Seeing the new India through the eyes of an invisible woman

Kolkata, India (CNN) — Not far from the place I once called home stands one of India's glitziest shopping malls. By day, the massive building dwarfs every structure around it. At night, a dizzying display of lights cruelly exposes the surrounding shops and houses grown green, brown and weary from pollution and rain.

Inside this shining behemoth called Quest, Kolkatans with fat pocketbooks spend their rupees on luxury foreign brands such as Gucci and eat at Michelin-star restaurants.

Outside, life's cadences remain much the same for people like my friend Amina.

She lives in a slum in the shadow of Quest.

She is part of a faceless, often-cited statistic: About 60% of India's nearly 1.3 billion people live on less than $3.10 a day, the World Bank's median poverty line. And 21%, or more than 250 million people, survive on less than $2 a day.

Like other middle-class Indians, I grew up knowing little about poor people's lives. We moved in separate worlds, which, in my mind, only grew further apart as India lurched ahead as a global economic power. The rich got richer; the poor mostly stayed poor. And the gap widened.

Today, the richest 10% in India controls 80% of the nation's wealth, according to a 2017 report published by Oxfam, an international confederation of agencies fighting poverty. And the top 1% owns 58% of India's wealth. (By comparison, the richest 1% in the United States owns 37% of the wealth.)

Another way to look at it: In India, the wealth of 16 people is equal to the wealth of 600 million people.

Those startling numbers about my homeland make me think of it as almost schizophrenic.

One India boasts billionaires and brainiacs, nuclear bombs, tech and democracy. The other is inhabited by people like Amina. In that India, almost 75% still lives in villages and leads a hardscrabble life of labor; only 11% owns a refrigerator; 35% cannot read and write.

I am meeting Amina on this day because I rarely see policymakers or journalists talk to people like her about India's progress. Kolkata's Quest Mall is one representation of India's economic success, and I want to ask Amina what she makes of it.

Kolkata's Quest Mall boasts upscale shops and restaurants, but outside life's cadences have changed little over the years.

My changing homeland

I have known Amina since 1998, when she began working at my parents' flat. She walked every morning -- sometimes in rubber flip-flops, sometimes barefoot -- from her room about a mile and a half away. She arrived around 10 to wash the pans from the night before and the dishes from breakfast. She scrubbed hard, and we often joked that we could taste the grit of Ajax in our fish curry.

She dusted the furniture, finely covered with a layer of Kolkata dust even though the day was still young, and hand washed clothes too delicate for our rustic washing machine.

Amina was probably then already well into her 60s, though she used to say: "I think I am 50." She didn't have a single piece of documentation, but her family insisted she was born before India gained independence in 1947.

She stood not much taller than my wheelchair-bound mother, paralyzed from a massive stroke. But no one was fooled by Amina's small stature; she was steely from years of domestic labor.

My mother adored her and even after my parents died in 2001 and I sold the flat, I sought out Amina on every trip home to Kolkata.

On one visit, I learned her husband, Sheikh Fazrul, had died, and as she grew more feeble, she had a hard time keeping jobs. I always tried to slip her a few rupees, but she never took the money without insisting on "earning" it. She offered a massage or pedicure in exchange.

I visit India often, partly because I am different from many of my Indian-American peers who arrived in the United States as young immigrants and did not look back. My parents moved back and forth from India throughout my youth, and my personal connections to my homeland run deep.

But there is another reason as well. Increasingly I've grown intrigued by India's metamorphosis from a poor "Third World" former colony to a global power.

I am aware, too, that a Westerner's view of India is often clichéd -- it's a land of corruption, bus crashes, pollution, arranged marriages and colorful festivals. It may still be all of that, but there are so many new dimensions to Indian society.

Half of its population -- that's 600 million people -- are under the age of 25. A nation long known for poverty and hunger is experiencing a rise in obesity in urban areas. And the information technology sector, a primary driver of Indian growth, is also responsible for pushing centuries-old traditional trades to extinction.

The changes force me to reacquaint myself constantly with the land of my birth.

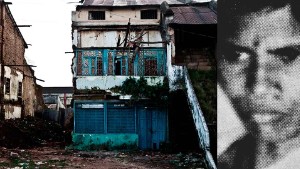

Amina walked from a room in a slum to the author's flat in Kolkata, where she dusted furniture and washed dishes.

Beyond the beautiful

On this afternoon, I am eager to see how Amina has fared since our last meeting. I navigate a dark, maze-like alleyway that leads to Amina's one-room abode.

The air is smoky from coal-burning stoves, the sulfuric smell colliding with the perfume of onions, garlic and garam masala in the woks of women cooking lunch.

There's no indoor plumbing, and I see teenage girls fetching water in red plastic buckets from an outside tubewell. There's a common toilet, but men and women bathe out in the open.

I think of Katherine Boo's best-seller, "Beyond the Beautiful Forevers," an exquisitely detailed chronicle of life inside a Mumbai slum. What I took away from that book was a realization that poor people in slums such as Amina's are not necessarily jostling to become India's next billionaire. They just want to fare better than their neighbors, move up a notch, however small, in the money ladder -- not unlike any of us who strive for a better house, a shinier car, a good education for our kids.

But Amina never moved up and that is perhaps her great sadness; that she was widowed by a man who she believes had neither the verve nor the physical strength to improve his lot in life.

I spot Amina's granddaughter, Manisha, and she takes me to her. Amina's room is cave-like, with no windows. A wooden cot sits up on bricks to keep it dry when the monsoons intrude. A television set, circa 1990, perches precariously on a shelf. Scratched aluminum pots adorn a wall facing the bed as though they were priceless works of art.

For this, Amina pays $2 a month, about what she used to earn at my parents' house. Rent controls in the slum are the only reason her son-in-law, who lives nearby, can afford to keep her here. She shares the space with her grandchildren and, sometimes, a daughter who lives in Kashmir.

People like Amina inspire economists such as Devinder Sharma to push India to take an alternate path to development. He is a bit of a firebrand, on a crusade to highlight the plight of India's poor. He argues that India's tax structure and other government incentives benefit its wealthiest industrialists -- such as billionaire Sanjiv Goenka, the builder of Quest Mall.

In business circles, Sharma is called anti-development. Indian entrepreneurs have their own ideas on why there is enormous inequality. They point to government corruption and inefficiency: India still ranks high on Transparency International's corruption perception index, at 79 out of 176 countries, with 1 (Denmark) being the least corrupt. (The United States ranks 18.)

Near the upscale Quest Mall in Kolkata, the poor struggle to survive on the streets.

Other factors feed the wealth gap, adds Raj Desai, an expert on economic development at Georgetown University. It matters whether you are a man or a woman, whether you belong to the untouchable caste. It matters where you live -- in a remote village or in an urban center. Someone like Amina, Desai says, is better off than the rural poor.

I take off my shoes and walk into Amina's room. She is on the floor and cannot stand up by herself to give me her usual warm hug. She gained weight after arthritis took hold of her body and limited her mobility. She's in her 80s now and has managed to live beyond the average age of death in India: 68.

I sit down on the cement floor to meet her eyes. I had told her ahead of time that I would be taking her on an outing.

"It's so good to see you," she says. "Where are we going today?"

"To another world," I say.

'Where have we come? It's so clean'

Amina hobbles to another room to get dressed and returns wearing a new orange and white printed cotton sari, the kind I know will run for at least the first dozen washings. She is barefoot, the cracks on her feet blackened by dirt.

We walk to the road and get into the car I have borrowed. She tells me she has ridden in a car or a taxi a few times in her life, mostly when her employers arranged for the ride.

The car meanders down the road that Amina traversed by foot every day. Finally, we arrive at Quest, where the juxtaposition of old and new is jarring.

Outside the mall, I watch Tapan Datta crack an egg at his roadside food stall, as he has for the past 15 years. He recently raised the price of his omelet to 10 rupees, or 14 cents. Inside the mall, a veggie quesadilla at the American chain Chili's costs 25 times more.

Quest hasn't really hurt his business that much, Datta laughs, because his customers can't afford anything in there. It's beyond the realm of most Kolkatans, including Amina.

When we try to step out at the main entrance, a security guard rushes toward us.

The mall was another world to Amina. She'd never been inside before.

"No entrance for her," he says in Hindi. "No one can go in without shoes."

I see the sign on the glistening glass doors: "Rights to admission reserved."

I tell him Amina requires a wheelchair, an embellished truth that allows us to foray into the mall without Amina's feet touching the sparkling Italian marble tiles. Amina's eyes grow big. Her head swivels from side to side, as though she were watching a tennis match.

"Where have we come? It's so clean," she asks. She has seen Kolkata's newest mall from the outside but never dared go near it.

It's midafternoon on a weekday, and there isn't the normal crowd at the mall. I see mostly women and teenage girls bopping in and out of stores like Vero Moda and Michael Kors.

I wheel Amina into the Gucci store. The salesclerks look at us in wonder: Why is a middle-class woman catering to a poor one?

"How can I help you?" asks a woman behind the counter.

I tell her to ask Amina. For a moment, the woman (she did not want to give me her name) does not know how to react but then asks politely: "May I show you a bag?"

Amina points to a silvery, buttery leather concoction.

We ask the price. "It's 1.25 lakhs," the clerk tells us. That's 125,000 rupees or $1,865.

I wait for Amina's reaction, but there is none. She cannot even fathom the amount. It's as abstract as "gazillion."

In America, few people can afford to drop almost $2,000 on a handbag. But poor people there can at least walk into a mall and grasp what it would take to pay that amount. They could even possibly save enough to buy it one day.

It would have taken Amina at least 25 years to earn that amount.

In a way, I am relieved she cannot comprehend the price. I worry she might have felt humiliated otherwise, and that is far from my intention.

'I have come from hell to heaven'

How to solve this massive inequality is the million-dollar question being argued all over India. Does national growth need more time to deliver its magic, or is India's economic formula flawed?

The country's growth in the last 15 years or so has largely been jobless growth, which some analysts say exacerbates the problem.

French economist Thomas Piketty, who authored the seminal work "Capital in the 21st Century," caused a stir by suggesting higher taxes for the rich. One Indian media outlet labeled him "Modern Marx."

Among the biggest problems, of course, is a lack of decent education and public health. I'm not sure anyone has all the answers at this point, but I'd like to see enough progress so that people such as Amina, who worked hard all her life, don't have to die in poverty.

Desai, the Georgetown economist, talks about establishing a pension system in the vein of Social Security to provide an immediate lift for millions. To that end, Prime Minister Narendra Modi's government has launched a government pension plan, though it is not without criticism.

It's too late anyway for Amina. As part of India's unregulated domestic work force, she never had any protection. Only now are some Indian states passing laws to shield such workers from exploitation.

I take Amina to the mall's food court on the top level, and she orders a heaping plate of chow mein. She's never seen chopsticks before; nor has she used a fork. I tell her it's OK to eat with her hands. She doesn't care for green peppers, fishes them out of the noodles and pushes them aside.

Again, I feel the burn of many eyes upon us.

"What do you think of this place?" I ask her.

"I have come from hell to heaven."

After a few minutes of silence, she says, "I suppose now you will have to take me back."

In the car, Amina places her hand on mine.

She tells me her parents died when she was a child, and an aunt brought her from her native Allahabad to Kolkata. She started working at an early age and toiled her whole life until her body gave in. Now she lives day to day at the mercy of her daughters and sons-in-law.

"Aami garibmanush aachi, didi."

I am a poor person, she says in broken Bengali.

"And I will always be a poor person," she says. "There is no way out for people like me."

Her words make me terribly sad.

Beyond the data and the academic discussions of what it means to be poor in India, I know this: There is no version of the American dream in Amina's world. She would not let herself dare to hope.

We make our way back through congested lanes teeming with street life. Here you can buy almost anything you need, from syrupy fried sweets called jilebis to the blood pressure pills you'll need if you eat too many. I look at a stall selling leather handbags.

They hang from hooks on a wooden pole, their black leather dulled by sun and dust.

These are cheaper than Gucci, only $3 each. I ask Amina if she would like one.

"I can afford these," I say.

"What will I do with a bag?" she asks.

After a lifetime, she has nothing.

I drop her off at the entrance to the slum.

"Are there poor people in America?" she asks before getting out of the car.

I tell her there are people everywhere who are in need.

"Do they go shopping at malls?" she asks.

"Sometimes," I respond. "See you next time, Aminaji."

"Maybe," she says. "If I am still here."

Postscript

I took Amina to Quest Mall at the end of 2015 and last saw her 10 months ago. I inquired about her shortly before the publication of this story and learned that her slum has been bulldozed to make way for a high-rise residential building. Flats in that part of Kolkata can sell for $150,000 or more. I also learned that the landowners relocated Amina and her family to another slum. I am still trying to find her.