Possums, a baby armadillo, two deer, the sounds of owls and other birds.

Siblings Flynn and Hannah Dunnuck spotted so many animals during their camping trip on Cumberland Island. So did their friends, siblings Lucy and Riley Peltz.

“We found like 40 crabs,” said one.

“We found these little clams,” said another.

“We saw a bunch of horses.”

And the list went on and on, as the four kids recounted their adventures animal spotting, biking, swimming and hiking all over the island during their six-day camping trip with their parents.

The Dunnuck and Peltz families of Asheville, North Carolina, reserved their campsites months before they traveled to Cumberland Island National Seashore, which features a barrier island off the coast of Georgia.

The families have camped on the island for several years, so they know to reserve their campsite in advance. The park’s current management plan allows the park ferry to bring no more than 300 people to the island each day.

That means that ferry rides and campsites for the high seasons, which include March through April, October and holiday weekends, can sell out quickly.

“We like to hike around and explore, look for shark’s teeth, have a lazy play day on the beach, do trail hikes,” said Erin Dunnuck, Flynn and Hannah’s mother. “You always see different animals every year.”

“Rather than see condos and gold courses, it’s unique to have wilderness beside the beach,” she said. “That minimizes the trash and wear and tear on the island.”

An island buffeted by nature

For the most part, those families are seeing a barrier island ruled by nature. Last year’s Hurricane Irma knocked out the National Park Service pier at the mainland town of St. Marys, while Hurricane Matthew knocked out two island piers in 2016. One of those island piers was partially repaired for the park ferry to still dock there.

Post-Irma last year, St. Marys and the National Park Service quickly worked out a deal to renovate the city pier for use by the park service just two months after the hurricane hit.

While most of Cumberland Island became a national seashore in 1972, there are still private landowners living on the island who own their land outright. Other owners have negotiated to keep their land for a certain length of time or until they have passed away.

While there’s plenty of heated debate about the possibility of new housing being constructed on the island’s privately-held land, visitors continue to visit the island. They will only see those few hundred other visitors, longtime residents and National Park Service employees and contractors.

Park service staff are split between those who work with visitors, those who protect historic structures and objects, and those who work in nature, entrusted to care for species and other flora and fauna on the island.

Protecting the sea turtles and more

The group includes wildlife biologist Doug Hoffman, whose job includes protecting loggerhead sea turtles from predators.

“The island has a wide diversity of wildlife and resources to see,” said Hoffman. “There’s a wide range of wildlife and plants, and just the different habitat types. There’s over 20 vegetative communities (and) 18 plus miles of beach habitat.”

Hoffman, who has an encyclopedic knowledge of the island’s geological and human history, isn’t just responsible for the sea loggerhead turtles, which are listed as threatened under the Endangered Species Act. He’s also responsible for year-round feral hog control, feral horse population monitoring, shorebird monitoring, protecting shorebird nesting, wildland fire response and facilitating scientific research projects in the park.

“We have documented over 500 plant species, over 300 bird species,” plus 30 mammal species and 55 different types of reptiles and amphibians, said Hoffman.

Hoffman is often out late at night, tracking wild boar (abandoned by residents long ago when they left the island) and other predators who like to attack seat turtle nests. During nesting season from mid-April to mid-October, he supervises a crew of three to monitor the beach for nests.

Friendly human visitors might spot a live sea turtle “when they go to the beach in the morning in the summer time, or they quite possibly could see a turtle nest hatch late at night – if they’re that ambitious to go out and sit next to a nest and watch it,” said Hoffman.

Humans have lived here for centuries

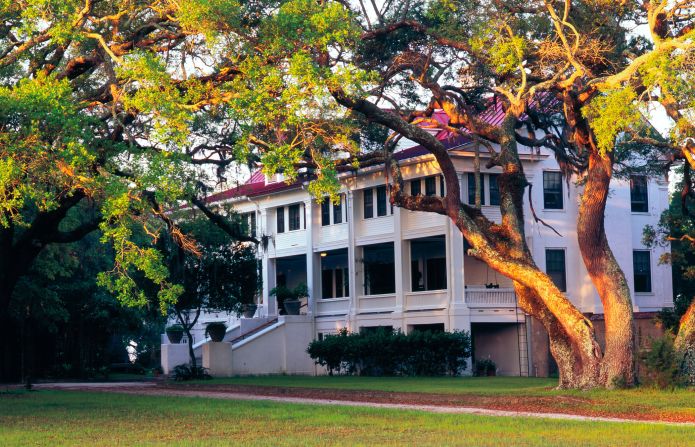

Or they might stumble onto what’s left of one Carnegie mansion, Dungeness Ruins; another Carnegie mansion still standing, Plum Orchard; and First African Baptist Church.

While those buildings date back to the late 1800s, there’s a history of human habitation on the island that goes back thousands for years.

The island has been home to the Timucua Indians since before the Spanish colonized the island in the 16th century, followed by the British and later the United States. (Different Timucua tribes lived on island from present-day Southeast Georgia to Northeast Florida.)

Colonists established plantations on the island prior to the founding of the United States and forced enslaved African-Americans to work the land. After the Civil War, the Carnegies and other families bought land and built homes.

African-American life on the island

The island’s modest First African Baptist Church is well known for hosting the wedding of the late John F. Kennedy Jr. and Carolyn Bessette.

However, it’s more well known in the history of Cumberland Island as the heart of the Settlement community – the free African-American community that grew out of slavery, said Jill Hamilton-Anderson, the seashore’s chief of interpretation, education and visitor services.

Where once they were forced to work the land, many of these then-free people congregated in communities around the island after the Civil War, including the community anchored by this church at the island’s northern end.

The first church was established by Primus and Amanda Mitchell, who stayed on the island after they were freed.

“This was a place for worship, this was a place for education. It’s what really connected the community,” said Hamilton-Anderson.

Beulah Alberty, the granddaughter of Primus and Amanda Mitchell, became “the matriarch of this community,” she said, noting that Alberty’s home is still on site.

“She’s the one who helped to build the current church we’re in that was built in 1937,” which replaced the older log cabin church built in the 1890s.

No matter where you go, it’s quiet

Sitting in that empty church, a church where people still can get married, the quiet is impossible to ignore.

With a few hundred people on the island, the noise of human civilization mostly drops away. Instead people hear the sound of wild horses trotting by or owls hooting or feral hogs rustling nearby. Even the historic structures seem quiet, empty of the residents who once lived, worked and entertained there.

“A lot of the comments I’ve had from people is just the immenseness or the vastness of the forest that they see, or the lack of human related noise like automobiles or any type of industrial type noises,” said Hoffman.

“They don’t hear the typical day to day hustle and bustle that they hear when they’re in civilization,” he said. “When they get here, all they hear is the birds singing or the wind blowing.”

If you go: Visitors have two options if they want to stay on the island. They can book a campsite or stay at the elegant, all-inclusive Greyfield Inn, the only hotel on the island. Day trippers can book rooms at the hotels in St. Marys, the town where visitors get on the ferries to Cumberland, or further out on the mainland.