Story highlights

Great Zimbabwe was the capital of a trading empire and home to 10,000 people in the 1400s

Zimbabwe is making a tourism comeback after hitting rock bottom in 2008

Visitors have yet to rediscover Great Zimbabwe, however, leaving it almost deserted

About halfway up the cobblestone stairwell, the screeching starts.

Loose stones tumble from the tops of the walls far up on the hilltop.

All around me, tree limbs shake.

It’s just after dawn, and I’m alone, climbing the trail to the 15th-century royal compound on the hilltop at Great Zimbabwe in southern Africa.

Alone, except for the baboons.

Like all the stone structures here, the stairwell is open to the sky, but the incline is so steep and the curves so sharp that I can’t see more than 10 feet in front of me.

Sure enough, around the next bend a baboon is waiting for me on one of the dozens of terraces that skirt the hillside.

We watch each other for a few moments until I’m certain he’s not interested in me, and then I keep walking.

Baboons freak me out, but these moments are part of what makes Great Zimbabwe such an incredible place to visit.

Baboon standoffs

Unlike the world’s more visited ruins – which is basically every other ruin – here it’s easy to lose yourself in the mystery of the place, even if that means the occasional standoff with a baboon.

The stairwell leads to a narrow passage through a cleft in the rocky hilltop. Stone walls that form the perimeter of the royal complex tower overhead.

They once would’ve extended even farther out over the stairs, but a terrace collapsed since the city was abandoned, bringing a wall down with it.

It’s hard to find a vantage point to see the entire complex.

The old city, which was the capital of a trading empire and home to 10,000 people in the 1400s, stretches over 1,800 acres.

Essentially the hilltop functioned as a palace and cathedral, the center of political and religious power.

On the planes below, circular stone walls form a series of enclosures.

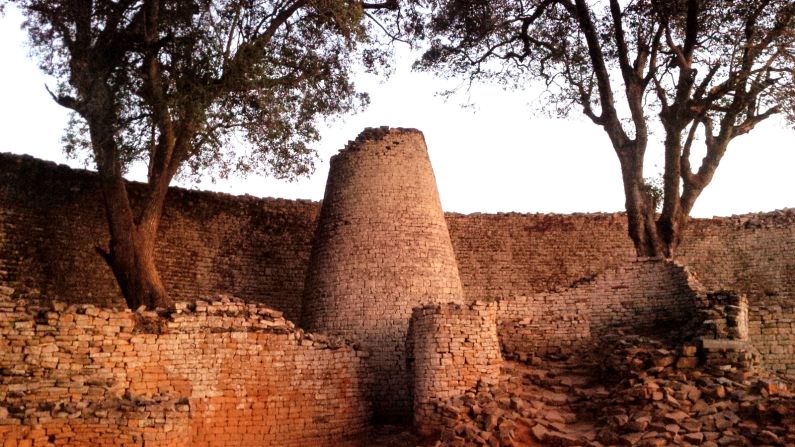

The most iconic, aptly called the Great Enclosure, is the largest pre-colonial structure south of the Sahara. The walls rise up 36 feet and stretch 820 feet around.

At one end, an inner wall forms a narrow passage that leads to a conical tower, the most distinctive landmark in the old city.

I like the hill complex more.

Here the walls curve around each other and the granite boulders, which are incorporated into the design. Different chambers are linked by a labyrinth of narrow passages that snake up and down over the giant rocks.

At the far side is a chamber with a towering stone ledge that once held a small stone wall that acted like a balustrade.

Destructive treasure hunters

Like all the structures here, the stones were assembled without mortar.

Each layer was slightly recessed, creating a slope that held it all together. Over the centuries, some walls were knocked down by treasure hunters, or just by the elements.

The chamber below is where a famous set of carved birds were found.

Most of them are now housed in a small museum inside the park, which is worth a visit if only to see them.

The image of a bird appears on the national flag, and is as much a symbol of Zimbabwe’s national identity as the Statue of Liberty is to the United States.

There’s a good chance of being here alone.

Visitors might see schoolchildren passing through on their way to class, or the occasional park worker, but not many other visitors.

Tourism in Zimbabwe has been in a long and slow recovery.

In the 1990s, Zimbabwe was for a moment the most visited country in sub-Saharan Africa.

By the time the nation hit rock bottom in 2008, hardly any foreign visitors came.

Now major attractions like Victoria Falls are bouncing back, but places like Great Zimbabwe have fallen far off the radar.

The ruins are easily accessible by road, but it takes several hours from Harare or a full day from Johannesburg, so not many people make the effort.

But this is a place I love returning to.

Expert tours

In the colonial days when Zimbabwe was known as Rhodesia, white families used to vacation here, and remnants of those days remain.

The national park has simple rondavel huts for hire, and there’s the dated but charming Great Zimbabwe Hotel (Great Zimbabwe, Masvingo; +263 39 262274) just outside the gates, as well as the posher safari-style Lodge at the Ancient City (No 1 shephared Plot, Great Zimbabwe, Masvingo; +1 888 790 5264).

The inn’s restaurant – where the buffet is designed like the stone walls – serves lucky travelers fresh bream from the nearby dam.

If not, there’s almost always a fisherman selling his catch on the roadside, which can be grilled outdoors – or ask the restaurant to prepare it.

On my latest trip, I went with an excursion organized by The Wits School of Arts at the University of the Witwatersrand in Johannesburg.

Those going on their own can hire a guide on site.

Every guide I’ve ever had here has been articulate and charming and well-informed, but it’s even more amazing to spend a few days exploring the ruins with people who actually wrote the book on Great Zimbabwe.

You can find their offerings at wsoa.wits.ac.za, under History of Art.

Practical tips: Zimbabwe has started an online visa system (www.evisa.gov.zw/), which isn’t working at the time of this writing. When it does, applying online will get visitors a letter that they must present on arrival, which is when the visa is actually issued.

Those that require a visa might be better off simply getting it on arrival.

Anyone driving up from South Africa can save themselves a lot of hassle at the border by contacting the Zimbabwe Tourism Authority ahead of time. They can arrange to have an officer to wait at the border post and walk visitors through the immigration and customs process. This can save hours and endless headaches. And it’s a free service (Lindarose Ntuli at +263 772 409373 or lindarosentuli@gmail.com).

Griffin Shea is a writer and traveler based in South Africa. His latest project is a travel app for African cities for iPhone and Android.