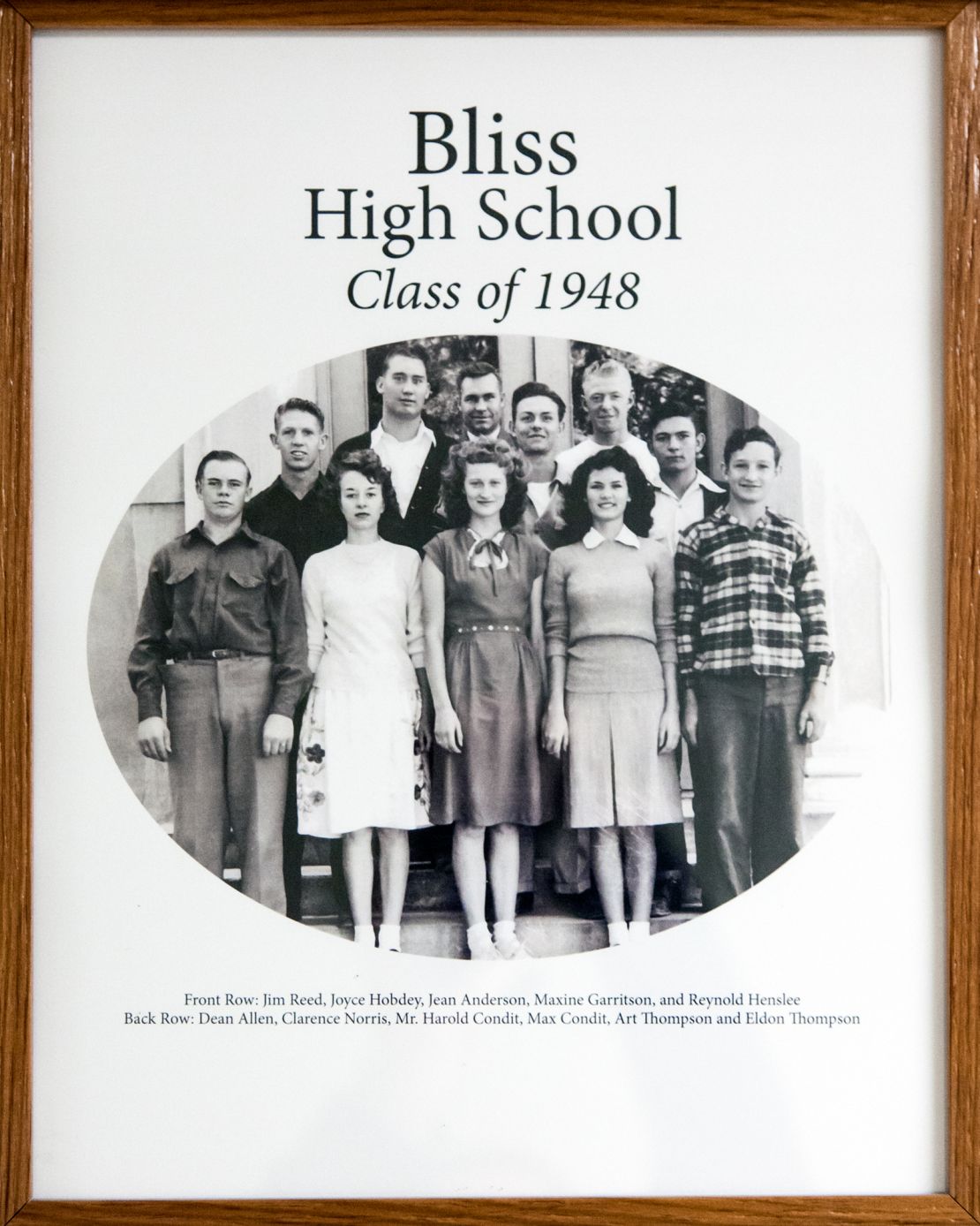

Bliss, Idaho, is nestled in the curve of Interstate 84, which snakes around the small, rural town on its way north to the state capital, Boise, some 85 miles away. When Milwaukee-based photographer Jon Horvath first visited Bliss in the late summer of 2013, he was on a meandering road trip following the end of a relationship. At the time, around 300 people resided there, served by a small community church, K-12 public school, diner, post office, gas stations, motels and two bars.

“If you find yourself there… it’s likely to be simply to fill up your gas tank, maybe catch a quick meal at the diner, but that’s probably about it,” Horvath explained in a phone call.

Buck Hall, a Bliss resident, told Horvath on his first visit that the town had once seen more regular visitors, but that construction of the Interstate decades ago had shifted traffic away, the photographer recalled. Once a place to pass through, Bliss became a place to pass by — a touch of irony on an exit sign.

“(Hall) summed up the state of the town,” Horvath recalled of this early conversation. “His words were: ‘We’re a town of 300 people, and 299 when I die.” (Since Horvath’s photographs of Bliss, a new truck stop has brought additional jobs to the town, but the 2020 census reveals that its population is now just above 250. Buck Hall passed away in 2021, at the age of 75.)

Horvath’s first images of Bliss just scratched at its surface — he took the expected images of deteriorating or empty spaces that contrasted with the town’s name, he explained — but as he returned over the course of three years, drawn to the people he met there and their stories, a more complex body of work began to take shape.

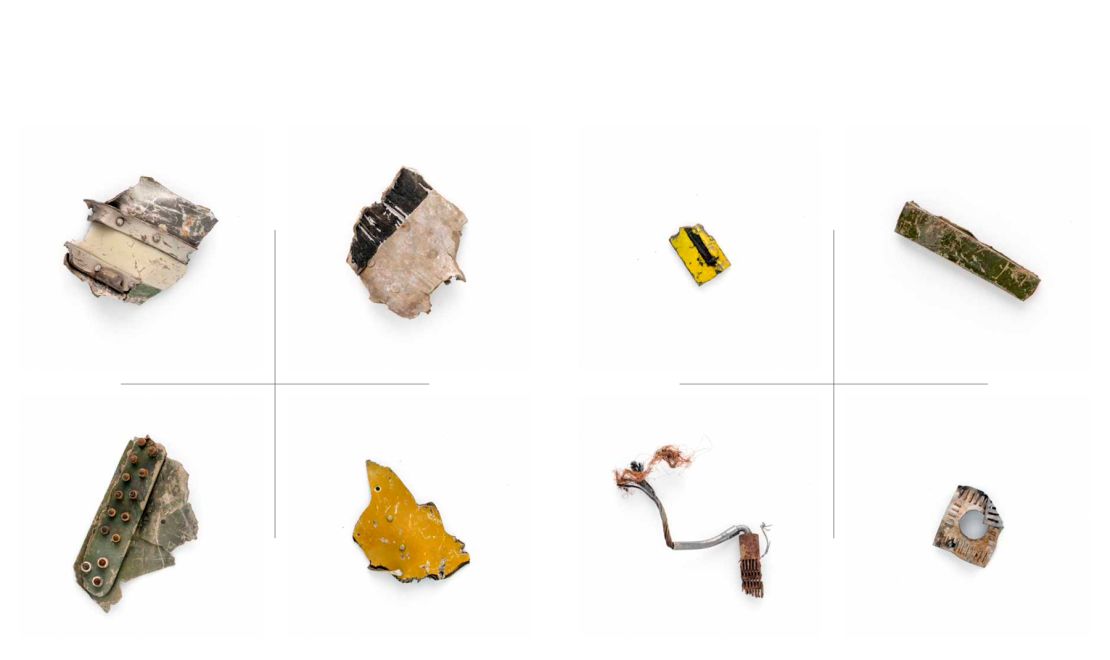

Now a book titled “This is Bliss,” Horvath’s body of work doesn’t follow a traditional documentary-style record of a place. Instead, black-and-white and color film photographs, tintypes, archival images, ephemera and scanned objects from Bliss form a sort of dreamlike time capsule.

During his time there, Horvath found a different way of telling a story about the American West. Rather than the sprawling photographic explorations of the region lensed by photographers like Robert Adams or Stephen Shore, “This is Bliss” mostly covers a small area — roughly a mile-wide — that Horvath continually returned to, peeling back the town’s layers.

“There is a macro level to the work that was looking at a longer, deeper history of the region,” Horvath said, “and some of the stories that we tell about ourselves as Americans.”

Bliss may be a small mark on the map, but it’s been part of much bigger stories: It’s located on the Oregon Trail, a throughway for settlers to expand West during the rush of Manifest Destiny. It’s close to where stunt motorcyclist Evel Knievel famously attempted (and failed) to jump Snake River Canyon in 1974, Horvath pointed out. And it was home later in life to author JD Salinger’s friend Holden Bowler, for whom Salinger’s famed “Catcher in the Rye” protagonist Holden Caulfield was named.

“There’s all these myth-making events within our own history that (have) come to have some presence in this town,” Horvath said,

But there’s what Horvath calls a “micro line” in the narrative too, from the residents’ lives to his own “quest to rediscover what ‘bliss’ might be.” He added: “A mythology exists there too… my arrival to town coincided with a restart in my own life.”

Some of his experiences in Bliss feel like fiction, Horvath said — like the time he was served by a bartender named Cinderella. Hall once instructed him to drive to a cliffside by moonlight and he’d find a rock formation that local legend has enshrined as the craggy profile of a Native American chief; Horvath did so and snapped a picture, which has become a self-printed postcard enclosed with the book.

During one visit, he drove to a nearby gravesite with only six plots, marked by crooked white wooden crosses and a faded sign etched with “Chinese Memorial Cemetery.” A historical pamphlet Horvath purchased in a local gas station claims that the plots hold the bodies of 16 migrant railroad workers who died in an explosion in 1883 and were buried together, though that total is disputed.

All of our stories and memories shape a place, as imperfect as they may be. Horvath isn’t a historian, and so as he gathered anecdotes and records of Bliss, he said he accepted them all, fact-checked or not, as part of the town’s archive. “I loved the idea that I’d meet Buck Hall on the side of the road, and he’s (telling) me stories,” he added. “Are they true? Are they not true? Maybe in a different universe that would matter.”

Fittingly, at the end of “This is Bliss,” Horvath wrote a piece of short fiction loosely based on his experiences there.

“We either embellish or we take liberties, or we bring some of our invention to them,” he said.

“This Is Bliss,” published by Yoffy Press and FW:Books, is available now.

Top image: Buck Hall reflected in the hood of Horvath’s car.