Two things on the rise in the Antarctic peninsula: temperatures and tourism.

An unprecedented 17.5 C (63.5 F) was recorded by the World Meteorological Organization (WMO) at the Argentine Experanza research base in March 2015 – pretty much T-shirt weather.

Meanwhile, as of July 2017, 63 vessels are registered with the International Association of Antarctica Tour Operators (IAATO), including some big names in cruising, such as Hurtigruten, Holland America Line, Seabourn, Silversea and Celebrity Cruises.

Between them they brought around 38,500 visitors on tourist expeditions to the white continent in the 2015–16 season – an increase of nearly 10,000 over the past decade.

But are these fuel-guzzling trips ultimately harmful to the region – or can they also be a force for good?

On board Lindblad Expeditions’ National Geographic Explorer in early February 2017, there are typical Antarctic tour scenes.

Passengers armed with binoculars and telephoto zoom lenses mill around deck in complimentary bright orange parkas adorned with a variety of patches attesting to their intrepid adventures.

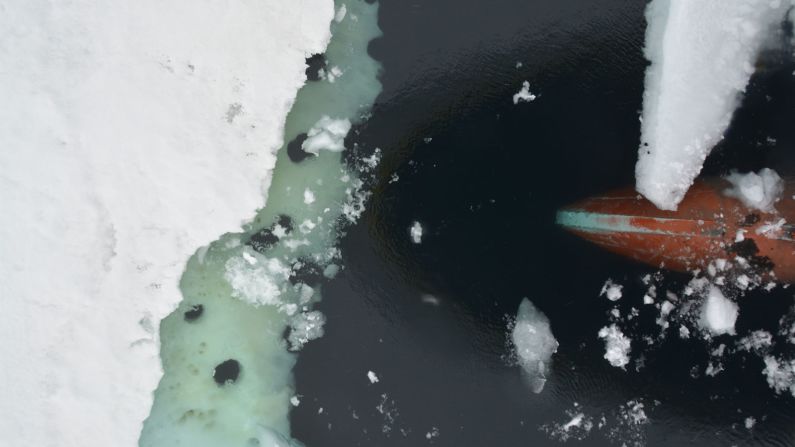

The ice-class ship smashes its reinforced hull through a vast expanse of pack ice, a crack riddling across the surface towards a king penguin that regards the vessel with a backward glance before waddling off.

For these voyagers, at least, the journey south is over. The sea is simply far too frozen to progress.

Rite of passage

“I’m kinda glad we’re not going to make it down past the Antarctic Circle,” says on-board naturalist and photo instructor, Eric Guth, who – as part of his role with Lindblad Expeditions – has been taking part in the Extreme Ice Survey project founded by James Balog, by setting up cameras in Antarctica to monitor glacial recession.

For many polar vacationers, it’s a rite of passage to cross that invisible boundary.

“It’s just that though,” he argues. “It doesn’t look any different; there’s no neon flashing signs. It’s just a pointless exercise for the sake of saying you’ve done something abstract, while burning tons of fossil fuel in the process.”

He has a point. Contributing to climate change really isn’t in the spirit of visiting this pristine wilderness.

It makes you wonder whether we should be visiting at all, leaving our dirty great carbon footprints in the snow.

“Increasing tourism in Antarctica is something we need to be mindful of, with all these ships burning fossil fuels,” says John Durban, a British killer whale researcher from the US National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, who is conducting whale and orca population research in Antarctica as a guest of Lindblad.

“But there are a number of threats down here, ranging from the small-scale disturbance from tour ships to large-scale climate change.”

Regulated tourism

However, Durban insists that the benefits of taking the public to these environments shouldn’t be underestimated; polar tours raise climate change awareness and create wildlife ambassadors, while tourist dollars fund scientific expeditions such as his own.

“Tourism isn’t progressing in an unregulated fashion,” says Durban. “The IAATO scheme agrees on best practices to minimize the impact on the environment.”

IAATO-registered tours are limited to no more than 500 passengers on their ships, with only 100 allowed ashore at any one time.

They take their responsibilities seriously too.

Before stepping ashore on the Antarctic peninsula, the Lindblad tour group is subjected to rigorous decontamination procedures, which involves vacuuming every crevice, crack and cranny of clothing, sucking up seeds, pollen and – inevitably – rather a lot of pocket lint.

They don’t want any invasive species sneaking into Antarctica as Velcro stowaways.

Durban isn’t the only researcher on board.

During the voyage, Kendrick Taylor, the chief scientist on a National Science Foundation project investigating the role of greenhouse gases in climate change and the stability of the Antarctic ice sheet, presents travelers with shocking data he’s collected by analyzing ice-core samples.

Containing bubbles of ancient air, and preserving layers of antediluvian dust, the ice acts as an ageless record of atmospheric gases, and, says Taylor, clearly shows that CO2 levels are now at their highest in at least the past 800,000 years.

These ice cores provide data that enables scientists to predict both the possible and inevitable effects of climate change.

Dubbing the coming era the Anthropocene – an epoch where human activity rather than nature is the major influence on the Earth’s physical and ecological systems – Taylor promises an 8 F temperature increase by 2100, if mankind doesn’t mend its ways.

He adds that we can expect much more dramatic effects for human life than the mere numbers suggest – like the inundation of Manhattan, for example.

Effects on marine life

But with a reported 5 F rise in temperature on the Antarctic Peninsula over the past 50 years, there are some signs that, perhaps, Antarctica’s marine life is already being affected.

Type B1 killer whales feed almost exclusively on Weddell seals, which they hunt by washing them off floating chunks of pack ice.

On the Lindblad’s February visit, much less ice than usual for that time of year was observed alongside some very skinny killer whales. Weddell seals were only spotted lazing around on land – unwittingly staying where orcas can’t get to them.

A NASA report from March 2017 found less sea ice surrounding the Antarctic continent than at any stage since reliable records began back in 1979.

Adélie and chinstrap penguins, whose diets rely heavily on the krill which feed off the algae growing under the sea ice, have seen their numbers decline. Less ice means less algae which means less krill.

Gentoo penguins, however, have been flourishing.

They have a more versatile diet than their feathered neighbors, thanks to their ability to dive further – thereby reaching more kinds of food – and their habit of foraging closer to shore.

It’s a matter of adaptation.

At Palmer Station, a US research base, what has to the world’s most southerly gift shop sells T-shirts, hoodies and bumper stickers. It’s clearly set up for tourist arrivals.

And while tens of thousands more parka-clad visitors will join the tuxedo-wearing penguins on the ice in the 2017-18 season, the profits from responsibly managed tourism help to fund scientific expeditions to the Antarctic.

Habits need to change in order to ensure survival – and for humans the key to that is education. When the expedition ship returns to shore, it will do so with a boatload of green energy advocates on board.

READ: Adventure travel – 7 great trips for 2017

READ: 9 places on Earth we know very little about

James Draven is an award-winning freelance travel journalist, editor, blogger and photographer. His writing and pictures appear in National Geographic Traveller, The Sunday Times Travel, The Guardian, The Telegraph, The Independent and more.