Although we’re surrounded by millions of them every day, most of us don’t think about bricks too often. For thousands of years, the humble clay-fired brick hasn’t changed. The building blocks of modern suburban homes would be familiar to the city planners of ancient Babylon, the bricklayers of the Great Wall of China, or the builders of Moscow’s Saint Basil’s Cathedral.

But the brick as we know it causes significant environmental problems, by using up raw, finite materials and creating carbon emissions. That’s why Gabriela Medero, a professor of Geotechnical and Geoenvironmental Engineering at Scotland’s Heriot-Watt University, decided to reinvent it.

Originally from Brazil, Medero says she was drawn to civil engineering because it gave her passion for maths and physics a practical outlet. As she became aware of the construction industry’s sustainability issues, she started looking for solutions. With her university’s support, Medero joined forces with fellow engineer Sam Chapman and set up Kenoteq in 2009.

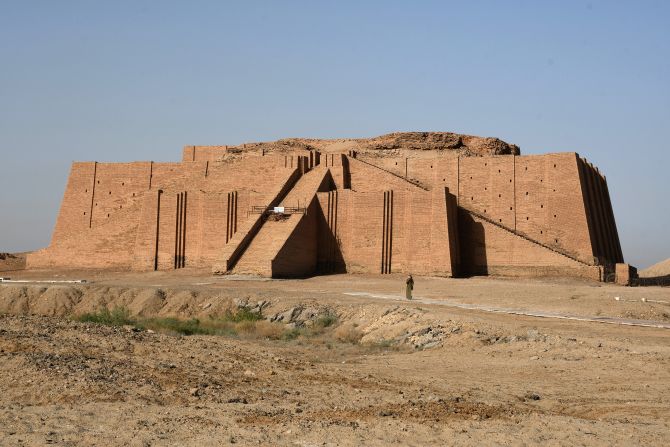

These buildings span 4,000 years, but they're all built with the same material

The company’s signature product is the K-Briq. Made from more than 90% construction waste, Medero says the K-Briq – which does not need to be fired in a kiln – produces less than a tenth of the carbon emissions of conventional bricks. With the company testing new machinery to start scaling up production, Medero hopes her bricks will help to build a more sustainable world.

The problem with bricks

Although they’re made from natural materials, there are problems with bricks at every step of their production.

Bricks are made from clay – a type of soil found all over the world. Clay mining strips the land’s fertile topsoil, inhibiting plant growth.

In conventional brick production, the clay is shaped and baked in kilns at temperatures up to 1,250°C (2,280°F). The majority of brick kilns are heated by fossil fuels, which contribute to climate change.

Once made, bricks must be transported to construction sites, generating more carbon emissions.

Globally, 1,500 billion bricks are produced, every year. Laid end-to-end, they would stretch to the moon and back 390 times.

The environmental footprint of different bricks reflects multiple factors including the type of kiln, fuel, and transportation. But with so many produced, their impact adds up, says Medero.

Enter the K-Briq. To make it, construction and demolition waste including bricks, gravel, sand and plasterboard is crushed and mixed with water and a binder. The bricks are then pressed in customized molds. Tinted with recycled pigments, they can be made in any color.

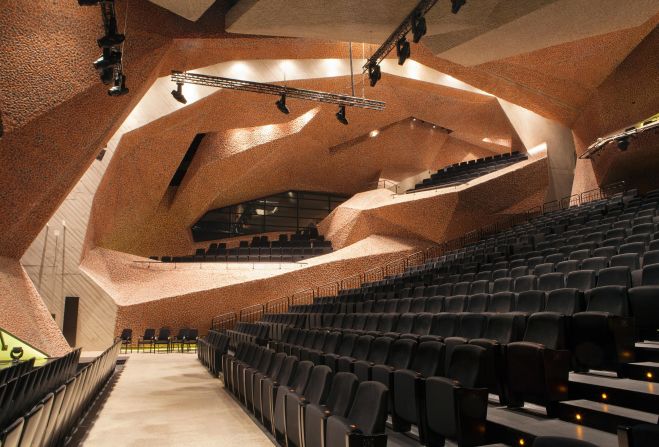

Earlier this year, Kenoteq won its first commission – to supply bricks for the Serpentine Pavilion 2020 in London’s Hyde Park (although the project has been postponed until summer 2021 due to the current pandemic). Designed by architectural studio Counterspace, the building will incorporate K-Briqs in grey, black and 12 shades of pink. The Pavilion’s lead architect, Sumayya Vally, says that as a recycled product, the K-Briq appealed to her. It “embodies” the past through its use of old materials, she says, adding that because the bricks can be customized, they allow “the designer to be a part of the construction process of the material,” creating unique opportunities in architecture.

Why can’t old bricks be re-used?

In the UK, around 2.5 billion new bricks are used in construction every year – and about the same number of old bricks are demolished. A seemingly simple solution to the brick production problem would be to re-use old bricks.

But it’s not that straightforward. According to Bob Geldermans, a climate design and sustainability researcher at Delft University of Technology in the Netherlands, reclaiming bricks is an expensive and “labor-intensive process.”

According to the UK’s Brick Development Association, old brick structures need to be carefully dismantled and the bricks cleaned of mortar with hammers and chisels. Reclaimed bricks are used to help renovate historic buildings or for other specialized projects but for mass construction, the process is too costly.

An additional barrier is that there’s no standardized way to check the strength, safety or durability of reclaimed bricks.

Medero says that K-Briqs could solve both these problems.

According to Medero, the K-Briq will be comparably priced to conventional bricks. Additionally, as a new product, the K-Briq has been subjected to rigorous assessment at the materials testing lab at Heriot-Watt University, and is in the process of being certified by regulators. Medero claims that K-Briqs are stronger and more durable than fired clay bricks, and provide better insulation, too.

Scaling up

Kenoteq currently operates one workshop in Edinburgh, which can produce three million K-Briqs a year. Medero is looking at scaling up – but it’s hard to create a revolution in construction.

Geldermans says that the industry is notoriously slow to change – adding that legislation often lags far behind innovation, so construction companies are not incentivized to adopt sustainable practices and materials.

Stephen Boyle is the program manager for construction at non-profit Zero Waste Scotland which, along with organizations including Scottish Enterprise and the Royal Academy of Engineering, has provided Kenoteq with funding. He attributes the industry’s conservatism to a “chicken and egg” situation. Innovative startups need large contracts to allow them to scale, he says, but struggle to become competitive without a large operation already in place.

But despite the challenges, Kenoteq is far from being the only company trying to make construction more sustainable. Other innovators include Qube, an India-based startup creating bricks out of plastic waste, and the ClickBrick which eliminates the use of cement through modular stacking (think real-life Lego).

There are signs of change. In Scotland, the government is reviewing a circular economy bill which encourages businesses to think creatively and economically about how they reuse and recycle materials. Boyle says that there are “contractors who would use [K-Briqs] tomorrow,” if they were being produced on a large scale.

Over the next 18 months, Medero plans to get K-Briq machinery on-site at recycling plants. This will increase production while reducing transport-related emissions, she says, because trucks can collect K-Briqs when they drop off construction waste. “We need to have ways of building sustainably, with affordable, good quality materials that will last.”

An earlier version of this story incorrectly stated that the K-Briq has British Board of Agreement certification. K-Briq is currently being certified by regulators.