The final stage of the presidential race began during a hurricane, thirty-two days before the election. There was hard rain in Florida, wind lashing the palms, an exploding power line giving off showers of phosphorescent sparks. The Atlantic Ocean washed out roads and poured into living rooms. Nature imposed on everyone, even future presidents, and October held unpleasant surprises for Clinton and Trump alike. Sex, lies, video, federal agents and Russian hackers: In a campaign that defied all expectations, this would be the wildest month yet.

On Friday, October 7, the leaves were turning in New York. Clinton left her home in Chappaqua for the Doral Arrowwood hotel in Rye Brook to prepare for Sunday's debate. Trump held a roundtable meeting with Border Patrol agents at his tower in Manhattan and warned of an election swayed by undocumented criminals. The World Clown Association announced it would not endorse a presidential candidate but would favor the party with the best cream pies and bounce houses. Until late afternoon, it was a normal day by 2016 standards. Then the story broke in The Washington Post.

"You know, I'm automatically attracted to beautiful—I just start kissing them," Trump said in the accompanying video, a conversation from 2005 with the TV personality Billy Bush on an "Access Hollywood" tour bus. "It's like a magnet. I don't even wait. Just kiss. I don't even wait. And when you're a star, they let you do it. You can do anything. Grab 'em by the pussy. You can do anything."

This election was already the greatest battle of the sexes America had ever seen. Now it became something more primitive: a study of the men in all their desperation. For Clinton, there was something familiar about this. She knew some men couldn't control themselves, or wouldn't, anyway, and she'd spent decades facing the consequences. For all the grief it caused her personally, male sexual misbehavior had not been entirely bad for her career. It had not been entirely good. Twenty-one days later, it would alter the race yet again.

The most important variable in the race was Trump's ability to control himself. He did not need to do this in the primaries, because his unregulated impulses appealed to the faction of Republicans who wanted political correctness destroyed at any cost. But he needed to in October, to reassure the Republicans and independents who were grasping for some reason to believe he had the judgment to be their president. The "Access Hollywood" video, which Trump dismissed as mere "locker-room talk," showed an alpha male who'd become rich and famous by answering to no one but himself. This Trump was struggling to build a winning coalition. He was having trouble persuading the Mormons in Utah and Nevada, the suburban women outside Philadelphia, the college graduates along Interstate 4 in Florida. Becoming president would take some restraint. Which is why Republican leaders were trying to wrestle him into a straitjacket.

The video undid all those efforts. You can do anything, he had said, and eleven years later he still seemed to believe it. Never before had a major party's nominee been so unaccountable to the norms of his party and his country. In his latest rampage he would attack the Democrats, the Republicans, the free press and the very foundations of peaceful democracy. He would insinuate that women who accused him of sexual assault were not attractive enough to deserve his attention. He would threaten to sue his accusers. And the Republican National Committee would stand by him through it all.

The video forced elected Republicans into excruciating contortions. Many rebuked him in public statements. Some said he should step aside and let Mike Pence lead the ticket. And then, when Trump refused to quit, several Republicans who had unendorsed him or called for his withdrawal said they would vote for him after all. In a different year, the video might have been a campaign-ender. Not this time.

"Voters really do seem to have a pretty short memory," Navin Nayak, director of opinion research for the Clinton campaign, said in an interview. He noted that the video had dominated the news and that polls showed the vast majority of Americans, initially, were aware of it and even offended by it. But, he said, less than three weeks later, they seemed to have forgotten about it. In focus groups, Nayak said, "we were testing an ad where the Republican mother is talking about how, 'When that tape came out, and he dismissed it as locker-room talk, I realized I just couldn't look at my daughters and vote for him.' And half of the people in that focus group didn't know what she was talking about."

According to chief strategist Sean Spicer, the RNC never seriously considered distancing itself from Trump. "Our job is to get people to get out and vote," he said. "You can't then say, 'By the way, when you go into the voting booth, only do the following.' It doesn't work like that."

Had Trump confessed on tape to sexual assault? Was he trying to destroy their party? Either way, the Republicans needed him to stay competitive. His fortunes on November 8 would affect the entire party. They were all in this whirlwind together.

✦ ✦ ✦

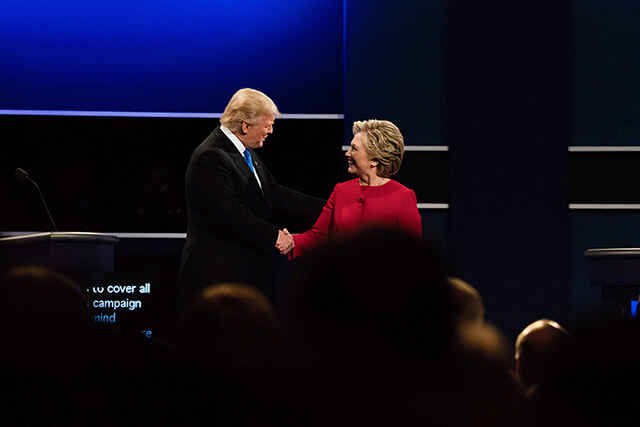

As Clinton and Trump prepared for their first debate on September 26, eleven days before the "Access Hollywood" tape surfaced, national polls showed them in a virtual tie. This was all the more surprising given that Trump's campaign seemed to be in perpetual turmoil. Republican operative Chris Wilson called it "the worst campaign in the history of modern American politics."

Several Trump campaign employees left within weeks or even days of their hiring. Most of the party's brightest political minds stayed away altogether. According to a senior Republican strategist with inside knowledge of the subject, "There was no thought, there was no planning, there was no actual campaign structure and there was no real leadership to make decisions. And some of the campaign leadership that would be strategically sitting in a room doing that is chasing the candidate around trying to get him to not tweet and say stupid things, and using up all of their bandwidth on it."

No one could control Trump. But those close to him on the campaign learned that some tactics worked better than others. Telling him "no" was a bad idea. You had to deliver advice as a suggestion, preferably accompanied by some kind of affirmation. His former aide Sam Nunberg found it effective to use flattering metaphors—comparing him to gold or marble, for instance—and then to muse about how one might sell these precious materials to the American people.

The winning formula was simple. Both candidates had consistently negative favorability ratings. Thus, if Trump could make the election a referendum on Clinton, he would win. If she made it a referendum on Trump, she would win. Too often Trump took a news cycle that could have been bad for Clinton and made it bad for himself instead. In early August, the conversation could have been about tumult at the Democratic National Committee or a claim Clinton made about her emails that received four Pinocchios from the fact-checker at The Washington Post. Instead Trump kept the negative spotlight on himself by attacking a Gold Star family.

He got smarter from mid-August to mid-September, and generally stayed out of the way during Clinton's most terrible weekend. On September 9, she insulted half of Trump's supporters by putting them in a makeshift purgatory she called the "basket of deplorables." (She quickly apologized for using the word "half.") Then she was caught on video collapsing as she left a 9/11 memorial ceremony. Her campaign offered no explanation at first, then said she was "overheated," then finally acknowledged she had pneumonia. The incident made it look as if she were hiding something again—as if she and her aides didn't trust the voters enough to tell them the whole truth. And it emboldened the conspiracy theorists who'd been saying without evidence that she was too sick to be president. How would Trump handle it? Would he act gleeful, or presidential?

"I hope she gets well soon," he said the next morning on Fox News, and Republican leaders sighed with relief.

Clinton had the opposite problem: She was too predictable, too controlled. Her speeches were average at best. Her forums on opioids or child care didn't generate many headlines, because hyperbole often drowned out serious issues in 2016. This neutralized what might have been an advantage for Clinton. Her command of policy extended to such arcane topics as the allocation of radio spectrum, but this was never going to break through in a campaign against Trump. "Our policy team, bless their hearts, are like, 'Okay, but this is what's wrong with this policy and this policy,' Clinton spokeswoman Christina Reynolds said. "And we're like, "Nope. Nobody cares. Nobody cares about the policy.'"

Every day Trump didn't make a major error, he seemed to gain support. But Clinton's aides thought she could reverse that trend at the upcoming debate.

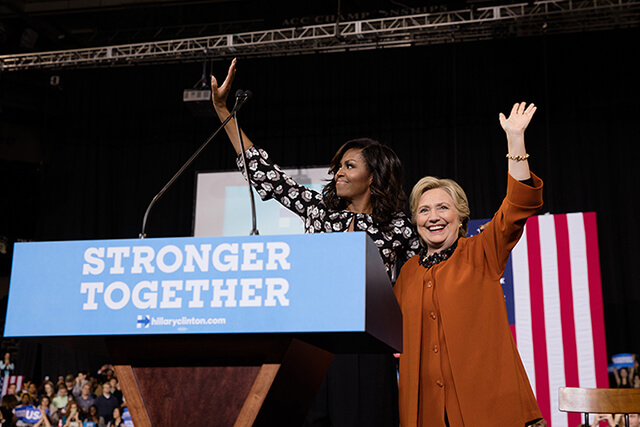

"When the American people have seen her unfiltered, even in very high-stress situations, high-wire acts in many ways, she has always been her best advocate," her adviser Mandy Grunwald said. "Each of those moments have been more important than advertising. If you look at the critical turning points of the campaign, they have been these big moments where the American people have been able to see her, not commentators' views of her, not what Donald Trump says, or Bernie Sanders, or what anyone else says about her. Just Hillary Clinton, herself, answering questions or speaking to the American people. Those have been the most critical moments of the campaign."

At campaign headquarters as the first debate approached, Clinton's aides filled a suggestion box with ideas for handling Trump. They said Clinton should wear American-made clothes and mention his company's Chinese ties, her friend, Hilary Rosen, recalled. Drop the names of foreign leaders and challenge him to identify their countries. Fight back if he brought up her husband's womanizing by reminding him of his own. Clinton's aides saw a pattern in Trump's behavior, an inability to let a slight go unreturned, and they thought Clinton could use this trait against him. If she played it just right, provoked him just enough, he might prove her case about his un-presidential temperament.

"Do you have your strategy?" Rosen asked.

"Oh, yeah, I've got my strategy," Clinton replied, according to Rosen. "I have to be warm enough that people like me, tough enough to be commander in chief, deep enough on policy that people know I have an agenda, direct on his faults. Oh, and by the way, I have to be his fact-checker, too."

Their meeting at Hofstra University on Long Island would be the most-watched debate in American history. Trump kept his preparations light. He didn't recruit a Clinton stand-in for mock debates. "He's not rehearsing canned thirty-second sound bites or spending hours in the film room like an NFL player," his spokesman Jason Miller wrote in a memo. "He will be prepared, but most importantly, he will be himself."

What that meant was anyone's guess. In Clinton's mock debates, her former aide Philippe Reines could wear a red tie like Trump, make serpentine hand gestures like Trump, lean toward the microphone and interrupt like Trump, sending the Clinton team into fits of laughter. Reines' outbursts gave Clinton the opportunity to practice keeping her own demeanor in check—which advisers said was important since she had called his temperament into question.

"You're running against someone who is erratic, wild, over-the-top," Clinton's chief strategist, Joel Benenson, said in an interview. "He's unsettling because of his being temperamentally unfit through his divisiveness, through his recklessness on foreign policy, his wild ideas on the economy. You want to in all ways be the counter to that. You want to embody the antithesis of that. Her strength is her steadiness. Her toughness, her strength under fire. You want to show that, not just tell it."

But until the debate actually started at 9 p.m. on September 26, no one knew which Trump would show up.

"Now, in all fairness to Secretary Clinton—yes, is that OK?" the disciplined Trump said at the outset, making sure to address her correctly. "Good. I want you to be very happy. It's very important to me."

When her aides poll-tested attacks against Trump, they found that voters responded most intensely to Trump's own words. Paraphrasing didn't work as well, advisers said. Clinton needed to quote Trump directly. And she did. "In fact, Donald was one of the people who rooted for the housing crisis," she said. "He said, back in 2006, 'Gee, I hope it does collapse, because then I can go in and buy some and make some money.' Well, it did collapse."

He tried to hold it together, to keep pressing the case against Clinton, but she kept throwing the bait. She said he was rich because he borrowed $14 million from his father. He called it a "small loan." She said he called climate change a Chinese hoax. "I did not. I did not," he replied, growing more defensive as the night went on. He kept leaning into the microphone and interjecting one word—"Wrong"— even when she was right, such as the time she said he supported the invasion of Iraq, which sent him into a rambling discourse about what he supposedly told his friend Sean Hannity of Fox News. He was no longer making it about Clinton, much less the American worker for whom he claimed to speak. Clinton let him waste his time. Then, after he questioned her stamina, she really set him off.

CLINTON: And one of the worst things he said was about a woman in a beauty contest. He loves beauty contests, supporting them and hanging around them. And he called this woman "Miss Piggy." Then he called her "Miss Housekeeping," because she was Latina. Donald, she has a name.

TRUMP: Where did you find this? Where did you find this?

CLINTON: Her name is Alicia Machado.

TRUMP: Where did you find this?

It was there in plain sight. In his 1997 book "The Art of the Comeback," Trump had written, "I could just see Alicia Machado, the current Miss Universe, sitting there plumply."

Clinton took control of the race by taking control of Trump—by provoking the same destructive impulses that his handlers worked to conceal. The voters ignored her when she told them who he was. They paid attention when she showed them. Alicia Machado would haunt Trump for the rest of the week. He would go on "Fox & Friends" and call her "the worst, the absolute worst"—even though the hosts never asked him about her. He would think about her in the middle of the night, open Twitter before dawn, call her "disgusting," invoke a phantom "sex tape" and generally do all he could to keep the controversy alive, just as he'd done with Khizr and Ghazala Khan after the Democratic convention. Advisers kept telling Trump to leave Machado alone and return to his message, the RNC's Sean Spicer said. But Trump couldn't let it go. The polls turned in Clinton's favor once again. The "Access Hollywood" tape emerged. The Republican Party shuddered. Trump whirled toward November, his fury intensifying.

✦ ✦ ✦

It is worth mentioning that the sun rose and set as usual that fall, and stars remained visible when the night was clear. You could say a kind word to someone and you might get one back. Dogs were still loyal, cats unknowable, and children eventually fell asleep. The morning felt good with a light jacket. Five o'clock still rolled around every Friday, and a good beverage was easy to find. In short, the presidential race was a distortion of American life, with the wholesome parts largely forgotten and the salacious ones blasting at full volume.

October 9 was the most salacious day yet. Anyone who thought Trump would be chastened by the "Access Hollywood" clip had not watched his so-called apology video, during which he said, "Bill Clinton has actually abused women, and Hillary has bullied, attacked, shamed and intimidated his victims. We will discuss this more in the coming days." He was not bluffing.

"Perhaps we'll start with Paula," he said, about ninety minutes before the second debate, in a surprise appearance with four women who had accused the Clintons of transgressions against decency. Paula, of course, was Paula Jones, who claimed in a 1994 lawsuit that Bill Clinton had lured her into a hotel room, lowered his pants and asked for oral sex. (Clinton eventually settled the suit for $850,000 without any acknowledgement of wrongdoing.)

"Well, I'm here to support Mr. Trump because he's going to make America great again," Jones said.

This brazen act of political warfare also included brief statements by Kathy Shelton, whose alleged rapist Hillary Clinton represented as a criminal-defense attorney assigned to the case in 1975 (he was convicted of a lesser charge); Kathleen Willey, who alleged that Bill Clinton sexually assaulted her in 1993; and Juanita Broaddrick, who alleged that Bill Clinton raped her in 1978.

"I tweeted recently, and Mr. Trump retweeted it, that actions speak louder than words," said Broaddrick, who had changed her story over the years about the alleged rape and was not deemed credible enough by congressional Republicans to testify at Clinton's impeachment trial. "Mr. Trump may have said some bad words, but Bill Clinton raped me, and Hillary Clinton threatened me. I don't think there's any comparison."

Afterward, a reporter shouted, "Why'd you say you touch women without consent, Mr. Trump?"

"Why don't y'all go ask Bill Clinton that?" Jones replied. "Go ahead and ask Hillary as well."

Unprecedented 2016

Michael

Smerconish

Classic Joe Biden

Here was a spectacle worthy of Jerry Springer. ("Lots of people ask where I get the guests for my show," the TV ringmaster tweeted the day before. "The answer is Trump Tower.") It continued in the debate hall at Washington University in St. Louis, where the accusers sat as close to Bill Clinton as possible. They remained seated when others stood to applaud the former president. Would Trump and Hillary Clinton shake hands when they walked onstage? No. That small civility was gone, too. His talk about her happiness gave way to threats of a special prosecutor.

"It's just awfully good that someone with the temperament of Donald Trump is not in charge of the law in our country," she said.

"Because you'd be in jail," he said.

His second performance was both more effective and more ominous than his first, although he did have to answer for the "Access Hollywood" tape.

ANDERSON COOPER, DEBATE MODERATOR: Just for the record, though, are you saying that what you said on that bus eleven years ago—that you did not actually kiss women without consent or grope women without consent?

TRUMP: I have great respect for women. Nobody has more respect for women than I do.

COOPER: So, for the record, you're saying you never did that?

TRUMP: I've said things that, frankly, you hear these things I said. And I was embarrassed by it. But I have tremendous respect for women.

COOPER: Have you ever done those things?

TRUMP: And women have respect for me. And I will tell you: No, I have not.

Yes, he did, said Jessica Leeds, Rachel Crooks, Mindy McGillivray, Natasha Stoynoff, Temple Taggart, Kristin Anderson, Summer Zervos, Cathy Heller, Jill Harth, Jessica Drake and one woman who kept her identity from the public. Following the debate, the women came forward to say Trump had indeed touched or kissed them without their consent. Trump denied it all, but his recorded boasting did him no favors. When former contestants accused Trump of barging into their dressing rooms at the beauty pageants he owned, their statements confirmed what Trump proudly told Howard Stern in a radio interview in 20"I'll go backstage and everyone's getting dressed.…You know, they're standing there with no clothes. 'Is everybody OK?' And you see these incredible looking women, and so, I sort of get away with things like that."

The Bed of Nails Theory, advanced in an interview with the Democratic strategist and CNN contributor Paul Begala, held that Trump won the primaries and remained viable through the summer partly because of the sheer volume and variety of his transgressions. No single offense stood above the others. They were approximately equal, like a thousand nails arranged in a grid on which someone can lie down without getting hurt.

Now one nail began to lengthen. Some Republicans would never leave Trump, if only because they agreed with him on certain issues, but others had lost their patience. The day after the second debate, House Speaker Paul Ryan told colleagues on a conference call that he would not campaign with Trump and could no longer defend him. Trump erupted. "Disloyal R's are far more difficult than Crooked Hillary," he tweeted. "They come at you from all sides. They don't know how to win - I will teach them!" And then: "It is so nice that the shackles have been taken off me and I can now fight for America the way I want to."

That meant accusing Ryan of sabotaging his own party. Accusing the media of conspiring with Clinton. Threatening to sue The New York Times for a story about two women who said he touched them inappropriately. And with his repeated warnings about voter fraud and a rigged system, it meant becoming the first major presidential candidate since 1860 to cast doubt on the legitimacy of the electoral process.

The sun still rose every morning, but something was changing in America. The pro-Trump conspiracy theorist Alex Jones said on the radio that Hillary Clinton and President Obama were actual demons. A woman at a Mike Pence rally said that if Clinton won, "I'm ready for a revolution because we can't have her in." In Grimes, Iowa, a staunch Republican named Betty Odgaard examined her options. She and her husband had lost their wedding chapel after refusing to host a ceremony for two men, which is to say she had never been afraid to proclaim unpopular beliefs. But this was different. Trump had left her speechless. When asked how she'd vote in November, she said, "I want to keep that between me and me."

✦ ✦ ✦

His handlers knew the question would come. If you lose, will you accept the election results? And as they prepared him for the third debate, they told him what to say. According to a senior Republican official with direct knowledge of the conversations, Gov. Chris Christie and RNC Chairman Reince Priebus both told Trump he could not afford to equivocate. Just give a simple, direct answer, they said: "Yes, I'm going to accept it." But Trump was Trump. They never knew what he would say.

He saw the signs of rigging wherever he looked. Saw them in Iowa and Colorado, when he lost Republican contests to Ted Cruz. Saw them in Clinton's win over Sanders in the primaries, and in the FBI investigation of her email server and at the first debate, when he blamed his rough night on a temperamental microphone. People laughed, said he was making excuses, but then the presidential debate commission released a statement saying "there were issues regarding Donald Trump's audio." So there. At the second debate he said it was three-on-one, him against Clinton and the two moderators, which of course fit his larger narrative of a battle against both Crooked Hillary and her friends in the Crooked Media.

On October 7, WikiLeaks began releasing hacked emails from the private account of Clinton's campaign chairman, John Podesta. The Clinton campaign and intelligence officials blamed the Russian government for the hack, but Trump seized on the emails as more evidence that everything was rigged. Many were interesting merely for the Democrat-on-Democrat insults they contained, or for Podesta's advice on making creamy risotto, but some contained real substance. In one email to Podesta, Clinton said ISIS was receiving clandestine support from the Saudi Arabian government—the same government that had given between $10 million and $25 million to the Clinton Foundation. Another email chain showed Clinton aides debating whether lobbyists for foreign companies and governments should be allowed to bundle for the campaign. "Take the money!!" her communications director, Jennifer Palmieri, wrote. (They did.) Trump said the media should cover the WikiLeaks story much more and his female accusers much less, but he wasn't surprised, because, as he put it, "their agenda is to elect Crooked Hillary Clinton at any cost—at any price—no matter how many lives they destroy."

But going into the third debate in Las Vegas on October 19, the notion of media bias came from the other side. For the first time ever in a general election, the conservative-leaning Fox News would supply the moderator. Although Chris Wallace had a reputation for objectivity, some of Clinton's allies were skeptical—especially since Wallace's former boss, the recently departed Fox News chairman Roger Ailes, had been helping Trump with debate preparation.

"We hope that he takes a balanced approach," a Clinton aide said of Wallace that night, "but we will definitely be closely watching."

"Secretary Clinton," Wallace said about twenty minutes in, "I want to clear up your position on this issue, because in a speech you gave to a Brazilian bank, for which you were paid $225,000, we've learned from the WikiLeaks, that you said this, and I want to quote: 'My dream is a hemispheric common market with open trade and open borders.' So that's the question—"

"Thank you," Trump said.

Wallace chuckled. "That's the question. Please, quiet, everybody. Is that your dream, open borders?"

After saying she'd been talking about a cross-border energy system, Clinton quickly pivoted to complain about WikiLeaks and the Russian government. Trump called her on the evasion. Until then he was giving his best and most disciplined performance. But she had mentioned Russian President Vladimir Putin, a sore subject for Trump, and Trump couldn't let it go.

TRUMP: He has no respect for her. He has no respect for our president. And I'll tell you what: We're in very serious trouble, because we have a country with tremendous numbers of nuclear warheads—1,800, by the way—where they expanded and we didn't, 1,800 nuclear warheads. And she's playing chicken. Look, Putin—

WALLACE: Wait, but—

TRUMP: —from everything I see, has no respect for this person.

CLINTON: Well, that's because he'd rather have a puppet as president of the United States.

TRUMP: No puppet. No puppet.

CLINTON: And it's pretty clear—

TRUMP: You're the puppet!

CLINTON: It's pretty clear you won't admit—

TRUMP: No, you're the puppet.

If the playing field was tilted in Clinton's favor, Clinton herself had done the tilting—with twice-daily prep sessions, decades of policy study and enough political combat to make her almost impervious to personal attacks. The Vast Right-Wing Conspiracy had prepared her well. Here was the most basic asymmetry of all three debates: Trump could not provoke Clinton, but Clinton could and did provoke Trump. She did it strategically, methodically, relentlessly. He tried to control himself, to resist all her bait, but the temptation was too much. He was so angry by the end of the night that an unmemorable insult during Clinton's answer about Social Security provoked his most memorable interruption yet:

"Such a nasty woman."

Then, as expected, Wallace asked Trump if he would accept the election results. Contravening 227 years of American protocol, Trump refused to commit.

"But sir," Wallace said, "there is a tradition in this country—in fact, one of the prides of this country is the peaceful transition of power and that no matter how hard-fought a campaign is, that at the end of the campaign that the loser concedes to the winner."

Trump was behind in the polls, and his support was slipping further. Many in both parties believed the race was already over. Trump was 70, old enough to think about his legacy. He had said it again and again: He could do whatever he wanted with women. Now, if current trends held, he would be remembered most for losing to one.

"Not saying that you're necessarily going to be the loser or the winner, but that the loser concedes to the winner and that the country comes together in part for the good of the country," Wallace said. "Are you saying you're not prepared now to commit to that principle?"

"What I'm saying is that I will tell you at the time," Trump said, shaking the political firmament once again. "I'll keep you in suspense."

✦ ✦ ✦

Clinton entered the last days of October with victory in sight. Then a government report said Obamacare premiums would rise sharply in 2017. A hacked email from WikiLeaks raised more questions about the connection between her husband's paid speeches and her decisions as secretary of state. Finally, eleven days before the election, FBI Director James Comey dropped his bombshell.

In a cryptic three-paragraph letter to congressional leaders on October 28, Comey said the bureau had learned of more emails that appeared pertinent to its investigation of Clinton's private email server. Investigators would review those emails to find out whether they contained classified information. The emails had come to light through "an unrelated case," which turned out to be the FBI's investigation of former Congressman Anthony Weiner, the estranged husband of Huma Abedin, one of Clinton's closest advisers.

What were the most important issues facing the country? Jobs, immigration, national security? Maybe. But the presidential race seemed to revolve increasingly around sex and email.

Abedin and Weiner had separated in August 2016, during his third sexting scandal, when Weiner texted a lewd photo of himself while lying next to the couple's 4-year-old son. Soon after that, the FBI opened an investigation into allegations that he had traded explicit messages with a 15-year-old girl.

Weiner's first sexting scandal forced him to resign his seat in Congress. His second might have cost him the New York mayoralty. But the third now threatened to upend the presidential race and, possibly, keep a woman from finally ascending to the most powerful job in the world.

All through the campaign, Trump's own misbehavior accrued to Clinton's benefit. She wasn't just running to become the first woman president. She was running to defeat someone she and her supporters considered a vulgar, womanizing misogynist. He said Megyn Kelly had blood coming out of her wherever. He mocked Carly Fiorina's appearance. He said Clinton "got schlonged" by Obama in 2008. He reassured the nation about the size of his penis. He disgusted Republican women, and mobilized Democratic ones. But when Trump learned of Comey's letter, he gleefully turned the spotlight back toward Clinton.

"This is bigger than Watergate," he exclaimed at a rally in New Hampshire.

Clinton's campaign manager, Robby Mook, recalled learning about the Comey letter from traveling press secretary Nick Merrill while they were on a campaign plane between New York and Cedar Rapids, Iowa. Merrill had been informed by a Los Angeles Times reporter, apparently the only person on the plane who could get a Wi-Fi signal. "He said, 'Have you seen this? The investigation was reopened.'" Mook said.

Mook and communications director Palmieri went to tell Clinton the news. Her response, he said, was striking. "There have been moments on this campaign where I am a lot in awe of her. You can see how she's ready to be president," Mook said. "The incredible steadiness and stoic manner she had—she listened to us, she took our counsel, we made a decision to get out a statement. She was confounded the way we all were. Like, why in the world would he do this this far into the election? She wanted to respond and put our point of view out there. She was steady about the whole thing. I think anyone else would have just lost their cool."

The presidential race was scrambled again. Clinton walked off the plane in Cedar Rapids. Reporters yelled questions. She waved, and kept walking.