Editor’s Note: John McIlroy is Deputy Editor of Auto Express and Carbuyer.

Story highlights

Some of the most common elements to car design have accidental origins

Scroll through the gallery above for top innovations

In a world where new, clever ways of using tech and the cloud are being unveiled on an almost daily basis, the speed of progress on the automobile can look a bit glacial by comparison.

In the most basic terms, the cars being sold today are similar to those introduced at the start of the 20th century: a combustion engine driving the wheels through some sort of gearbox, with steering controlled by a wheel at the front of the cabin.

Searching back through history reveals, however, that while many of the car industry’s ideas are not new at all, it has taken quite a bit of ingenuity to turn them into something people are willing to pay money for.

You may think that Tesla could claim credit for introducing the first viable electric car. But Toyota could point to the nine million-plus hybrids it has shifted since 1997.

And if you go back far enough, you’ll find that Thomas Edison and Henry Ford had a jointly developed electric vehicle back in 1913.

The car industry, you see, is full of examples of innovations that went nowhere until someone – quite often not the original inventor – worked out how to industrialize the idea. Take the four-wheel drive, a technology that’s now synonymous with premium, upmarket vehicles, particularly SUVs.

Four-wheel drive

The idea of driving all four wheels – with benefits in safety and performance – was first introduced as long ago as 1903 (on a Dutch sports car called a Spyker).

Crazy concepts: The wackiest ideas to hit the autos industry

But for much of the 20th century it remained a technology largely restricted to tractors and military vehicles like the Land Rover and the Jeep, and occasional oddities from small-scale manufacturers.

Read: Land Rover Defender ends production after seven decades

Audi changed all that with its Quattro, a luxury sports coupe introduced in 1980. Sales figures for the car were relatively modest, but highly tuned competition versions of it dominated the sport of rallying.

Four-wheel drive suddenly became not just useful, but actually attractive.

Audi still calls its four-wheel drive system “quattro,” and these days you’re almost as likely to find a 4WD system on a luxury coupe like a Bentley or an executive saloon from BMW as you are a rugged Jeep or Land Rover.

READ: Surreal scenes of autos gone rogue

Many of these cars - and most of them, if you’re an American buyer, will save you the bother of changing gear. But this concept is further proof of how good ideas can take time to work their way through to customers.

There was something akin to an automatic gearbox as early as 1904, but that concept was chronically unreliable and it would be another 35 years before General Motors was able to introduce Hydra-Matic, the world’s first mass-produced auto transmission.

Breaking barriers

There are examples of bold innovations that have been a hit in their own right. Sir Alec Issigonis’ original Mini broke the rules on how small and cheap family transport could be, and even though it made its debut back in 1959, its influence in how small cars are packaged can still be felt today.

Right now, the car industry is caught up in an arms race on who can deliver the best fuel efficiency. Volkswagen, for example, has petrol engines that can shut down cylinders when you’re cruising along, in order to save fuel.

Connectivity is key, too; car manufacturers know we’re constantly checking smartphone screens, so anything that links the vehicle to that interface is seen as a potential reason to buy. The latest Land Rover Discovery, for example, can lower individual seats remotely using a smartphone app – handy if you know who’s traveling before you get to the car.

Read: The new breed of driverless vehicles

And on the horizon is autonomy – the ability for the driver to totally switch off when they’re behind the wheel. On this score, car manufacturers are fighting with (and in a few cases collaborating with) ‘disruptors’ – not just Tesla and a hundred Chinese start-ups, but also names like Google and Apple, who have never built a car before but are suddenly interested in exploiting the amount of ‘dead time’ we could soon end up spending in it.

The best innovation of all time?

With this in mind, perhaps the best innovation of all was one that was in fact, given away for free.

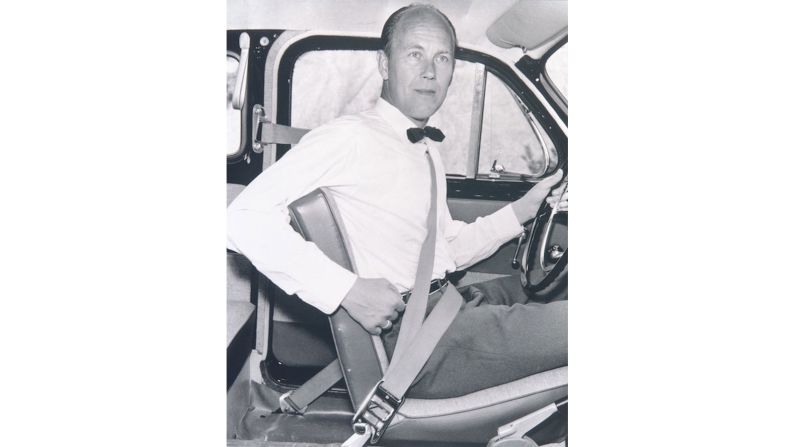

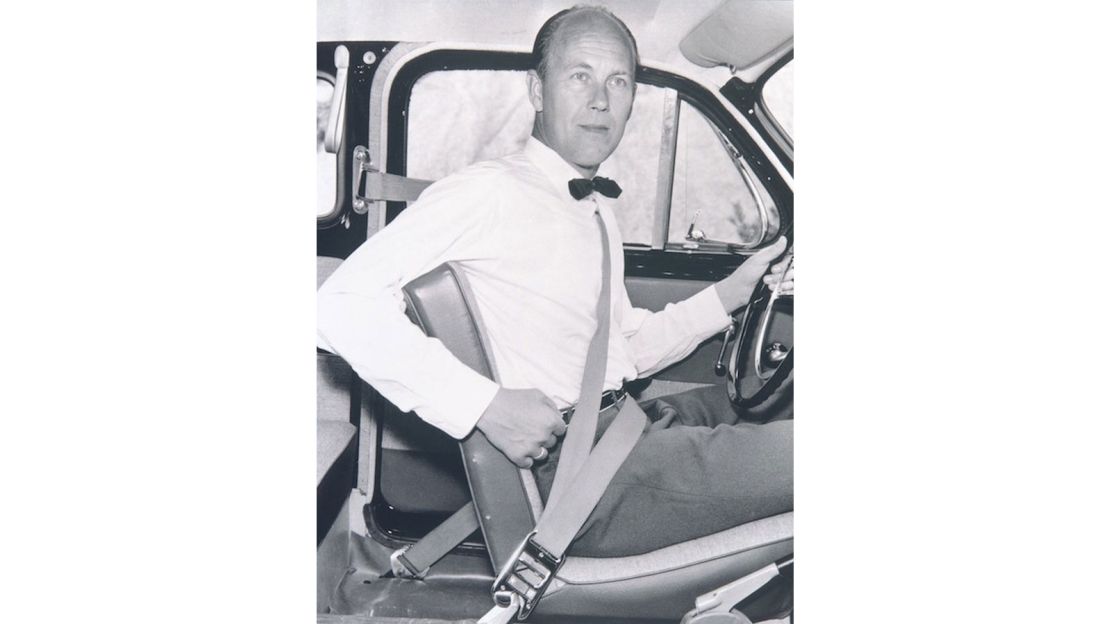

Volvo engineer Nils Bohlin had spent much of his career in aviation, and used techniques learned in that industry to come up with the idea of a three-point safety belt for cars that would cover the driver’s torso as well as their lap.

READ: The 81-year-old woman pimping BMW’s rides

Volvo introduced the set-up in 1959 and by 1963 it had made it to the US. But instead of exploiting a potentially huge advantage in car safety, the Swedish firm elected to open up the patent so everyone else could offer it too. Millions of lives have been saved by the modern seat belt as a result.

Indeed, the only automotive innovation that’s really beyond argument (and even then, only just) is the actual car itself.

Brakes made from a shoemaker

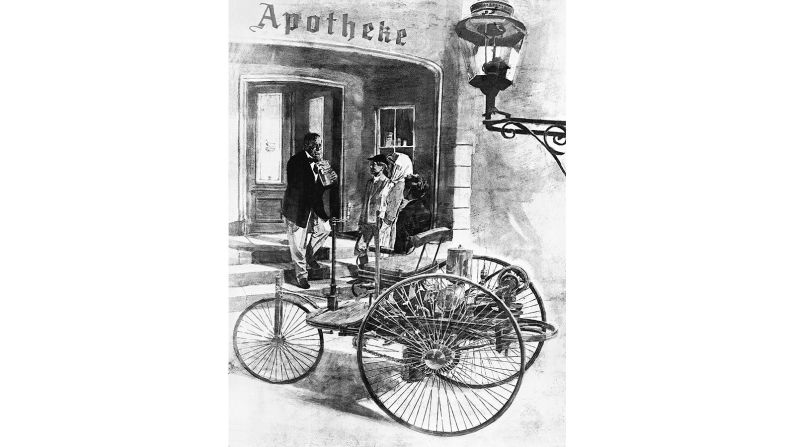

Karl Benz was awarded a patent for his ‘“Motorwagen” in 1886, and by 1888, his wife – who had actually paid for the development process, but who wasn’t allowed at the time to own the patent – felt confident enough about the vehicle to take it on a journey of around 60 miles.

She innovated en route, in fact, by getting a shoemaker to nail leather onto the brake blocks and invented brake linings as a result.

READ: ‘World’s first sports car’ sells for $657K

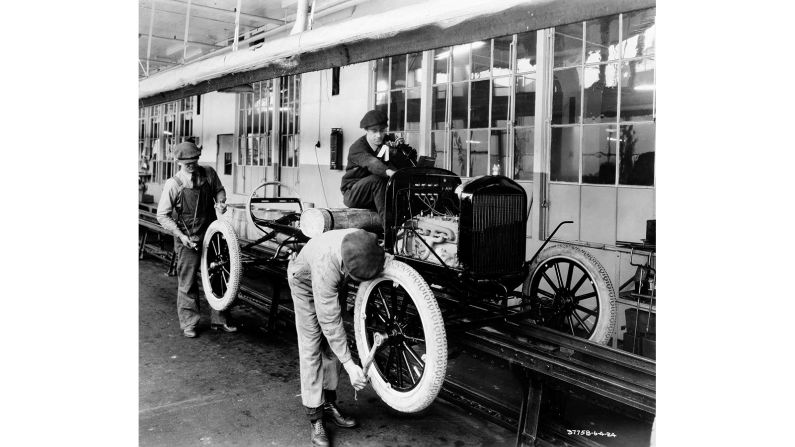

Even then, Benz’s creation was made in tiny numbers. Once more, it took another man, Henry Ford, to work out how cars could be mass-produced.

His assembly line technique allowed cars to be build in an eighth of the time required previously – so they could be made more affordable, as well.

By the time the factory in Dearborn, Michigan had knocked out its 10 millionth example in 1924, half of the cars on the planet were Model Ts.

Proof positive that innovation is all well and good, but a subtle improvement to a good idea can make all the difference.