A new 99-domed mosque in Australia is attracting attention for its bold, brutalist design. But the architect behind the project, Angelo Candalepas, is hoping that his creation can do more than win plaudits – he wants it to help improve interfaith relations in the Sydney suburb of Punchbowl.

Scheduled to open in time for Ramadan this May, the mosque has been designed to feel welcoming to the whole community, regardless of religion.

“The courtyard enables all people to embrace the use of the building,” Candalepas said in a phone interview. “The doors are absolutely directed to the street front, such that it will always have its doors open to the people.”

At a September event called “Meet the Aussie Mosque,” the unfinished building was opened to the public as part of the Sydney Architecture Festival. Architects led tours of the mosque, while members of Punchbowl’s Muslim community spoke to visitors about their faith and the fundraising drive behind the A$12 million ($9million) project.

“We wanted to bring the great work of the modern mosque out in the open, and to normalize the building as a work of architecture,” said the festival’s director, Timothy Horton, in a phone interview. “The Punchbowl mosque is a modern architectural masterpiece. It is set to be one of the new icons in Sydney’s west, one of the most cultural diverse and fastest growing parts of Australia.”

Reimagining mosque design

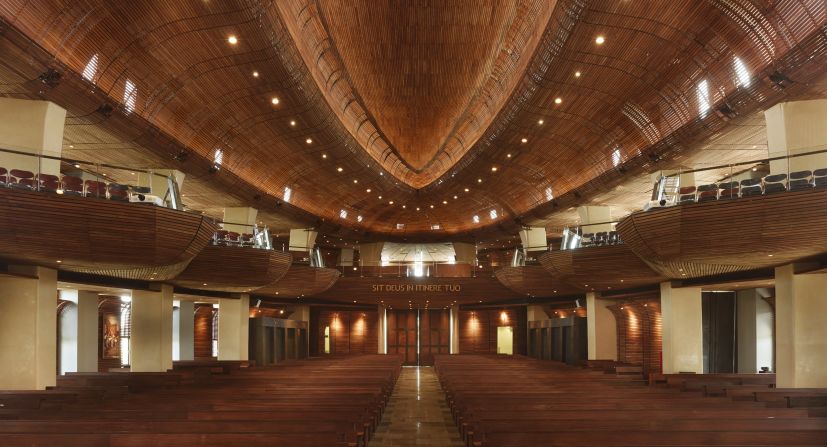

Candalepas’ eye-catching concrete design also challenges preconceptions about how a mosque should look, according to Horton.

“The outside has been totally reimagined,” he said. “Gone is the central dome with four minarets planted like garden stakes at the corners. Candalepas’ mosque strings (together) smaller spaces, like washrooms, along the boundary while scooping light in as you would see in a high-end art gallery.”

Commissioning a contemporary design (and a high-profile architect) was a response to the reported difficulty of obtaining planning permission for new mosques, according to the vice president of Punchbowl’s Australian Islamic Mission, Zachariah Matthews.

“Our main concern, initially, was, ‘How do we get approval given that other projects have encountered many obstacles?’” he said.

In recent years, public opposition has delayed or permit the construction of a number of proposed mosques in Australia.

Last year, permission for a new mosque in the Gold Coast suburb of Currumbin was denied on the grounds that it was “too big” following a high-profile opposition campaign in which a councilor reported receiving death threats. Another proposed mosque in Victoria only got the green light this July after three years of legal hurdles and ongoing media attention. A Facebook group opposing the building has almost 70,000 members.

Yet, Matthews said that plans for his mosque were unanimously approved by the local council. Of Australia’s more than 340 mosques, almost half can be found in Punchbowl’s state of New South Wales.

An act of faith

Finding a religious architect was another key priority for Punchbowl’s Muslim community, according to Horton.

“It gave them confidence that the foundations of their faith would be incorporated into a building that may not appear … to be a traditional mosque, but would retain all of the meaning that is so much a part of sacred spaces,” he said.

Candalepas, who is a Greek Orthodox Christian, said that he hesitated when first approached by the Australian Islamic Mission in Punchbowl a decade ago.

“I never imagined myself as someone who would build a mosque,” he said. “It wasn’t anything negative (but rather) a sense of not having been aware that I could create something for a faith that I knew nothing about.

To find inspiration, Candalepas traveled to Ahmedabad and Agra in India while forming his vision of a mosque that could represent Australia’s Muslim community.

“I wanted a building that looked both ways – forwards as well as back,” he said. “There’s no point in ignoring history – that wouldn’t make it relevant.”

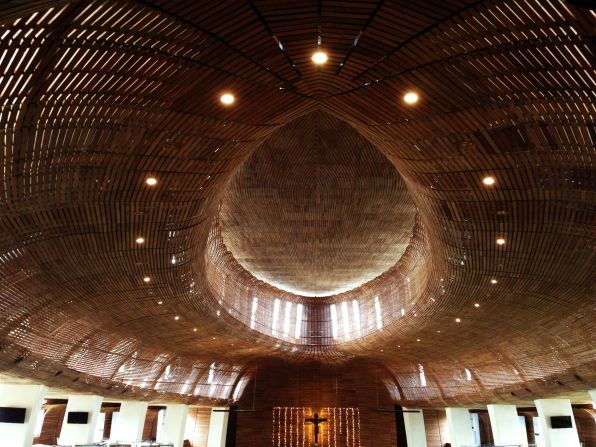

The traditional dome is still present in his design, but it has been reimagined as 99 half-domes cascading down from a larger, central one. In January, calligraphers will arrive from Turkey to spend a month inscribing the domes with Allah’s 99 names in Arabic.

Candalepas said that much of enthusiasm for the project stems from the building’s longevity. After hearing that the brief called for a lifespan of 300 years, he proposed 1,000.

“In the past, people knew it was important to create things that would last,” he said.

Community architecture

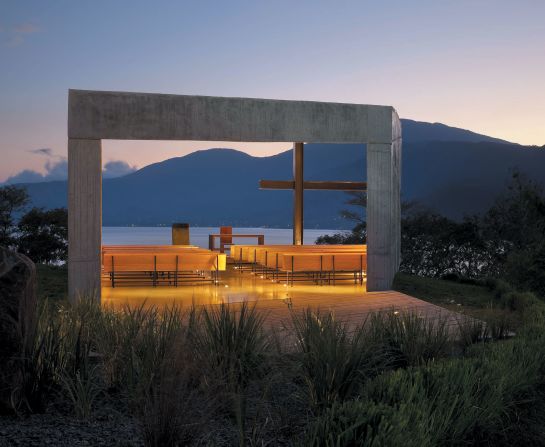

By eroding fear and suspicion through design, Candalepas follows in the footsteps of Pritzker Prize-winning Glenn Murcutt, the architect behind another new mosque in Melbourne. Opened in the suburb of Newport this year, the building’s doors are made entirely of glass.

“We choose glass because we wanted the building to be very transparent,” explained designer Hakan Elevli, who collaborated with Murcutt on the project. “People walking past on the street can see what’s going on inside. We wanted to show that there is nothing to hide.

“The Newport mosque also has a library, cafe, women’s community center and a visitor’s center which, like the mosque itself, are open to all.”

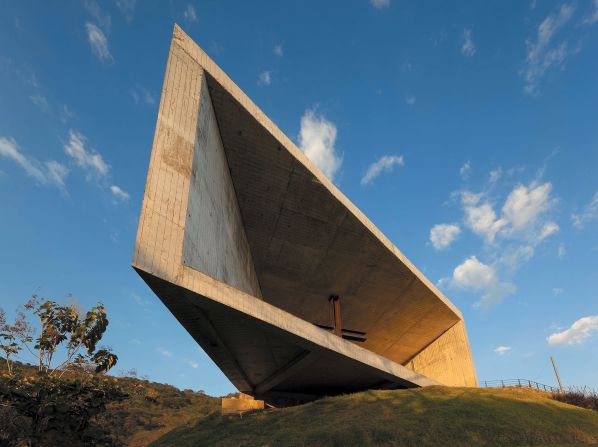

Murcutt’s design eschewed the more obvious Ottoman and Arabic influences found in many Australian mosques. The minaret is a soaring concrete wall, while the roof is composed of 96 triangular lanterns. Colored glass filters the light, acting as sun dial and a substitution for domes, with shades of red, green, gold and blue representing those typically used in mosaics.

“When a lot of people look at the building, they see it as a contemporary building and not something normally associated with Islamic architecture,” said Elevli. “But as soon as you walk inside, you see that it’s Islamic, with Arabic lettering and the ‘minbar’ (pulpit).”

Are these the most beautiful places in the world to pray?

The mosque was also designed to promote integration and demonstrate the diverse make-up of Australia’s Muslims, who account for almost 3% of the country’s population. Typical curves and arches were abandoned in favor of straight lines and linear shapes – features often found in Australian architecture.

“More than anything, (Newport’s Muslim community) wanted something Australian,” said Elevli. “They wanted to show non-Muslims that a mosque can be something that relates to the Australian way of life.”