A skull pokes out of a coffin made out of roughly hewn planks of wood, its smooth white surface catching the reflection of the winter light flooding into the dark cave.

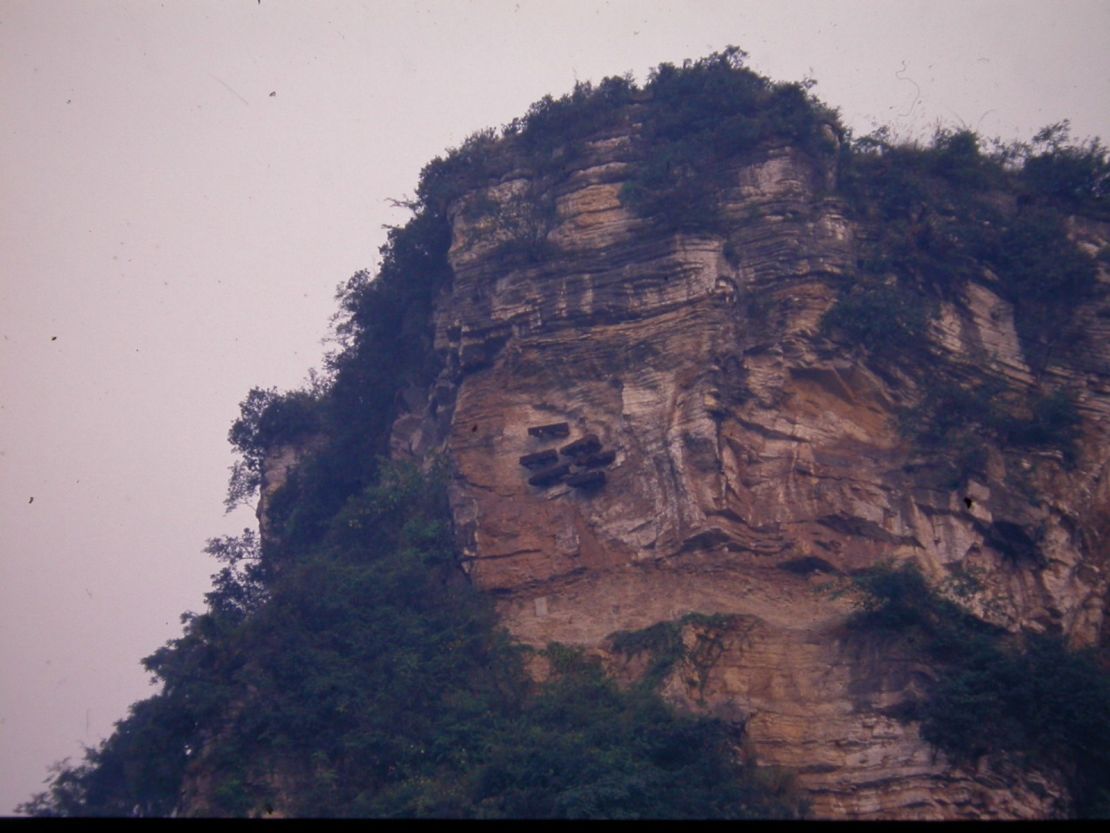

It’s one of about 30 caskets anchored on a limestone rock about 30 meters (almost 100 feet) up the side of a cave in Guizhou province in southwestern China. It could date back hundreds of years. The coffins, inside and out, are littered with fragments of clothes, bones and ceramics.

For three decades, Wong How Man, a Hong Kong-based explorer, has been hellbent on chasing coffins like these in gravity-defying graveyards across China in an attempt to discover more about this unusual burial custom.

Wong, who began his career as a journalist with National Geographic, first came across a group of coffins perched 90 meters (300 feet) up a cliff face in southern Sichuan, to the north of Guizhou, in 1985 during an expedition to track the Yangtze River from mouth to source.

A life-long obsession was born.

“At first, it was simply how the hell did they get there and then I couldn’t stop thinking about why,” he says. “And there’re so many theories.”

Coffin-chasing

Hanging coffins, as they’re known, are found across a swathe of central China – mostly in remote valleys to the south of the mighty Yangtze River, which flows from the Himalayan foothills to China’s eastern coast.

The coffins rest in a variety of formations, sometimes barely visible from the ground below. They’re lined up in the crevices in the cliff face, balanced on wooden cantilevered stakes, placed in rectangular spaces hewn in the rock face or stacked high up in caves like those Wong saw on his latest coffin-chasing expedition to Guizhou.

The oldest are said to be in the eastern province of Fujian, dating back 3,000 years. There’s no clear reason why this practice took place.

Ancient literature from the Tang Dynasty suggests that the higher the coffins were placed, the greater the show of filial piety to the deceased. Others say the reasoning was more practical: It prevented animals from poaching the bodies and kept land free to farm.

New sites are still being discovered. In 2015, the People’s Daily newspaper reported that a total of 131 hanging coffins were discovered in the central province of Hubei, placed in man made caves in a cliff 50 meters wide and 100 meters high.

“Experts haven’t figured out how ancient people managed to transport the coffin, body and funeral objects – together weighing hundreds of kilograms – to the cliff caves,” the report said.

Many questions, few answers

Intent on discovering more about this extraordinary practice, Wong began to amass a library of what little scholarly research had been carried out on the practice. He published his first paper in 1991 in a US archeology journal.

However, it wasn’t until 2000, once Wong had founded the non-profit China Exploration and Research Society (CERS), that he was able to get up close and excavate one of these high-rise cemeteries – at a site named Washi in northern Yunnan not far from the first site Wong laid eyes on.

He and his team rapelled down the cliff face to assess the coffins, which rested on rotting stakes of wood. They then built bamboo scaffolding to secure the most vulnerable coffins, which also allowed them to examine and document the contents.

What he found raised more questions than it answered. The oldest coffins dated back to the Tang dynasty but many contained bones from multiple bodies. Wong believes the bodies would have been buried first and the bones put in the hanging coffins once the bodies had decomposed.

The coffins, which were dug out of a solid piece of wood, were then packed with sand – making them enormously heavy. “They must have known they would eventually fall down,” says Wong.

Wong’s research has tied the burial custom to the Bo people – a rebellious minority tribe that once inhabited the border between today’s southern Sichuan and northwestern Yunnan provinces.

It’s thought they disappeared in the Ming Dynasty (1368-1644), persecuted by military expeditions led by China’s Imperial Armies. But Wong believes some remnants of the tribe assimilated into other local minority groups and may have survived secretly until today. His research formed the basis of a 2003 Discovery Channel documentary on the hanging coffins, where they attempted to recreate how the caskets would have been transported up the cliff face.

Some believe they were lowered down from above while others believe they were raised up via scaffolding.

It’s not just the mind-blowing effort it must have taken to erect the coffins that makes the cliff and cave burials so fascinating. The custom seems so at odds with underground burial and cremation – the way most modern societies, including China’s, handle death.

But the open-air burials do have something in common with other funerary practices in China’s borderlands. Tibetans and Mongolians practice sky burials – where bodies are chopped up and offered to vultures or other animals.

In more recent years, Wong’s obsession has taken him to Sagada, Luzon, in the Philippines, where cliff burials were practiced as recently as 2007.

No protection?

Earlier this year, I inadvertently rekindled Wang’s interest in China’s hanging coffins when I shared some photos of the caskets in a cave in Guizhou I came across unexpectedly during a trip to the province in 2016.

Never having heard of hanging coffins in this area, Wong set out from his China field office in Kunming in the neighboring province of Yunnan with a small team to find out more. The cave where the coffins are located is only accessible by river, which emerges from the spectacular limestone cave where the coffins are stacked.

“I like when information comes to me like this in a personal way,” says Wong. “The Internet, there’s so much information available. It takes away the joy and the reward for big effort. I like the footnotes.”

Li Fei, a researcher at the Guizhou Provincial Institute of Archaeology, says that there were up to 100 cave coffin sites in the province and the burial practice was followed by Yao and Miao minorities in the region. Most of the coffins date back to the Ming or Qing (1644-1912) dynasties, he adds, though some date back to the Tang dynasty.

The Guizhou site Wong and I visited, like others, wasn’t well-protected. Reluctant to scramble up the rocky sides of the caves I didn’t get close, but Wong said that while some of the 30 or so coffins were intact, most were falling apart – bones and disintegrating clothing visible.

Wong was told that there used to be more than 300 coffins in an elevated part of the cave but a fire destroyed them.

Banknotes have also been left by more recent visitors to the site, a superstitious offering for the dead, though not all visitors are respectful – one skull had a cigarette jutting out of its jaw. In a steep gorge down river, local tourist authorities have erected fake hanging coffins – perhaps an effort to satiate tourist curiosity and preserve the existing site.

Looting

In 1999, at one of the most famous hanging coffin sites in Matangba, Sichuan, which Wong had first visited in the 1980s, he discovered that many of the coffins had been looted – despite being some 90 meters above the ground and being protected as “national cultural relics.” The swag allegedly included ancient swords and other valuables, says Wong.

“Going back 20, 30 years, yes China had different priorities and limited funding, but today China has such influence and (protecting these sites) would be small change. It’s about the integrity of the their culture and cultural identity. “

Xu Jin, a researcher at Chongqing Cultural Heritage Research Institute, studies a hanging coffin site at Longhe, near Chongqing, where coffins are grouped by families. He’s held educational events to teach people about the coffins.

He says in a karst region where caves and cliffs are plentiful, burying the dead at a height might have seemed a better option than in land that erodes easily and is prone to sinkholes.

Little studied

Archeology in China is a well-funded and well-regarded field but the study of the suspended coffins appears to have been neglected.

Anke Hein, an archeologist at Oxford University, who has studied burial customs in western China, says the phenomenon straddles different time periods, geographical regions and even disciplines – falling between archeology and anthropology.

“I’m sure if someone really wanted to do this they could,” says Hein. “But you would need the cooperation of difference provinces and local governments, which is difficult, and requires a lot of energy.”

Most expertise seems to be regional, confined to provincial bureaus that focus on individual sites rather than the practice as a whole.

The earliest mention of them in Wong’s library is an account by a US missionary in the 1930s. The most comprehensive study in Chinese is by a scholar named Chen Mingfang, who was colorfully profiled by the Los Angeles Times in 2001. Now likely in her seventies, CNN was unable to track her down.

Wong’s spent much of his career exploring, documenting and trying to protect traditions like these in China’s borderlands but he doesn’t think the mystery of exactly how or why people chose to bury their dead in this way will ever be known.

“We can only speculate,” he says.

CNN’s Serenitie Wang contributed to this report