When he was 17 James Barnor took his first picture, using a small camera a craft teacher gifted him. His subject was a “clever and lovely” girl who he knew from school.

“Growing up in Ghana, I was surrounded by people who wanted to have their picture taken,” Barnor said during a phone interview. “I don’t regret not taking pictures of landscapes. I started out as an apprentice portraiture photographer; people came to be photographed or (I would) go to weddings and school groups.”

During his career spanning six decades, the Accra-born photographer has remained unwavering in his mission statement: People are more interesting than places. Now, having just turned 91, Barnor is one of Ghana’s most well-known photographers, though it’s only in this century that his work has been celebrated in exhibitions across Europe and in the US – after curator Nana Oforiatta-Ayim organized his first solo exhibition in 2007, held at the Black Cultural Archives in London.

Since then, Barnor’s photos have been acquired for The Victoria and Albert Museum and Tate’s permanent collections, and last year the Nubuke Foundation in Accra held a retrospective of his work (the first time the foundation has hosted a retrospective of a homegrown photographer). And the Serpentine Galleries in London were scheduled to host a retrospective to coincide with Barnor’s birthday this month (due to Covid-19 restrictions, this is now postponed until 2021).

It was as the first photojournalist appointed to the Daily Graphic, a Ghanaian state-owned daily newspaper in Accra, that Barnor honed his craft and developed a documentary eye. He took pictures of the city’s people and events – everything car accidents and football matches to locals at the market.

“I’d just take my camera and my bicycle and go to the market,” he said. “I’d spend about 20 minutes there and I’d come back to my darkroom, with pictures all telling different stories. I did that a lot. You capture the market woman the way she actually is. It takes some art, some patience, and technique to photograph people in that setting.”

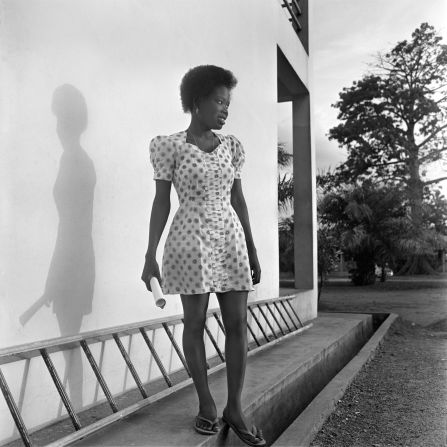

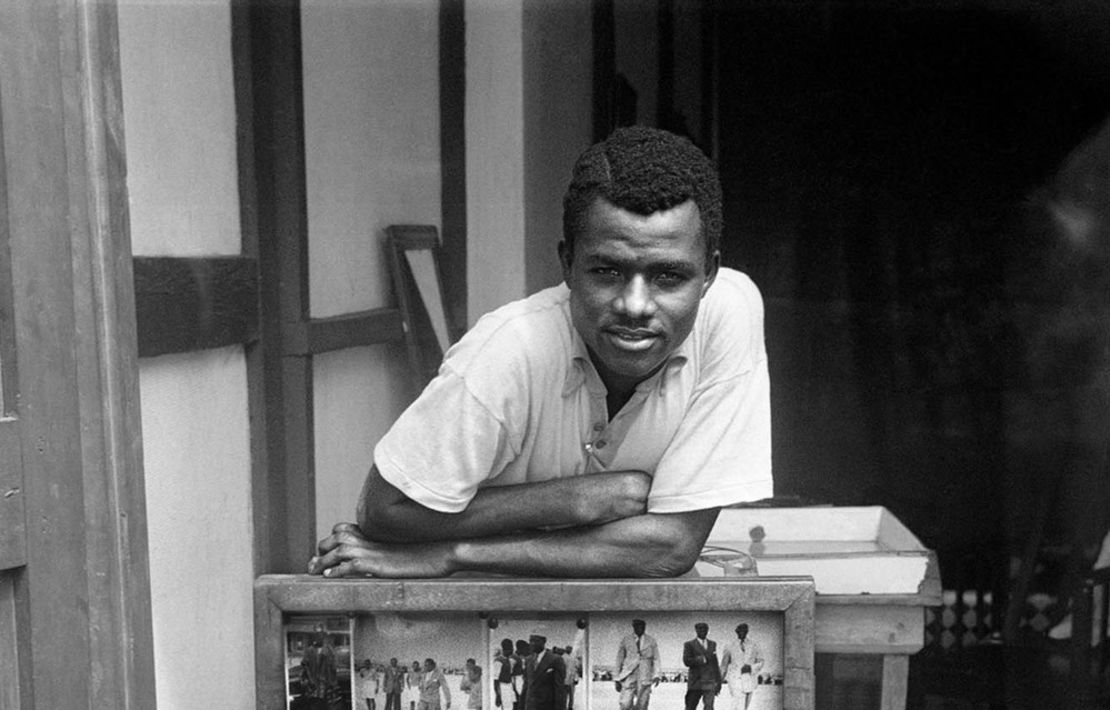

Alongside his photojournalism, Barnor took portraits of local residents at his own makeshift studio, which he christened Ever Young, in the Jamestown district of Accra, mostly between 1949 and 1959. While this was predominately a commercial proposition, taking on paid portraiture commissions and passport headshots, he developed a natural exchange with many of his subjects.

Barnor’s studio was like a “community center,” he remembers, and he made “people feel at home,” by talking to and getting to know them. “Young men would come by to have a chat and have their photograph taken,” he said. “Most people had confidence in me already. Everybody knew me in Ghana as a successful photographer – they knew they would be satisfied.”

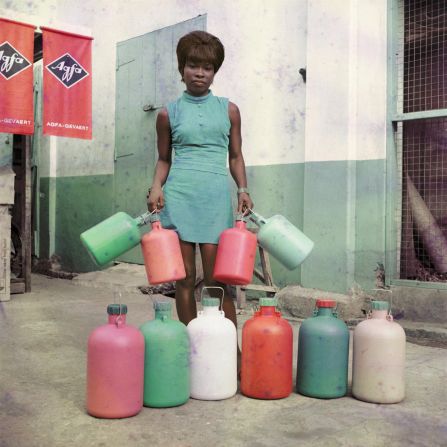

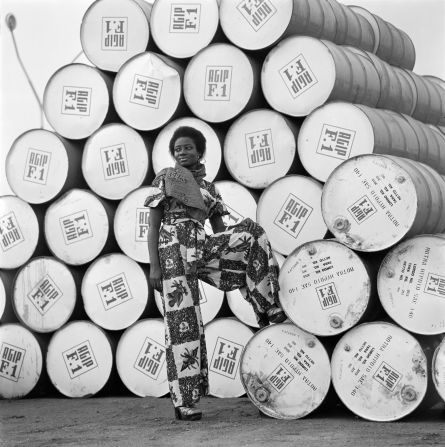

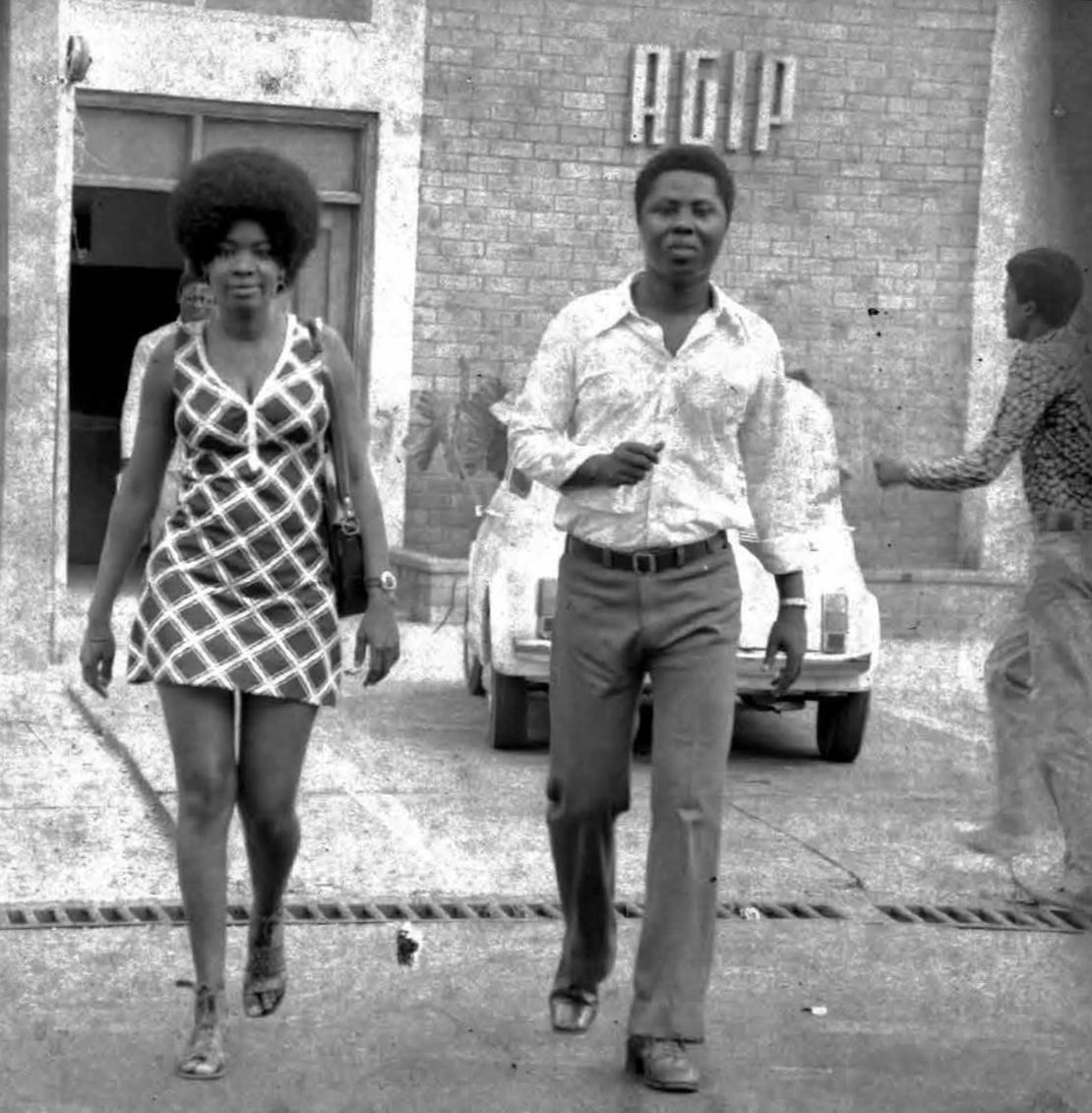

Barnor says he believes the photographs he took during this time showed a different, stylish view of his home country – one that belied assumptions. “When I had my studio in Ghana people thought we (Ghanaians) didn’t dress up,” he said. “But all my sitters, my friends, were fashion conscious – women would often request full-length photos with shoes, a handbag and their accessories.”

In 1959 Barnor moved to the UK after receiving a scholarship to study at the Medway College of Art in Rochester, Kent. After graduation in 1961, he moved to South London, reveling in the capital city’s “colors, adverts, uniforms and music.”

From Acrra to London, how photographer James Barnor captured decades of style

But it wasn’t all smooth sailing. “If you wanted a room or something and you were Black (people would say) ‘Oh – it’s gone,’” Barnor said. “This is what it was like. I was lucky though – I call myself Lucky Jim. Before I left Ghana, I befriended somebody who worked at the Colonial Office (a government department that oversaw the administration of Britain’s territories). He helped me find somewhere to live, introducing me to a Jamaican man in Peckham.”

Once in London, Barnor mostly produced work for anti-Apartheid journal Drum magazine, for whom he had already worked making fashion stories while he was still living in Ghana. At the time, Barnor recalls, the magazine stood out for featuring Black models in its pages and on its covers.

“There weren’t magazines or newspapers showing Black models – Drum started it,” he said. “Any time I saw a Drum cover in London, side by side with international magazines, I felt really satisfied. I knew I was recording something. I knew I had to take care of my negatives.”

As part of his work with Drum, Barnor captured the BBC’s first Black broadcaster, Mike Eghan, on the steps of the famous Eros statue in Piccadilly Circus, central London. Another photo shows street-scouted cover girl, 19-year-old Erlin Ibreck – whom he met waiting for a bus – feeding pigeons in Trafalgar Square.

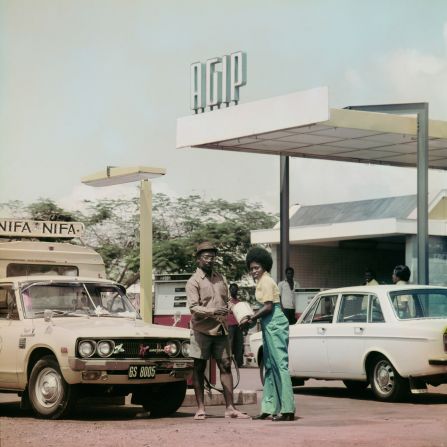

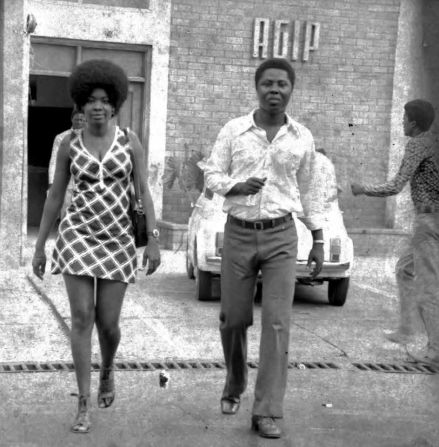

Like his time capturing individual style in his studio portraiture in Accra, in the UK Barnor amassed a large archive of street photos, chronicling how Black people were dressing in bright western fashions distinctive of the era. But unlike his monochrome photos from earlier days, he was now working in color, a transition that has helped define his signature style. “My learning, and everything, is around how the Black body appears in color,” he said. “With all these lovely color dresses.”

As well as paid fashion editorial work during the 1960s, Barnor took photos of his friends and sought out subjects from the Ghanaian and wider African communities in South London. The resulting archive – spanning about ten years form 1959-1969 – is a goldmine of street style reportage, editorial shoots and portraiture of the African diaspora in the UK.

And though standalone landscapes were not of interest to Barnor, he liked to choose locations and backgrounds that spoke to time and place.

“I like vantage points or places which connect to where you are,” Barnor said. “A secluded background, unless it’s helping in some way artistically, is not so good. I have a picture of two friends, I posed them in front of a telephone kiosk. When you see the image, you know: This is London.”

Barnor eventually returned to Ghana, in 1969, and spent over two decades there before returning to London, where he now resides. During that time he opened the country’s first color processing laboratory, with the hopes of sharing his knowledge and experience. “You want to bring people up, you want to advise them in whatever way you can,”

But skills, he says, are not the only thing that’s important, and to aspiring photographers, Barnor’s advice is simple: Tell a story that means something to you. “You can google all the technical stuff. It’s the ideas that you have that’re important. The community development, the self-involvement. Go and learn and be knowledgeable and take the camera. The story is the picture.”