The architecture of OMA

Editor’s Note: This series is, or was, sponsored by the country it highlights. CNN retains full editorial control over subject matter, reporting and frequency of the articles and videos within the sponsorship, in compliance with our policy.

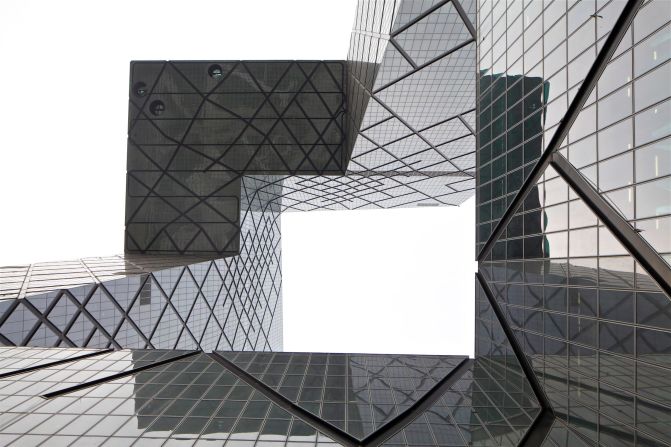

Rem Koolhaas is always looking for an exit. The Pritzker Prize-winning architect behind the CCTV Headquarters in Beijing, and De Rotterdam in his homeland of the Netherlands, is prone to claustrophobia, and won’t risk triggering it with one of his own buildings. This fear has reshaped skylines, pushing upwards and outwards, leaving behind open, unfussy spaces inside Koolhaas’ modern exteriors. “In all my buildings, you could say I’m trying to escape,” he told CNN.

Libraries and Koolhaas are not an obvious fit. The popular image of them — labyrinthine, stuffy, dimly lit — hardly aligns with his aesthetic sensibilities (“the typical illumination of libraries is deeply unpleasant,” he remarked). Yet his Seattle Public Library, completed in 2004, is one of his most famous works, and when he designed the Qatar National Library he tore up the rule book once again. Open, airy, you’d never know there were over a million books under its sloping roof, despite so many being so clearly displayed.

The building in Doha opened in 2018, and it’s here that CNN recently spoke with the renowned founding partner of international architects OMA.

Qatar, on the Arabian peninsula, is home to around three million people, the majority expats. Koolhaas has had multiple projects here, and says of all the places he’s worked, he has “maybe the longest-lasting relationship” with the country.

It could’ve started earlier. In the late 1990s, Japanese architect Arata Isozaki was working for a local person of importance and called Koolhaas. “He asked me, do you want to design a bungalow for a horse?” the Dutchman recalled. “I was so puritanical that (I said), ‘A bungalow for a horse? Never.’ Now that I’ve been here much more, I realize that it could have been a fantastic opportunity.”

Starchitect? “I hate it”

Unsurprisingly for a man who wrote “kill the skyscraper” in 2004, Koolhaas does not believe tall is the be all and end all of place-making. “I still think that skyscrapers are not necessarily the most interesting topology that you can think of,” he said. There are other ways to cement a destination: airports, museums, and, yes, libraries. OMA, which is led by eight partners, has played a part in the stories of nations moving into the global spotlight, and not just Qatar. China, Colombia, Saudi Arabia — the company has produced significant work in them all. But despite having a hand in these narratives, Koolhaas is happy to let go of projects once they’re done.

“Once (a building) exists independent of myself, I don’t consider that it was mine. I can almost forget that I was the one who played an important role in generating it,” he explained.

In his uniform black turtleneck and trousers (he has a longstanding relationship with Prada), he bristles at the mention of “starchitect,” a moniker which has dogged him for decades. “I hate it. I hate it because it’s a total caricature, and basically says you are an awful person who walks over people, who has no interest in clients, and who is a nightmare to deal with,” he bemoaned.

“It’s a form of laziness of the critical apparatus, because I think there’s so much more to say,” Koolhaas added. “The word ‘star architect’ is so superficial in terms of the total engagement that building something requires … ‘Okay, he’s parachuted in and then he does a little trick and disappears.’ Every single building is so much work. I’m not saying that as a victim, but it’s so much work.”

Koolhaas has thought extensively in recent years about use of space and resources. “Countryside: The Future,” a Koolhaas-led exhibition at the Guggenheim Museum in New York in 2020, posited the countryside had experienced radical change to make urbanization possible. That it had become a dumping ground for the structures a city needed to survive but could not handle — data storage and fulfilment centers and the like. As an architect commissioned to work at masterplan scale, it amounted to a period of reflection.

The city itself is in need of a rethink, he argued. “Ultimately if we are to take sustainability seriously, climate seriously, I think we will maybe enter a period where skylines of cities become less heterogenous,” Koolhaas said. That means fewer extremely tall buildings rubbing shoulders with extreme horizontals. “I can also imagine that there will be a more equal distribution through city and country. I predict — but it’s a very dangerous prediction — that there will be new ways of inhabiting the countryside, but in a more responsible way.”

Koolhaas has long been a philosopher king of architecture, both a standard bearer and a critical, contrarian presence. A former journalist, he still writes extensively, a “double life” he said, where he “can do and write what I want,” independent of his office.

“It’s been equally exciting to also remain a writer,” he expanded, “and to think about issues that have nothing to do with myself, but that are simply comments on the situation in the world or perceptions; how cultures are changing, or insights in human relations.”

The industry has little room for ideologues however, demanding pragmatism and occasional deference to market forces.

Koolhaas says in the past, architects largely served a civic function, working for public bodies. The siren song of the private sector emerged around the time he entered the profession, during Ronald Reagan’s and Margaret Thatcher’s political ascendance in the late 1970s and 80s.

“The period of neoliberalism that they unleashed of course had a huge impact on architecture,” he said. “In a very subtle way, (it) eroded the plausibility of an architect, because we could no longer say ‘we are doing this for the public,’ or ‘we are doing this for your wellbeing.’ We typically started working for individuals that had their individual ambitions.”

Despite Qatar’s centralized power structure, led by an emir who signed off its National Vision 2030 project, Koolhaas names the country as a point of contrast, arguing there is a civic element to the work there. “Of course, they’re private plans, but the state of Qatar is very strong, and has these very defined ambitions, that as an architect you can work within and for,” he argued. “This is the one place where ambition has constantly outworn my skepticism,” he added.

The relationship rolls on, with OMA designing the upcoming Qatar Auto Museum. The 30,000 square meter museum, on the site of the 2011 Qatar Motor Show, does not yet have a completion date, but is a fitting symbol for a petrostate pivoting toward a knowledge economy. Expect the usual hallmarks: the clean lines, the playful irreverence, the nods to local shapes and forms.

Koolhaas might always be looking for an exit, but not from here.