Here is the story of thirty-eight days in early 2016 that saw the party of Lincoln and Reagan become the party of Donald Trump. He had not won anything before this stretch began, and by the end he'd won so much that he seemed almost bored with winning. There is no way to know whether anyone could have stopped him in these days—whether a better strategy by one or more opponents might have altered the course of history—but the story of those efforts is one of blunders and miscalculations, of desperate gambles that did not pay. Time and again his rivals stumbled on themselves and each other while Trump ran on, untouched. "Hostility works for some people; it doesn't work for everyone," he said March 8, acknowledging the strange asymmetry that allowed him to say what others could not say, in a tone others could not use, while turning a victory speech into an infomercial for the water and wine that bore his name.

In fairness to the last three men who stood between Trump and the nomination, these thirty-eight days seemed to widen the very contours of reality. They did not know a modern American candidate could gain strength by encouraging violence. They were unprepared for an opponent who would be heralded by the white-nationalist fringe. They were unaware that a Republican could win a landslide victory in South Carolina the day after telling a century-old fictional story about an American general executing forty-nine Muslim terror suspects with bullets dipped in the blood of pigs.

Unprecedented 2016

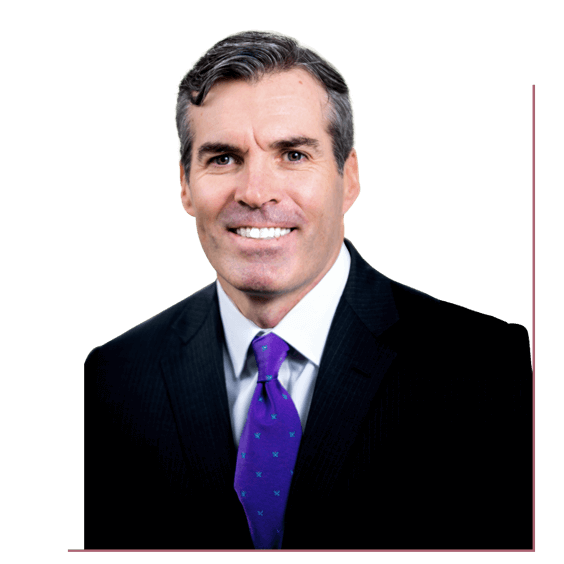

Kevin

Madden

Too much to chance

But if the Grand Old Party crossed a cosmic boundary somewhere between early February and the Ides of March, it had spent many years drifting toward the line. The party had survived for 161 years. It had produced eighteen presidents. And by 2015, it was not quite sure what it wanted to be. Its growing faction of low-income voters had few common interests with its corporate financiers, who were battling the social conservatives while also fighting the populists. If this was the party of struggling white people, it had chosen an awkward standard-bearer in Mitt Romney the last time around: a man who said corporations were people, casually mentioned that his wife drove a couple of Cadillacs, and railed against the 47 percent of low-income Americans who paid no taxes even as he lowered his own taxes by parking millions in the Cayman Islands.

Trump never pretended to be Joe Six-Pack. That would have been implausible, and a little too ordinary. Instead he won over working-class Republicans by playing the master of men like Romney—by playing a golden colossus who would gladly strike down all that displeased the "real" Americans. Let the market govern big corporations? No. The golden colossus would bend corporations to the people's will. Punish Ford and Carrier for outsourcing American jobs. Punch China in the face. And if all those other Republicans were really on your side, why did they go around asking billionaires for money? Why did Jeb Bush, Marco Rubio and Ted Cruz all go hat in hand to the industrialists who planned to spend nearly $900 million on the upcoming election?

On the weekend of the Koch Brothers' famous retreat in August 2015, Trump taunted them on Twitter: "I wish good luck to all of the Republican candidates that traveled to California to beg for money etc. from the Koch Brothers. Puppets?"

Given Trump's disruptive power, only a superlative candidate could have beaten him. On February 6, as the decisive thirty-eight-day stretch began, many Republicans thought Rubio could be that candidate. He routinely beat Hillary Clinton in head-to-head polling. He'd finished only a point behind Trump in Iowa, and that week another candidate's tracking poll showed him almost neck and neck with Trump in New Hampshire. Five months younger than Cruz at age 44, Rubio was the youngest candidate in the race and perhaps the most charismatic, with a personal story about hard work and American gratitude that played well almost everywhere. Although he'd never led in the polls, he was surging at the right time.

But first he had to finish the New Hampshire campaign, which meant taking the stage at that night's debate, which meant one last showdown with his antagonist: New Jersey Gov. Chris Christie.

"If he beat out Bush, Christie and Kasich in New Hampshire, Rubio was probably going to be the nominee of the party," Matt Mowers, Christie's New Hampshire state director, said later. "You had to stop him in New Hampshire, or he wasn't going to be stopped."

Rubio would be stopped: partly by the collision that night, and partly by forces that had been gathering within the party for a long time. At one inflection point after another in February and March, these forces conspired against everyone but Trump.

✦ ✦ ✦

As Republican-on-Republican rhetorical violence escalated in early January, one of the party's best political brawlers did something unusual: He called for peace. Christie's poll numbers were falling, thanks in part to negative ads from a pro-Rubio super PAC, and his response was a somber warning.

"Do not be fooled," Christie said in a campaign ad. "Any significant division within the Republican Party leads to the same awful result: Hillary Rodham Clinton, in January of 2017, taking the oath of office as president of the United States. This country cannot afford that outcome. And thus, we Republicans have a duty—I believe, a profound moral duty—to work together."

This is how seriously Christie took his profound moral duty: He went on the radio January 7 and said that if Rubio ran against Clinton, she would "pat him on the head and then cut his heart out."

As it turned out, Christie would do that job himself—with help from the other Republican candidates. One Republican operative recalled being approached by Christie's staff: "The first thing they said was, ‘We're going to go after Rubio—destroy him.' "

Why did they gang up on Rubio instead of on Trump? On someone who generally shared their values instead of someone who didn't? One school of thought says the whole thing was Rubio's fault. It says he never should have been in the race. In the Republican Party, candidates knew how to wait their turn. And it was not Rubio's turn.

But Rubio would not wait. Even though his list of accomplishments was short. Even though he was the third-most popular Republican presidential candidate in his own state. Even though his destruction of Bush called to mind a Burmese python invading the Everglades: Maybe he swallows the alligator, but both of them perish in the fight.

"In hindsight," said Al Cardenas, former chair of the Florida Republican Party, "Marco's entry into this race was predictably fatal for both he and Jeb."

Another theory says it was Bush's fault. It says he was always too weak to play the favorite. It says the donors who put nearly $122 million in his super PAC should have used that money to kindle a bonfire, because at least that way it couldn't have done the work of Donald Trump. It wouldn't have clogged Facebook feeds in Iowa with a video mocking Rubio's boots, filled New Hampshire mailboxes with nasty literature about Ohio Gov. John Kasich or bombarded voters in South Carolina with costly, three-dimensional mailers that turned Rubio into a weather vane blowing in the wind.

Rubio made plenty of his own mistakes. Many of the things Christie did right—taking scores of questions at his town halls, staying afterward until the last hand was shaken, texting local politicians to remind them he cared—were things Rubio neglected. He showed up late and left early. His wall of handlers made him inaccessible. One Republican leader in New Hampshire wanted Rubio to sign a card for a girl who’d lost her home in a fire. He gave it to someone on Rubio’s staff and never saw it again.

A CNN/WMUR poll released four days before the New Hampshire primary showed Rubio firmly in second place, behind Trump, with 18 percent. Christie was tied for sixth place, with just 4 percent. That made him an especially dangerous creature: the kind with very little to lose.

Besides that, he and Trump had been friends for years. Trump told Christie in 2015 that he didn't expect to make it past October—at which point he would endorse Christie, according to a Christie adviser who asked not to be named in order to speak about behind-the-scenes maneuvers. "I think they always had an understanding that the first one out would probably endorse the other," the adviser said.

Rubio's disaster during the debate at St. Anselm College in New Hampshire began when he pivoted from a question about his own experience to a talking point about another first-term senator who had run for president: "And let's dispel once and for all with this fiction that Barack Obama doesn't know what he's doing. He knows exactly what he's doing. Barack Obama is undertaking a systematic effort to change this country, to make America more like the rest of the world."

A moment later, Rubio repeated himself, almost word for word. "Let's dispel with this fiction that Barack Obama doesn't know what he's doing. He knows exactly what he's doing."

Christie pounced. "I want the people at home to think about this," he said. "That's what Washington, D.C., does. The drive-by shot at the beginning with incorrect and incomplete information and then the memorized twenty-five-second speech that is exactly what his advisers gave him."

The Christie loyalists cheered. No one had to check the record. Live on national television, Rubio had just supplied evidence for Christie's most persistent and damaging claim. Christie turned to look at Rubio. "When you're president of the United States," he said, "when you're a governor of a state, the memorized thirty-second speech where you talk about how great America is at the end of it doesn't solve one problem for one person."

It got worse from there. In short order, Rubio repeated himself yet again. In a nearby holding room, his aides watched in horror. As one adviser recalled, "He said it once. He said it twice. And then the third time, everybody was like, ‘My God, he said it a third time!'"

But Rubio wasn't done. When he repeated the Obama line for a fourth time, Christie delivered the final blow: "It gets very unruly when he gets off his talking points."

When Rubio walked into the holding room after the debate, he didn't know the extent of the damage. According to a campaign official who was there, he tentatively asked his staff: "How was that?"

Christie had been out of contention for weeks. His attack on Rubio that night would not help him win New Hampshire. But it did help his old friend from across the Hudson River, the man he would endorse in twenty days.

During the first commercial break, Trump grabbed Christie's arm

"Wow," he said, according to a source familiar with the exchange. "That was tremendous."

✦ ✦ ✦

The Hillary Nutcracker, which retails on Amazon for $30, is a crude figurine of Hillary Clinton that does, in fact, crack nuts. This product appeals to a certain kind of Republican, and occasionally turns up at campaign events. Rubio autographed one at his Super Bowl party less than twenty-four hours after his calamitous debate. The nutcracker also appeared at a popular lunch spot in Manchester called the Puritan Backroom. Its bearer was Glenn Fiscus, age 80, who had already gotten the box signed by Christie, Carly Fiorina and three-time presidential candidate Pat Buchanan. Now, hoping for one more autograph, Fiscus handed the box to John Kasich.

"No thanks," Kasich said, handing it back. "Give me a piece of paper. I'll write you a note."

This was the ground Kasich claimed during the primaries: that of the rare Republican who gave Democrats their dignity. He tried to stay positive even as his opponents went negative. He had been known as brusque and short-tempered in Washington and Columbus, but for the most part he kept that side of himself under wraps during his presidential run.

Kasich held more than 100 town halls in New Hampshire, rarely mentioning his opponents, often sounding more like a therapist than a presidential candidate. Yes, he was a Christian, but he said little about religious liberty or the Ten Commandments. He preferred to talk about loving your neighbor, visiting the elderly, giving people hugs. He gave a lot of hugs at those town halls, many after hearing stories of grief, and he gave one more at Clemson University two days before the South Carolina primary.

"Over a year ago, a man who was like my second dad, he killed himself," said Brett Duncan Smith, a young man in dark-rimmed glasses who had driven up from the University of Georgia. "And then a few months later, my parents got a divorce. And then a few months later, my dad lost his job. But—and I was in a really dark place for a long time. I was pretty depressed. But I found hope, and I found it in the Lord, and in my friends, and now I've found it in my presidential candidate that I support. And I'd really appreciate one of those hugs you've been talkin' about."

The image of Kasich embracing Smith was a glimmer of beauty in a mud-soaked brawl, a moment that might have changed something. But this would have required a Republican primary electorate that did not exist in 2016. Maybe it was there in the Reagan era, or the time of George H.W. Bush, but it disappeared in the years thereafter. There was no single reason. The party's devaluation of expertise and civility was gradual and relentless, like the ocean carving away the shore.

Here was George W. Bush, who expressed pride in his own academic mediocrity. Here was John McCain, whose choice of running mate claimed to read "all" the newspapers and magazines but could not name a single one. Here was that running mate, Alaska Gov. Sarah Palin, whose false alarm about government death panels helped normalize the wild conspiracy theories that would later emanate from Trump. Here was Senate Republican Leader Mitch McConnell, proclaiming in 2010 that his top goal was to ensure that Barack Obama was a one-term president.

How did Kasich become estranged from his own party? He disagreed with Democrats on most issues, but he did not hate the Democrats or the intellectual elite. To the contrary: He boasted that, as chair of the House Budget Committee, he helped Bill Clinton balance the federal budget. He accepted Obama's expansion of Medicaid in Ohio. Kasich spent much of his campaign stuck in an unpleasant paradox. He appealed to independents and even some Democrats who could not help him win, and turned off Republicans who could.

Kasich's surprising second-place finish in New Hampshire required a specific confluence of events: the Bridgegate scandal that Christie wore like a millstone, the ream of political obituaries that Bush could not prove wrong and the Ambush at St. Anselm, after which Rubio's voters defected to Kasich en masse. Even then he won only 15.8 percent of the vote, nearly 20 points behind Trump.

In 2016, Republican primary voters did not want a Republican who made nice with the Democrats. They preferred a man who glibly told stories of Muslim prisoners and blood-covered bullets.

✦ ✦ ✦

To win South Carolina and become the front-runner again, Ted Cruz had one task: Carry his core demographic. This group had given him victory in Iowa. It was too small to help him much in New Hampshire. But South Carolina appeared to be his friendliest territory yet. Nearly three-quarters of the state's Republican primary voters called themselves born-again or evangelical Christians.

On the surface, it seemed like a simple choice. Here they had a conservative Christian from a Southern state with the endorsement of James Dobson, a legendary figure on the Christian right who told people of faith that it was "time for us to rally around Sen. Ted Cruz." Who would they be rallying to defeat? A foul-mouthed New Yorker who recently said, "I could stand in the middle of Fifth Avenue and shoot somebody and I wouldn't lose voters."

Trump's astonishing victory among South Carolina evangelicals did not just foreshadow the end of Cruz's campaign. It raised serious questions about the political vitality of the Christian right. And it helped ensure that millions of the faithful would either stay home in November or choose between a Democrat and a man so confused by Christian ritual that in Iowa he mistook a communion plate for an offering plate.

Why did these voters reject a candidate who spent his whole campaign claiming to be their champion? David Woodard, a former Republican operative who teaches political science at Clemson University, said many of them looked at Cruz and reached the following conclusion:

"Well, he certainly didn't win me over by his Christian behavior."

The Ben Carson incident in Iowa raised ethical questions about the Cruz campaign. The South Carolina primary raised more. A fake Facebook page claimed erroneously that U.S. Rep. Trey Gowdy had switched his endorsement from Rubio to Cruz. An unsettling flier from the Cruz campaign morphed the faces of Rubio and Obama.

Cruz's campaign manager, Jeff Roe, said in an interview that Cruz's tactics were fairly tame compared to some previous South Carolina primaries. (He was right about that.) He rejected the notion that Cruz ran an unethical campaign and blamed Rubio, Carson and Trump for creating that narrative. "And it was successful" in South Carolina, he said. "But it has no bearing in reality."

On February 22, two days after finishing behind Trump and Rubio in South Carolina, Cruz fired his chief spokesman, Rick Tyler, for spreading a news item that falsely accused Rubio of disparaging the Bible. "I have made clear in this campaign that we will conduct this campaign with the very highest standards of integrity," Cruz said. "That has been how we've conducted it from Day One."

If Cruz really meant this, it is not clear why he hired Tyler in the first place. In a previous campaign, for Missouri Senate candidate Todd Akin, Tyler said of Akin's opponent, "If Claire McCaskill were a dog, she'd be a ‘Bullshitsu.'" Was Tyler caught violating the standards of the Cruz campaign, or upholding them? Either way, it cost him his job.

Why did so many evangelicals vote for Trump? He appealed to their patriotism, their frustration with globalism and political correctness, their longing for the way things used to be. One line of reasoning came from Sen. Jeff Sessions of Alabama. A Republican operative says Sessions told him, "You don't get it—we have to do something. We're losing America. Our country is in peril. He's the only person who can bring about radical change. Sometimes God uses ungodly people to do his will."

✦ ✦ ✦

After his disastrous debate, Rubio had another kind of defining moment. It was like opening a door to an alternate future and catching a glimpse of the Republican Party that might have been. He stood on the stage in South Carolina, giving a thumbs-up and smiling that million-dollar smile. To his left stood Sen. Tim Scott, the first African-American since Reconstruction to represent a Southern state in the Senate. Gowdy stood on Rubio's right, next to Gov. Nikki Haley, the daughter of Indian immigrants. "Take a picture of this," Haley had said of Rubio's entourage, "because the new group of conservatives that's taking over America looks like a Benetton commercial!"

Long after Rubio's campaign ended, his communications director, Alex Conant, thought of that picture: a Hispanic man, a black man, a white man, an Indian-American woman, all of them children of the Reagan Revolution, all ready to lead the party of tomorrow. "It still pops up on my Twitter feed pretty routinely," Conant said in July, "mostly from people who are bemoaning whatever Trump's latest outdated statement is, and they say, ‘To think, this is what we could have had.'"

Rubio had some momentum coming out of South Carolina. His aides expected 2,000 people at a rally outside Nashville; more than 5,000 turned out. In Nevada he beat Cruz for the second time in a row. Endorsements rolled in. The establishment coalesced behind him. But time was short. Trump had won three of the first four states; Rubio had won zero. "And so," Conant said, "there was a real expectation amongst our supporters, our donors, the media, that Marco would confront Trump at the Houston debate. We were ready to do it, but I also don't think there was any other choice."

Rubio seemed to enjoy lampooning Trump. "If he hadn't inherited $200 million," he said in Houston, "you know where Donald Trump would be right now? Selling watches in Manhattan."

But he moved in a perilous direction. The more the race resembled entertainment, the more it favored the professional entertainer. Was Trump an unserious candidate? It was easier to make this case while looking the part of a serious candidate. Rubio knew that. He had tried that. And it simply didn't work. Fifteen days later, comprehending both the magnitude of his errors and the imminent end of his campaign, he explained the conundrum of running against Trump. He'd been giving serious policy speeches for months, he said, and the media paid little attention.

"And the minute that I mention anything personal about Donald Trump, every network cut in live to my speeches, hoping I would say more of it."

Now Rubio tried to keep the spotlight on himself by offending Trump in new and inventive ways. "You wanna have a little fun?" Rubio asked his fans in Dallas. They cheered. He pulled a smartphone from his pocket. "All right. What does Donald Trump do when things go wrong? He takes to Twitter. I have him right here. Let's read some. You'll have fun."

Rubio's grin registered somewhere between Hollywood red carpet and boy with hand in cookie jar. "He called me Mr. Meltdown," Rubio said during a riff that lasted more than ten minutes. "Let me tell you something: Last night during one of the breaks, two of the breaks, he went backstage. He was having a meltdown. First he had this little makeup thing, applying like makeup around his mustache because he had one of those sweat mustaches. Then he asked for a full-length mirror. I don't know why, because the podium goes up to here, but he wanted a full-length mirror. Maybe to make sure his pants weren't wet, I don't know."

Rubio was the talk of the nation. The networks had given Trump frequent coverage, helping him drown out the other candidates. Now he had an apprentice. In Georgia on February 27, Rubio said Trump should sue the person who gave him the nation's worst spray tan. In Virginia a day later, he said Trump would make America orange. Then he jumped all the way into the gutter. "He's always calling me Little Marco," Rubio said. "…He's taller than me—he's like six-two. Which is why I don't understand why his hands are the size of someone who's five-two." He held up his right hand, curling the fingers to make them short. "Have you seen his hands? They're like this. And you know what they say about men with small hands—"

The audience gasped in amusement and surprise, with a dash of what might have been horror.

"—you can't trust 'em," said the man who wished to lead the free world.

Two days before the pivotal contests of the first Super Tuesday, the Republicans stood in a startling place. A field of seventeen candidates had been narrowed to five. And combined, the four who weren't named Trump had less national support in the latest CNN/ORC poll than Trump, who on CNN's "State of the Union" with Jake Tapper that morning refused to disavow former Ku Klux Klan grand wizard David Duke or the white supremacists who evidently found his message inspiring

Unprecedented 2016

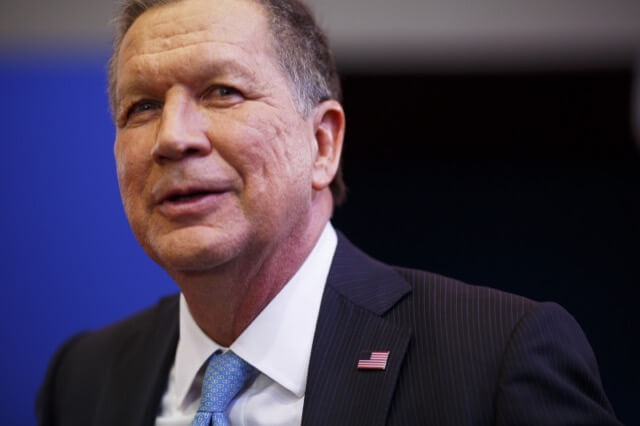

Maeve

Reston

A story of forgiveness

Democrats watched in fascination. They couldn't have scripted the Republican primaries better if they had tried. According to Clinton ally (and former nemesis) David Brock, founder of the pro-Clinton research organization Correct the Record, only four Republican candidates ever worried them: Bush, Christie, Wisconsin Gov. Scott Walker and Rubio. Whenever Democratic researchers found dirt on those four, they publicized it right away. Now three of those candidates were gone, and the fourth was rapidly fading. The Democrats had built a vast opposition file on Trump as well, but they saved that material for later. They wanted him to win the primaries, Brock said, because they were pretty sure they could destroy him in November.

"We got the race we wanted," Brock said, "for better or worse."

Trump won seven states on Super Tuesday. Cruz won three, just enough to stay viable. Rubio won only Minnesota. Cruz argued that he could beat Trump one-on-one if Rubio would only get out of the race. But Rubio stayed in.

In Cruzworld, another idea surfaced. Maybe they could persuade Rubio to join forces against Trump. Cruz was serious enough about the alliance that he authorized Sen. Mike Lee of Utah to go to Miami ahead of the CNN debate there March 10 to help work out a deal.

"I think the two of them as running mates would have been unstoppable," Lee told CNN later. "They would have united the party."

Lee bought a ticket to Miami at his own expense and booked a hotel suite where he hoped Cruz and Rubio would meet. According to two sources familiar with the talks, Rubio initially seemed open to the idea. But just as Lee was about to board his flight, Rubio had a change of heart. "I don't think I can do this. I don't think I can back out and not be a presidential candidate prior to the primary in Florida," Rubio told Lee, according to one of the sources. Lee flew to Miami anyway, but the meeting never took place.

Instead of meeting with Cruz, Rubio reached out to his onetime mentor, Jeb Bush, to ask for an endorsement. Bush still was revered in Florida Republican circles, and his stamp of approval could have helped rally the party to Rubio's side before the must-win Florida primary.

But the governor had not forgotten his protégé's disloyalty, his impatient decision to enter the race. Bush withheld his endorsement, leaving Rubio to fight Trump on his own.

✦ ✦ ✦

On the morning of March 11, four days before the Florida primary, Corey Lewandowski stood in a ballroom at Trump's Mar-a-Lago Club in Palm Beach, holding a Monster energy drink. Trump's campaign manager had a volatile relationship with the press. One moment he could joke around; the next he might threaten to have a reporter blacklisted. Now he made a joking threat with a sinister undertone.

"You ask tough questions," he said, "you get roughed up."

The reference seemed obvious, and astonishing: Earlier that week, a Breitbart reporter named Michelle Fields alleged that Lewandowski had grabbed and bruised her arm when she tried to ask Trump a question. (Prosecutors would decline to file any charges, citing their inability to prove a crime.) In a few minutes, Ben Carson would stroll inside and offer his endorsement of Trump, the man who recently compared him to a pedophile. In a few hours, former First Lady Nancy Reagan would be interred on a misty hillside in California after her death at age 94. This day of mourning would also be remembered for its violence, which could now be called a recurring theme for the Trump campaign.

At the front of the ballroom, still waiting for Trump, Lewandowski continued his spontaneous news conference.

"What about the candidate himself?" a reporter asked. "You know, ‘I feel like punching the guy in the face,' he said at one rally. That doesn't help, does it?"

"Well, look," Lewandowski said, "I think Mr. Trump's people are very, very passionate. And they're angry, because of the way this country has been taken advantage of, from so many other countries. And so that's the frustration level that I think a lot of people in this country feel, and people express it in different ways."

Most Trump supporters were white, and they often expressed that anger against African-Americans. This happened at a Trump rally in Kentucky in March, when a white nationalist and other Trump supporters were caught on video repeatedly shoving a young black woman. It happened in Nevada in December, when officers removed an African-American protester and a Trump supporter yelled, "Light that motherfucker on fire!" It happened in North Carolina in March, when a man in a cowboy hat punched a black protester in the face and then said, "Yes, he deserved it. The next time we see him, we might have to kill him." It happened in Alabama in November, when white Trump supporters punched and kicked a black protester, after which Trump used a phrase strikingly similar to the one Lewandowski uttered at Mar-a-Lago: "Maybe he should have been roughed up."

In other words, Trump gave them permission. And sometimes more than that. In Iowa on February 1, he said, "So if you see somebody getting ready to throw a tomato, knock the crap out of 'em, would you?" The following month, as security escorted a protester out of a Michigan rally, Trump said, "Get him out." He added, "Try not to hurt him. If you do, I'll defend you in court. Don't worry about it."

On March 11, at Trump's rally in St. Louis, more than thirty people were arrested. A black man stood by an ambulance, with tissue paper in his nostrils and bloodstains on his shirt, telling someone he'd been sucker punched. Inside the Peabody Opera House, as protesters disrupted the proceedings for more than ten minutes, Trump stumbled upon a profound and unsettling truth: "Honestly, can I be honest with you?" he said. "It adds to the flavor. It really does. Makes it more exciting. I mean, isn't this better than listening to a long, boring speech?"

It is hard to run against a man who turns violence into entertainment, and entertainment into votes. His fellow Republicans had many flaws. But there is another reason they could never appeal to some voters the way Trump did: They had too much common decency. Only Trump could tell security to confiscate protesters' coats before ejecting them into a 25-degree night.

After the mayhem in St. Louis, Trump canceled a rally in Chicago, citing danger from thousands of militant protesters. Fistfights broke out in the arena. A bottle struck a police officer. Scenes of violent chaos appeared on television. And Ted Cruz held on to conventional wisdom like a man to a sinking lifeboat. Which is to say he blamed Trump.

"When you have a campaign that affirmatively encourages violence," Cruz told reporters in Illinois, "you create an environment that only encourages that sort of nasty discourse."

But Cruz misjudged the new Republican electorate. Blame Trump? Not a chance. The protesters added to the flavor. They made it more exciting. Many were college students; many were black and Latino. They symbolized the leftist thought police Trump had been preaching against from the beginning. This is why Cruz's top aides came to see the entire Chicago incident as a strategic play by the Trump campaign—and a brilliant one at that. Trump the perpetrator became Trump the victim. The next morning he tweeted, "The organized group of people, many of them thugs, who shut down our First Amendment rights in Chicago, have totally energized America!"

Before March 11, Cruz thought he could win Missouri and North Carolina. He lost them both, along with his best hope of overtaking Trump. Whatever the anti-Trump demonstrators meant to do, Cruz's aides believe they delivered both states to the man they despised. Who was soul-searching after that? Not the protesters. They believed they had won by closing down Trump's rally. Not the Trump voters. This was their party now.

Barely 200 people turned out for Rubio's election-night bash in his hometown, Miami, in the only county of Florida's sixty-seven he did not lose to Trump. Some left before Rubio arrived. A few more stayed to watch him drop out of the race and disappear behind a black curtain. Some went past the curtain, looking for him, imagining some kind of after-party. Instead they found an aide wiping tears from her eyes and a security guard nudging them toward the door.

"The candidate is gone," he said.