For photographer Allan Hailstone, 1950s Berlin had an irresistible attraction.

In the aftermath of World War II, it was “a city like nowhere else, with palpable atmosphere and decay,” writes Hailstone in his new book “Berlin in the Cold War: 1959-1966,” published by Amberley Books.

The photographer first visited the city in the late 1950s and he returned frequently in the decade that followed.

Wandering the city, the photographer-turned-flaneur captured candid snapshots of a city in flux – crossing from West to East, capturing Berlin’s dual sense of identity.

“It was such an interesting city. I just kept going back,” he tells CNN Travel.

Hailstone’s photographs form the backdrop of his new book, charting the effect of the Cold War division on the German city.

A city divided

Hailstone always had an eye for cityscapes.

“I was interested since about the age of 10 in taking street scenes. I started in my hometown of Coventry [in the West Midlands, England] and it just went on from there,” says Hailstone.

His fascination with Berlin began as a boy – he discovered a book about the city in his local library.

Some years later, as a young man, he arrived in the German metropolis to discover a city divided.

“When I first arrived in West Berlin, before they built the Berlin Wall, it was really like most Western cities,” reflects Hailstone.”It had advertisements and bright lights, although there were quite a lot of bomb sites.”

Crossing the border to the East, those streets told a different tale.

“When I walked into East Berlin, it had almost been left just as the war had left it,” Hailstone remembers. “There were photographs that I took, there’s one where there’s a whole pile of rubble in front of a church.”

Hailstone was also struck by aesthetic differences between the two halves: “In East Berlin, there weren’t any bright colors, it was all pale red, pastel shades.”

The evocative everyday

Hailstone’s photographs are evocative shots of the everyday – in an image from September 1959, a man reads a newspaper in a cafe by the border. In August 1960, East Berliners wait for a bus in front of a building adorned with Communist propaganda posters. In August 1962, West Berliners holiday in Wansee.

“I’d just wander around with a camera and see something and think ‘I’ll take that,’” says Hailstone.

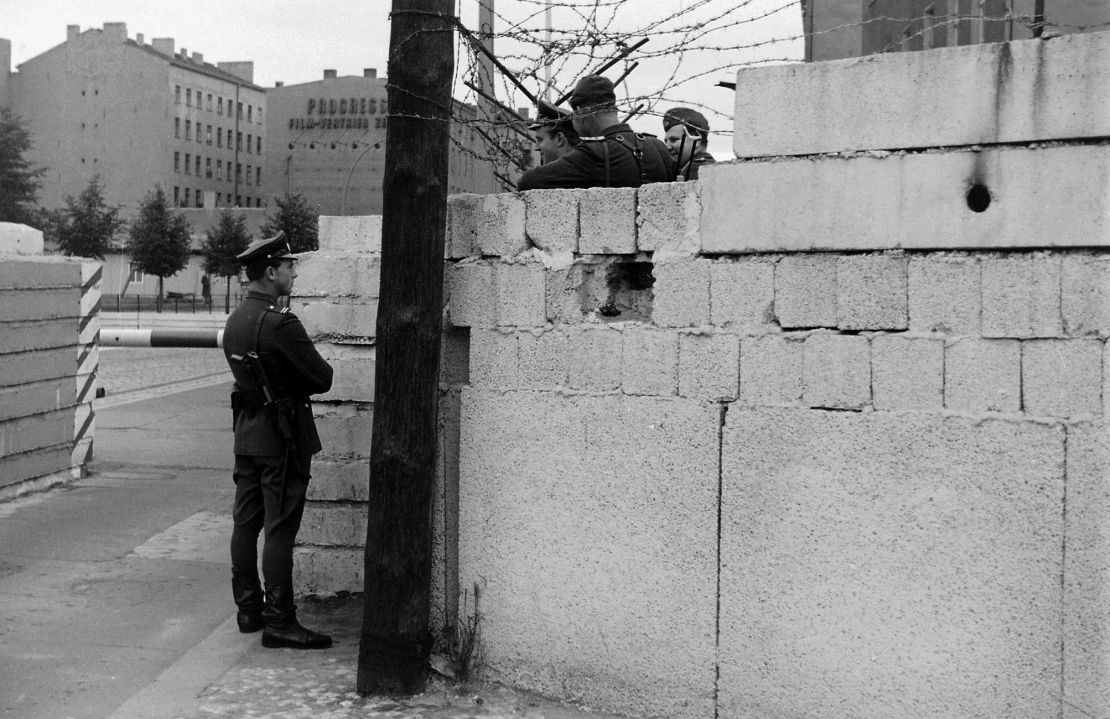

One of the stand-out images in the book is of a group of border guards sharing a joke at the Berlin Wall.

Taking photographs of East Berlin guards at the borders was a dangerous idea – but not for Hailstone, who was standing just inside West Berlin when he took the photograph.

“Of course I was standing technically in the West, so they couldn’t really do anything about that,” says Hailstone. “To take pictures from the Eastern side would be much more risky […] you’re asking for trouble.”

One of the remarkable aspects of Hailstone’s collection is that each photograph is labeled with an exact location and date – allowing the reader to appreciate the photographs in their historical context.

“I was always meticulous in taking the date down and where it was, the name of a street,” says Hailstone. “It’s proved quite useful to be able to do that, because you can now Google things like the street and find the history of it.”

It can offer some quirky insights too.

“In the film ‘Back to the Future,’ the character goes to a specific date [November 5, 1955] and I took quite a few pictures of London on that day,” says Hailstone. “It’s just one of those quirky things. Because I noted the date down, otherwise I’d have never have known that.”

The allure of Berlin

Over the past 60 years, Hailstone has photographed cities across the world – his celebrated shots of mid-century London were published in the volume “London: Portrait of a City 1950-1962.”

But Hailstone says there was something particularly intoxicating about Berlin.

“It’s funny how people get this feeling about the city, which I got to some extent, it’s a very interesting place, or it was,” he says.

“I don’t know whether it is so much now,” he adds. “It’s a lot more touristy now.”

Hailstone’s keen eye allows him to pinpoint scenes that should be photographed for posterity – and he is pleased that the book will serve as a historical record of a specific time and place.

“Wherever you are, I always think it’s more interesting […] to take pictures of things that are going to change,” he says.

![<strong>Unter den Linden, East Berlin, December 26, 1964</strong>: Thanks to Hailstone's keen eye, he has amassed a collection of evocative photographs of a bygone era. "Wherever you are, I always think it's more interesting [...] to take pictures of things that are going to change," he says.](https://media.cnn.com/api/v1/images/stellar/prod/170925113002-unter-den-linden-east-berlin-26-december-1964.jpg?q=w_2008,h_1301,x_0,y_0,c_fill/h_447)