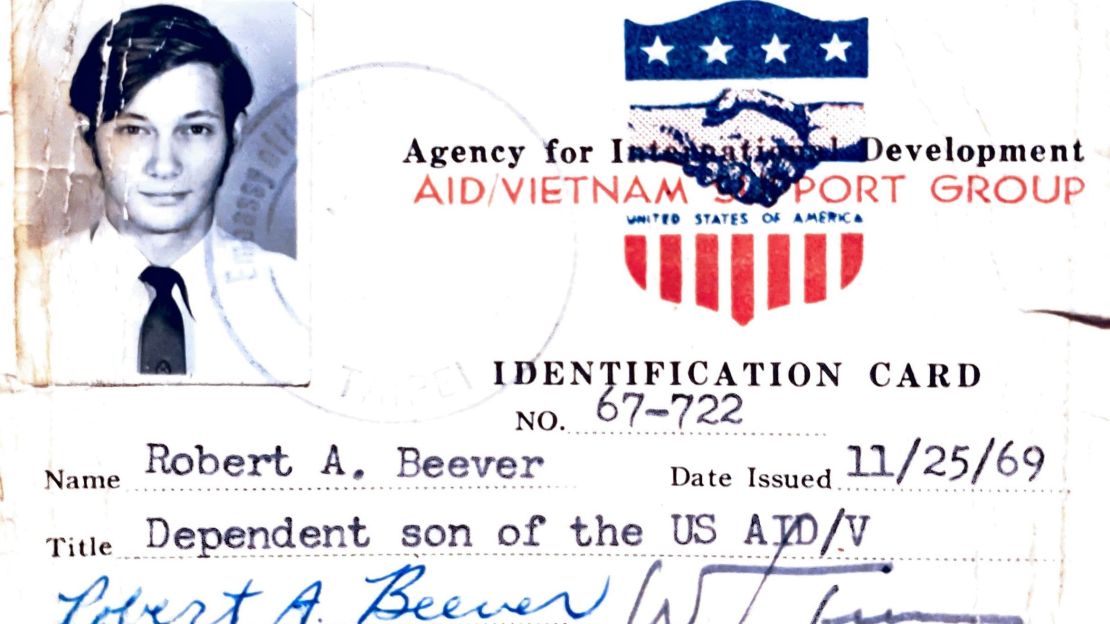

Then his father started working for the US Agency for International Development and was dispatched to Vietnam to work as an advisor during the war. His wife and sons based themselves in Taipei to remain a safe distance from the conflict.

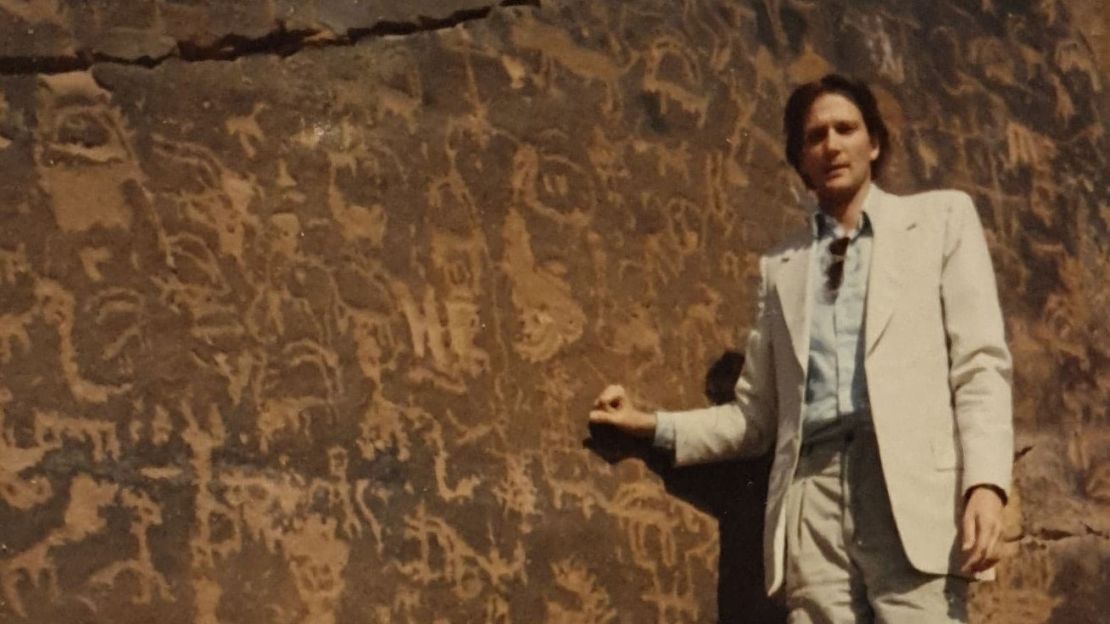

Beever wrote to Kuparinen about his growing love of Taiwan, especially the folk art tradition.

He also wrote candidly about his worries for the future.

“We were growing up. We don’t know what direction our lives will go in. The Vietnam War was raging,” he says.

“I always felt I could write to her. I had never met her, but I felt there was a kind of spiritual connection between us.”

Beever began traveling back and forth to Vietnam to visit his father, and he wrote to Kuparinen about what he saw.

“Some of the experiences were beautiful,” he says. “Others were horrendous, especially when I saw American soldiers, who were my age, fighting a war against people they didn’t understand, in the country they had very little information about.”

At 18, Beever had to register for the draft. Some of his American friends served, but his number was never called up. He was relieved.

Among these more serious musings, Beever and Kuparinen had also bonded over a love of rock music.

They were both fans of The Rolling Stones and The Mamas & the Papas. The pen pals started to speak on the phone on occasion. One of them would play a record through the receiver, and they’d dance together – separated by oceans and thousands of miles.

Already, Kuparinen had become a constant in Beever’s life. He’d always made friends easily but moving from place to place meant retaining those relationships was hard.

And for Kuparinen, receiving dispatches from countries she’d never been to was fascinating.

“Of course, in my youth others had pen pals too, but not the kind [like] Robbie, who was moving from one country to another,” she says.

Kuparinen always tried to make her responses creative and interesting. She used to make envelopes from pages she’d torn from fashion and nature magazines.

Receiving these, and seeing the care and attention behind them, was a thrill for Beever.

“Then I knew she really liked me, even though we had never met,” he says.

Growing up

As the two graduated into young adulthood and moved away from home, not every letter successfully made it to the recipient.

But whenever mail got waylaid, the pen pals would persevere until they got hold of the right address.

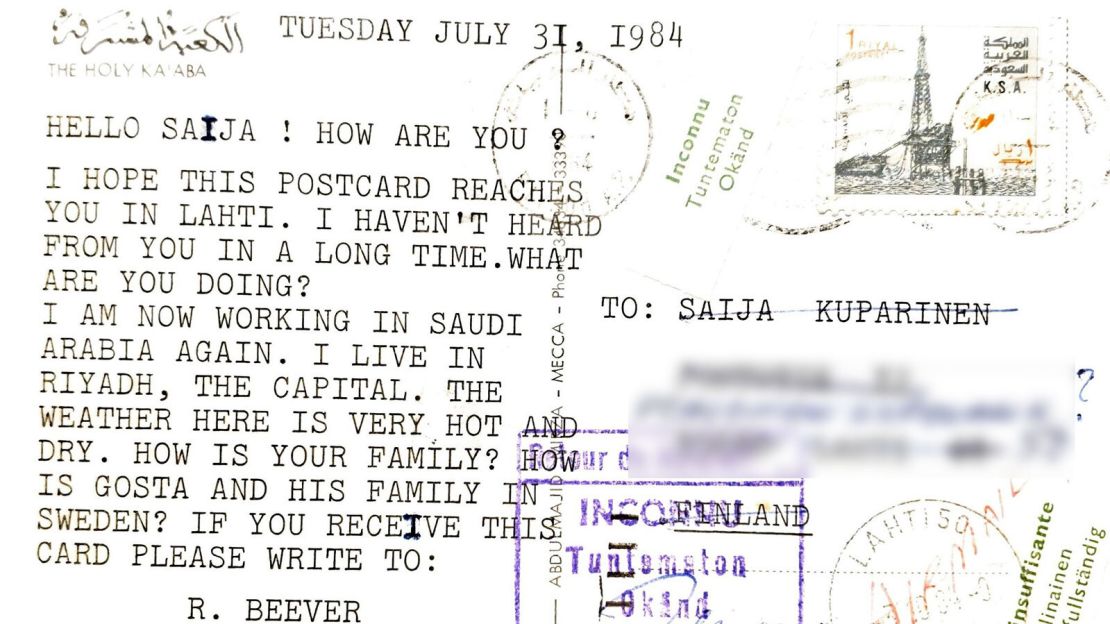

Beever continued to travel extensively into adulthood, working in Taiwan for a while, before taking a job in Saudi Arabia.

He still has a postcard he sent from Riyadh that was returned to sender.

“How is your family?” he wrote in the never-received dispatch. “Are Gösta and his family still in Sweden?”

Gösta Mårtensson, the merchant marine who’d kickstarted this letter-writing friendship, was delighted his sister-in-law and the finder of his message in a bottle had stayed in touch.

“He was very happy and interested in it,” says Kuparinen.

Years passed. Their lives continued to move on, but the correspondence continued.

When Beever met new people and told them about his friendship with Kuparinen, he referred to her as one of his best friends.

He reckons the physical distance between them helped the emotional closeness.

“It gave me reflection time when I was writing,” he says.

“Sometimes she asked me very deep philosophical questions: Where do you think you will be in 10 years? Are you married yet? What are you doing now? Do you still have wanderlust? When are you coming to Finland to visit us, we’ve been writing for so long?”

With the dawn of the internet age, the duo began interspersing their snail mail with emails.

Sending links to music they loved was easier, and attaching photographs was a bonus.

And a long-awaited in-person meeting was finally planned.

Meeting after 35 years

Kuparinen met Beever for the first time in person in 2003, at Helsinki Airport. She greeted him with her husband and daughter in tow.

At first it was surreal – none of them was quite sure what to say. They introduced themselves. Rather formally, the pen pals shook hands.

“I’m Rob,” he said.

“I’m Saija,” she replied.

They got in the car and drove to Kuparinen’s home.

“She invited me in, and she said, ‘Rob, I’m happy you’re here,’” recalls Beever. “We had some coffee and some cake, and things got much better after that.”

As for Kuparinen, she says she truly didn’t believe Beever would actually visit until she saw him in person.

It wasn’t that she didn’t trust his word, it’s just the meeting was so long anticipated that it was hard to believe it was finally occurring.

Talking in person turned out to be just as natural as their years communicating by mail.

“It was like we had [been] speaking all the time,” she says. “We were so special friends. We just continued in real life.”

The visit was characterized by walks along the coast, searching for the midnight sun and long chats over hot coffee.

Kuparinen’s daughter and her husband quickly fell into an easy camaraderie with Beever too, cooking him a traditional Finnish meal and showing him how to enjoy a Finnish sauna.

“We all liked this big American man a lot!” says Kuparinen.

“it was a very nice time together, I could feel the positive energy,” says Beever.

After the visit came to an end, Beever said his goodbyes. Back home, he got a call from Kuparinen.

He’d accidentally left behind a sweater.

She said, “Let me keep it here, so you have to come back.”

Over a decade later, Beever visited Kuparinen for the second time. More time had passed, he was married with two twin boys. His family came along too.

It was a different experience, but just as special.

“We all got along very well together and that was lovely,” says Beever. “We went mushroom picking, we went berry picking.”

At the end of the day, the families would unwind with a Finnish beer, reflecting on their lives and Beever and Kuparinen’s friendship.

Reflecting on friendship

In recent years, the two friends have switched to video calling. They still occasionally send physical letters in the mail, but email has become the default.

“I think something has been lost and gained at the same time,” says Beever.

Email and video call are immediate, easy, he says. But there’s something magical about snail mail.

“There’s nothing more exciting than to receive a letter in a beautiful envelope, nicely folded, with birds and flowers, and open it. And actually, it’s a part of the person that comes.”

This past year, grounded at home in Germany in the wake of the pandemic, Beever started properly sorting through the piles of letters, ID cards, souvenirs and momentos from his life, stored in his garage.

It’s a treasure trove of memories, and they’re all tied up in his friendship with Kuparinen.

“I look at the addresses and I read the things that we did 40 years ago, she in Finland and me in one of a dozen countries I was in, and it’s just something I really enjoy,” he says.

“It gives me time for reflection, how much I’ve lived, how far we’ve come in life. And also, the realization that there’s more behind us than in front of us. So, live for the moment, and share your love with your family and friends and really show them that.”

“I often think about our history,” says Kuparinen.

She doesn’t have all her letters anymore – some have got lost along the way. But the memories remain.

“We shall stay good friends on and on and on.”