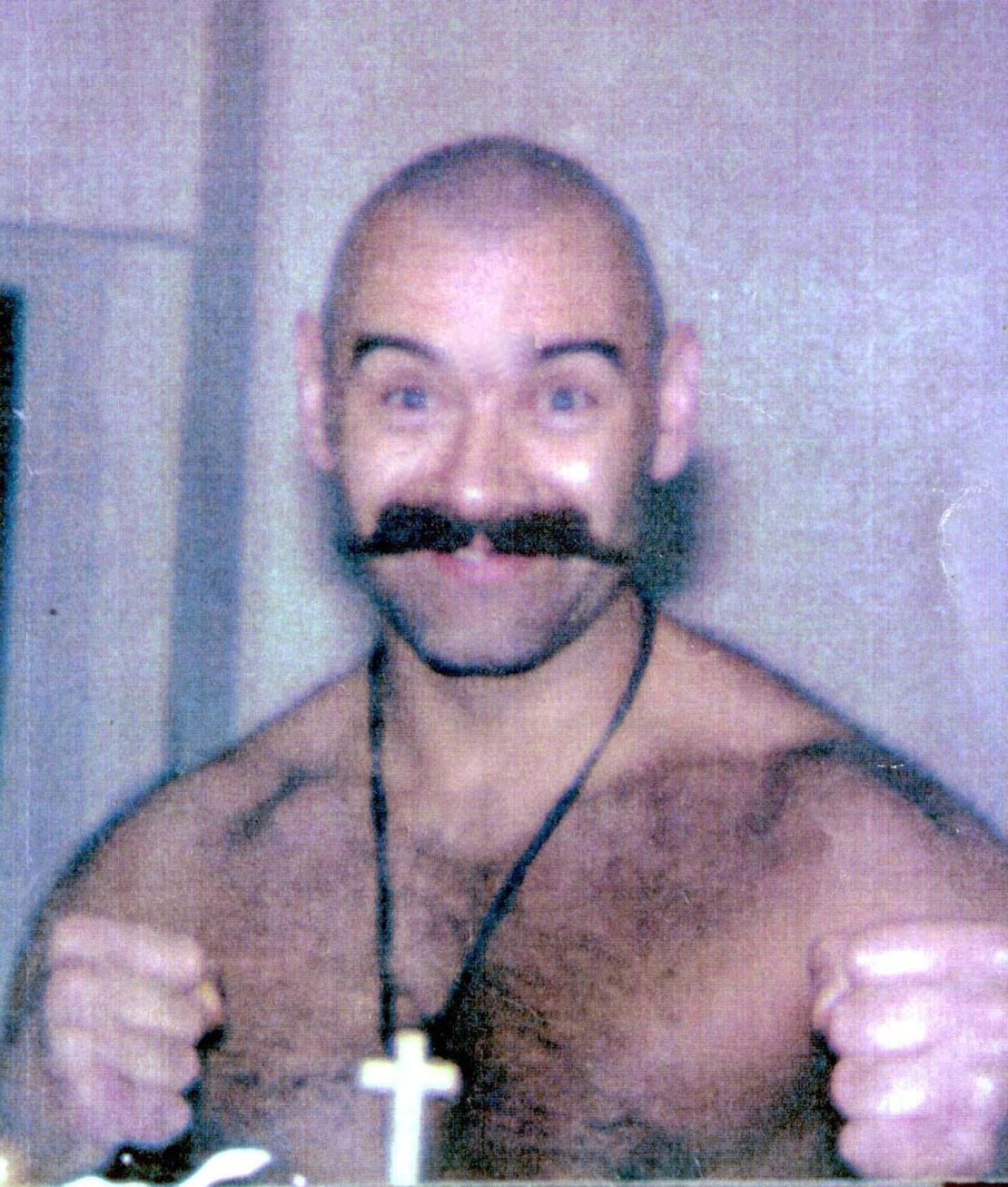

Forty years in prison has had a curious effect on Charles Salvador.

More commonly known as Charles Bronson, the man born Michael Peterson was once dubbed “Britain’s most violent prisoner” by the nation’s tabloids. Incarcerated in 1974 for armed robbery, a succession of incidents thereafter, including assault and holding prison staff hostage, saw Salvador accumulate extra jail time. Eventually he received a life sentence in 2000.

However today Salvador claims he is a reformed character – albeit one who remains in solitary confinement in a category A high security prison. The reason? He says he is a “born again artist.”

“[Art is] the one thing that he [wants] to continue and be remembered for” says Lorraine Etherington, secretary of the Charles Salvador Art Foundation and Salvador’s former fiancée.

The weight of history could make that a tough ask. Salvador’s purported antics have been a mainstay in the British press for years. Moreover “Bronson,” a film starring Tom Hardy, immortalized many of these incidents, while embellishing others.

Nevertheless, in spite of his notoriety, Salvador has found an audience.

Life in solitary

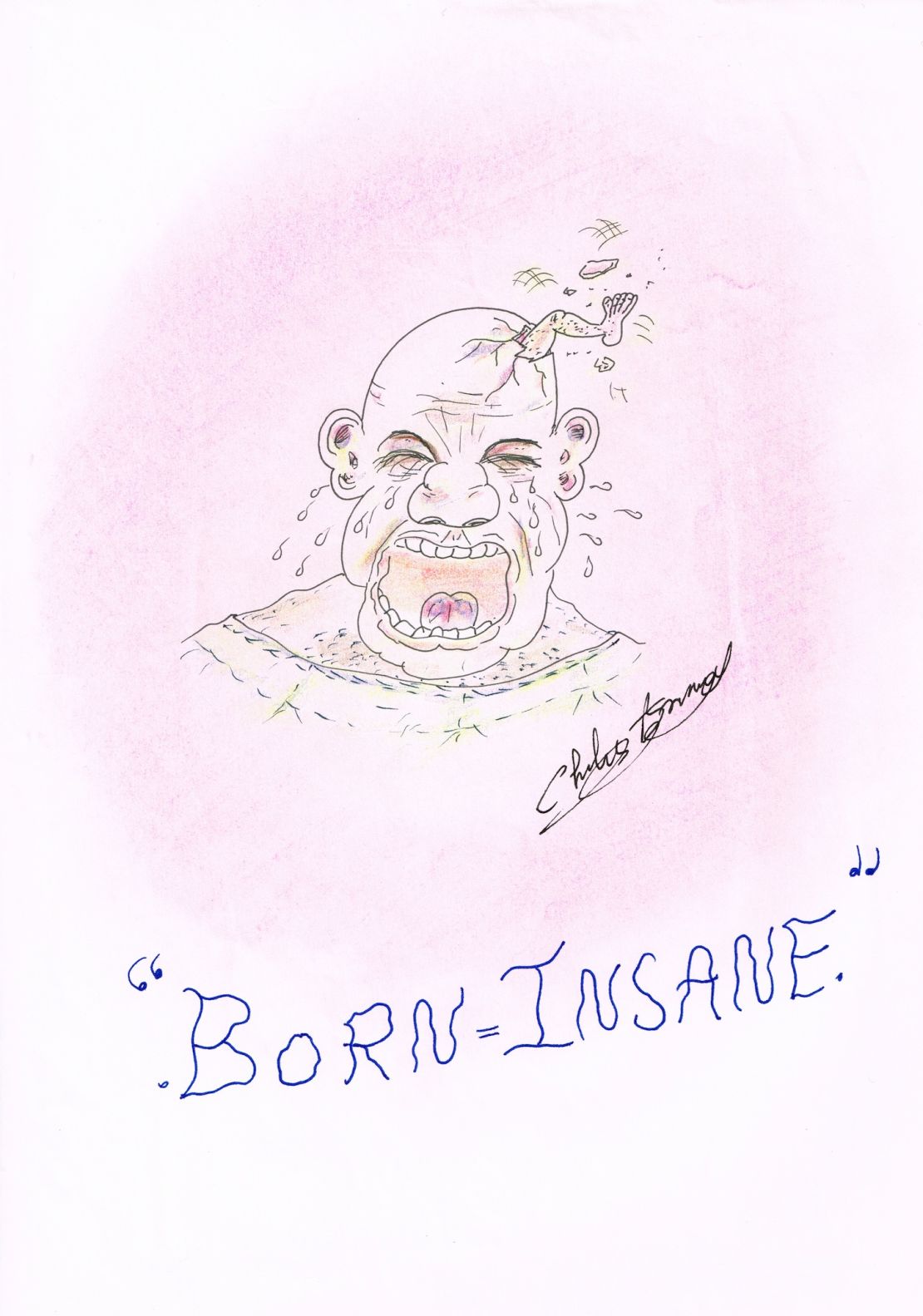

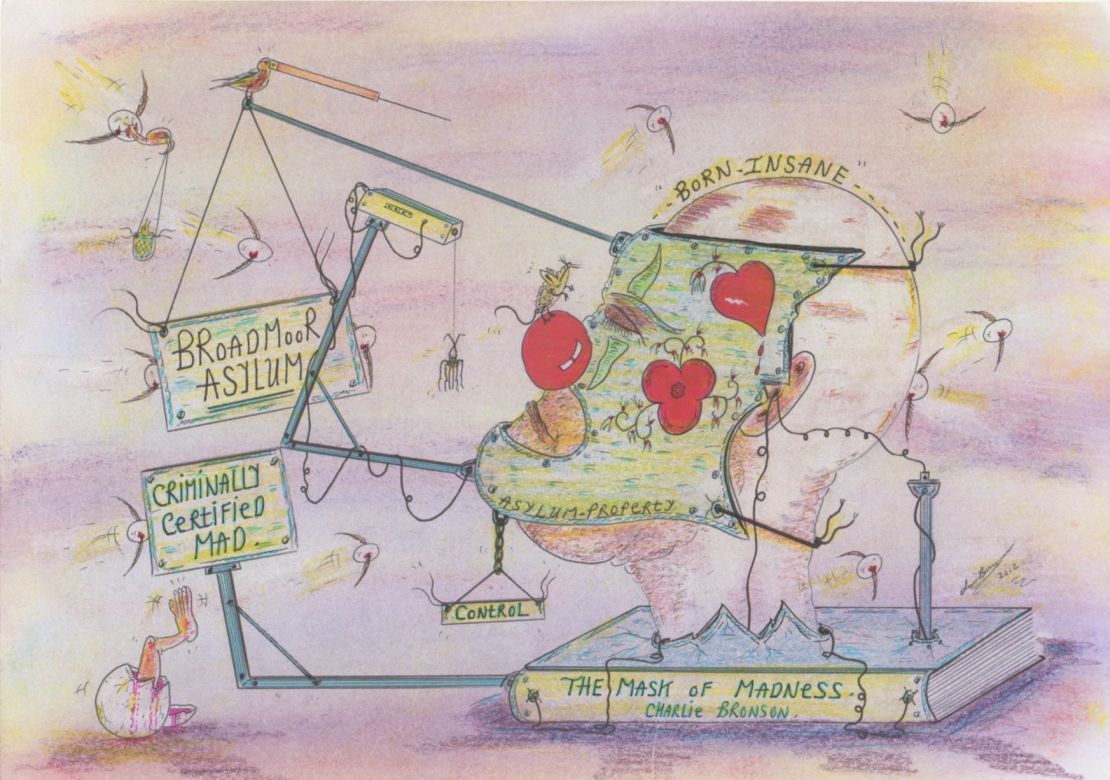

Since the mid-1990s Salvador, who is locked up for as many as 22 hours a day, has created thousands of paintings, pastels, caricatures and doodles.

Restraints and surveillance cameras are common themes, as is the motif of a winged hypodermic needle – a representation, Etherington says, of “liquid cosh”, an incapacitating drug administered in secure hospitals in the 1970s and ’80s. Drugs, she explains, were used “as a matter of course” at Broadmoor, Rampton and Ashworth hospitals – all of which Salvador had visited.

“You have to realize that his artwork is a telling of his time,” says Etherington. “A lot of people find it challenging and a lot of people find it frightening, but […] it’s what’s in his head. He can only draw from what he sees and what he knows, and what he’s had around him for the best part of 40 years.”

Etherington insists that rather than convey any madness on Salvador’s part, his work reflects “the madness he has come in contact with” – both in terms of people and the penal system.

(But this is, she says, only her interpretation. Salvador is unable to speak to the media and has little opportunity to rebuff what critics read into his work.)

There are influences to be found too, she argues, sourced from art books sent in by well-wishers.

When Cezanne’s “The Card Players” sold for a record amount in 2011 Salvador drew a version of his own. Gaping mouths and contorted bodies in Hieronymus Bosch’s “A Violent Forcing of the Frog” are referenced in Salvador’s work, while Francis Bacon’s triptychs are riffed on in the multiple personalities of “Triptophrenia” – controversially displayed on London’s Underground network in 2010.

The Death of Bronson

James Elphick, founder and curator of underground art organization Guerrilla Zoo, has hosted work by Salvador in recent years, organizing “The Death of Bronson” in 2015. Authenticity is part of the appeal, he says.

“Charlie has lived many of [the experiences he draws], which gives his work credence and respect due,” Elphick says.

Criminals who turned to art

“The art he produces is a fascinating insight into the mind of a man who’s been through so much chaos in his early life and [is] often quite philosophical and engaging… It’s not just landscapes of madness, but flowers, sharks, birds, teddy bears and dreams of being on a desert island sipping cocktails – the ever seemingly impossible bid to escape and taste freedom.”

Prior to “The Death of Bronson,” in which Salvador renounced violence and his old identity, many of his works were sold at auction as part of the purge. Other creations have also been sold with proceeds going to charity.

Etherington says that between charitable work and private donations, Salvador has raised approximately $366,000 for good causes.

‘This isn’t just a hobby’

Mike Rolfe, chair of the Prison Officers’ Association in the UK, sees Salvador’s artistic verve as a positive step.

“We take a view that people should be rehabilitated, so it’s always nice to see people turn a corner,” he told CNN. “Because obviously Charlie is so high profile, it’s bringing to the fore some of that good work that prison officers do.”

The Koestler Trust, which holds annual awards for the best art by British offenders, has recognized Salvador’s work on multiple occasions.

While the Trust says it is unable to comment on individual prisoners, chief executive Sally Taylor says winners “are rightly proud of their achievements – and they should be, as the awards are judged by leading contemporary artists.”

(Grayson Perry and Sarah Lucas have acted as curators in the past, and Anthony Gormley will assume the role in 2017.)

“As Dame Sally Coates said at the launch of her recent review of prisoner education, the arts play a critical part in building self-confidence and self-worth.”

Self-definition too, suggests Etherington. At Salvador’s latest parole hearing the inmate included drawings in documentation presented to authorities.

“This isn’t just a hobby,” says Elphick, “this is what he’s been focusing [on] and creating for the last 18 years.”