Favored by hardened yakuza gang members and law-abiding body art purists alike, large-scale Japanese tattoos are widely celebrated for their distinctive style, mythological motifs and vibrant coloring.

But while many of the common motifs are steeped in history and folklore, Japan’s pictorial tattooing tradition is relatively new. Before the Edo period (c.1615-1868), tattoos were primarily used as crude markers of punishment for petty criminals or of fealty for lovers, or else the domain of the indigenous Ainu tribes of the northern islands.

According to “Tattoos in Japanese Prints,” a new publication from the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, it was only in the 19th century that they were elevated to the level of art.

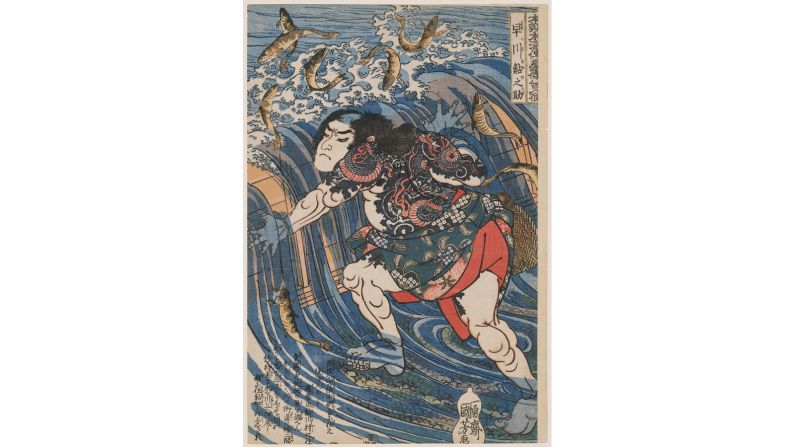

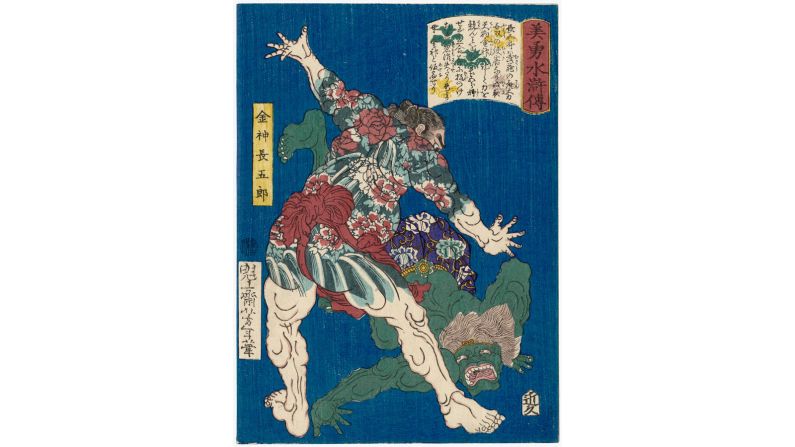

Author Sarah E. Thompson, curator of Japanese art at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, traces their popularity back to the publication of “One Hundred and Eight Heroes of the Popular Water Margin,” a series of woodblock prints by the artist Utagawa Kuniyoshi, between 1827 and 1830.

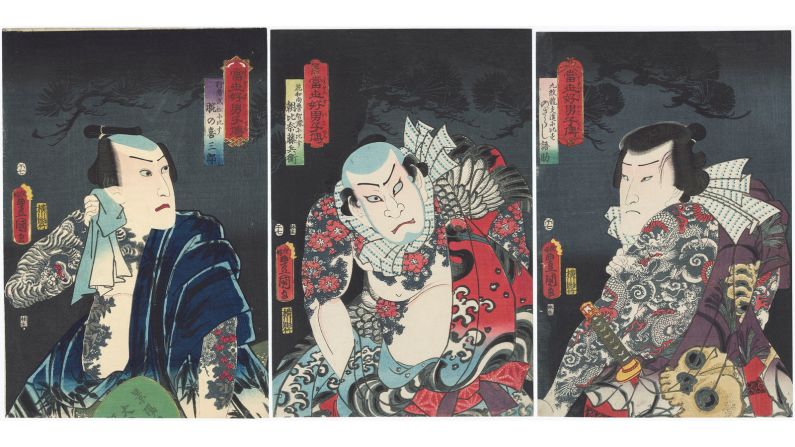

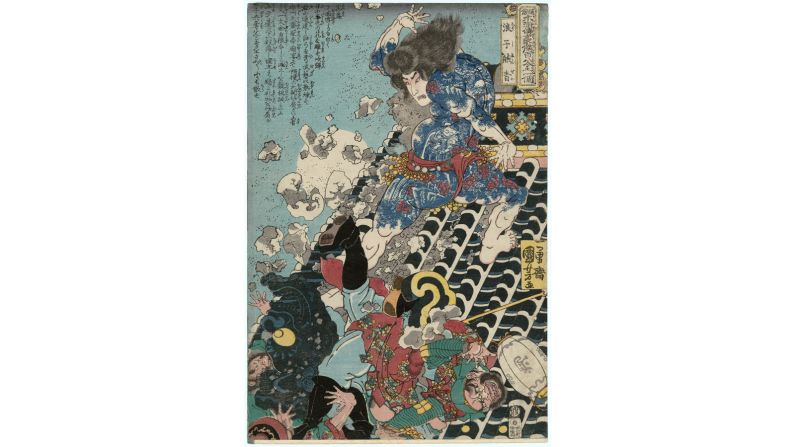

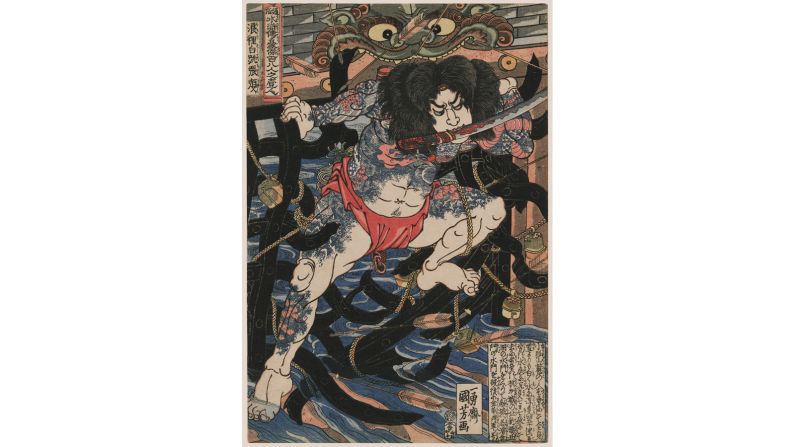

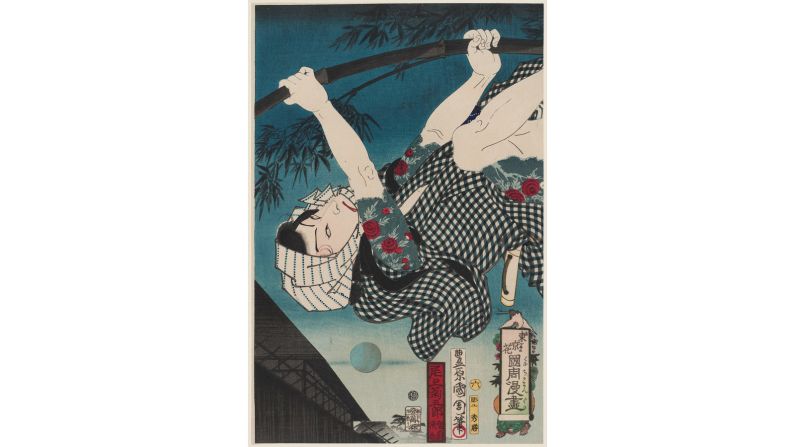

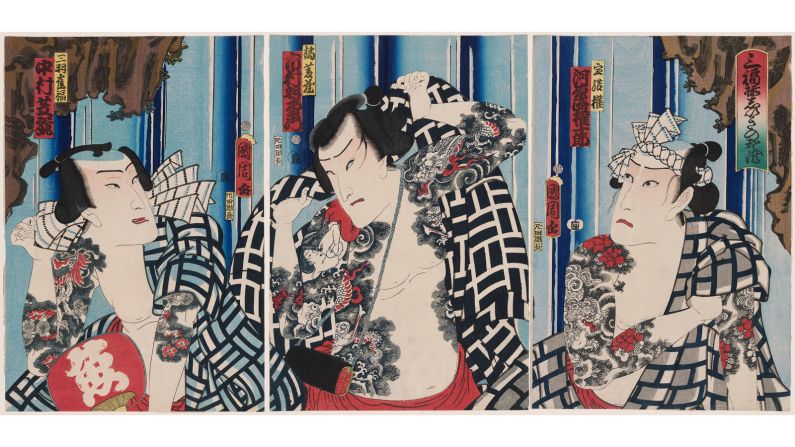

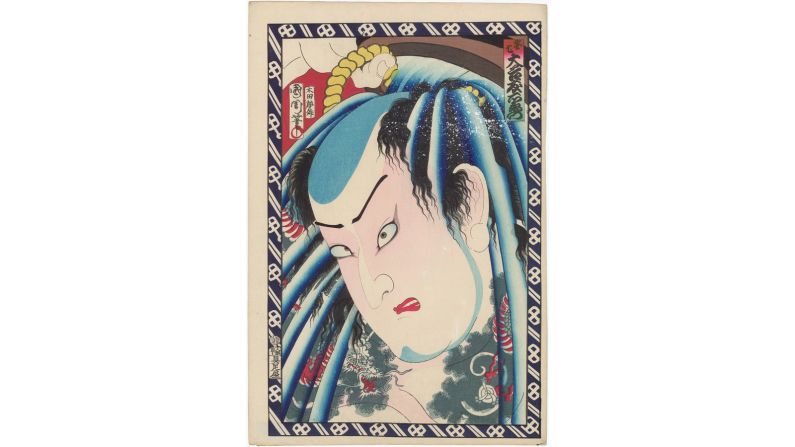

His prints, adapted from a 14th-century Chinese novel, saw bandit heroes covered with elaborate, full-body tattoos rendered in impressive detail. The common motifs – dragons and demons, fearsome predators, koi fish and cherry blossoms – were laden with meaning, and added another layer to the narrative.

Deciphering the tattoos in Japanese prints

“By emphasizing the tattoos sported by some of the heroes, Kuniyoshi’s print designs not only exploited the allure of the exotic but also provided a titillating hint of the illicit – especially if the suggestion that pictorial tattoos in Japan had been outlaws and spread to fashionable urbanites is correct,” Thompson writes.

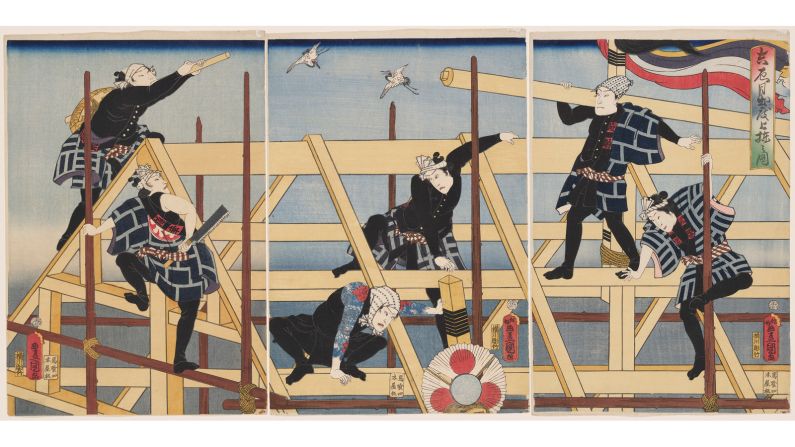

The impact of the “Water Margin” series and similar works from Kuniyoshi and his contemporaries was immediate and broad-reaching. Men across class lines requested tattoos of scenes from “Water Margins” – and, in some cases, the characters’ tattoos. Textile artists started incorporating tattoo-like prints into their designs; kabuki stars painted simple designs onto their skin for performances.

(The tattoos did have their detractors, however. In 1872, as Japan started its push toward Westernization, tattoos were banned by the Japanese government, who considered them uncivilized and old-fashioned. This ban was lifted after the American occupation after WWII.)

“It is uncertain whether Kuniyoshi was responding to a recent craze for extensive pictorial tattoos, or whether – as suggested by oral tradition among present-day tattoo artists – it was the prints themselves that inspired the new fashion,” Thompson writes.

“Perhaps the answer lies somewhere in between: large tattoos were already beginning to appear, but it was Kuniyoshi who transformed a temporary fad into a lasting art form.”

“Tattoos in Japanese Prints” by Sarah E. Thompson, published by the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, is out now.