There was a woman who loved a country that had always been governed by men. She pledged allegiance to its flag and stood, hand over heart, during its national anthem. She often proclaimed its greatness—insisted it had never stopped being great—even as her opponent insisted it was in sharp decline. The voters had never seen such a contrast. Soon they would choose between this woman and a man who called women dogs, judged their bodies, insulted their faces, hinted crassly about their personal hygiene, and hoped to end her political career even as he became the nation's forty-fifth consecutive male president.

It was just before 9 p.m. on Thursday, July 28. In two hours Hillary Clinton would become the first American woman to accept a major party's presidential nomination. Tens of millions watched on television, including Elizabeth MacNaughton, age 98, a psychologist born before women won the right to vote. Too frail to travel from Houston to the Democratic convention in Philadelphia, she promised her daughter she would stay alive long enough to vote at least one more time.

Thousands waited inside the Wells Fargo Center, including Kim Frederick, a Democratic activist who had seen a 2014 Time magazine cover that depicted Clinton on the verge of crushing a man with her high heel. Frederick was so incensed by the sexist media coverage that she founded a group called HRC Super Volunteers. Frederick had traveled from Texas to Iowa to Minnesota, losing touch with her best friends, spending most of her free time to help Clinton win the nomination. Now, as she sat with the Texas delegation, she felt as if she hadn't slept in two years.

Hundreds waited in the corridors of the packed arena, held at bay by the ushers, hoping seats would open up. Ruth Ellis, a 54-year-old teacher trainer, had driven from California in an RV with her husband and a 19-year-old son with Down syndrome. She stood outside Section 210, near the lighted sign for Chickie's and Pete's Crab House and Sports Bar. Ahead of her, after ninety minutes in a line that barely moved, another woman decided to cut her losses.

"Does anybody want my sign?" she asked.

"Are you giving up?" Ellis responded. "No, no, no, no. I'm not letting you give up."

By the time Hillary Clinton was born in 1947, Americans had already invented the airplane, the atom-smasher and the general-purpose computer. In her lifetime they would put a man on the moon and a woman in space. But another thing did not happen, and its absence seemed to call for an explanation. As dozens of other nations elected their first female leaders, the United States did not even come close. Clinton was 12when Sirimavo Bandaranaike became prime minister of Ceylon, 18 when Indira Gandhi became prime minister of India, 21 when Golda Meir became prime minister of Israel. In 1972, when Congresswoman Shirley Chisholm ran for the Democratic nomination for president, she received about 430,000 votes and finished behind six men.

"When I ran for the Congress, when I ran for president, I met more discrimination as a woman than for being black," Chisholm said later. "Men are men."

Thirty-six years would pass before another woman received that many votes again.

"Oh, come on," Ruth Ellis said as a man left the line outside Section 210. "Don't give up. Hillary didn't give up!"

In October 1984, the same month Indira Gandhi was assassinated, the first American woman to run on a major-party ticket took part in a vice-presidential debate.

VICE PRESIDENT GEORGE H.W. BUSH:

Let me help you with the difference, Ms. Ferraro, between Iran and the embassy in Lebanon.CONGRESSWOMAN GERALDINE FERRARO:

Let me first of all say that I almost resent, Vice President Bush, your patronizing attitude that you have to teach me about foreign policy.After the debate, Bush remarked that he had "kicked a little ass."

In 1986, Corazon Aquino of the Philippines became the first female president in Asia. In 1988, Benazir Bhutto became prime minister of Pakistan. The following summer, Arkansas First Lady Hillary Clinton and her 9-year-old daughter, Chelsea, were vacationing in London when they noticed a crowd outside the Ritz hotel. They watched Bhutto get out of her limousine and walk into the lobby. As Clinton would later write, "Bhutto was the only celebrity I had ever stood behind a rope line to see."

A few months later, 11-year-old Kim Frederick was riding in the car when she heard a radio news report about Clayton Williams, the man running for governor of Texas against State Treasurer Ann Richards. With reporters present, Williams had recently made a joke about rape: "If it's inevitable, just relax and enjoy it." The following year, 1991, Frederick watched the all-male Senate Judiciary Committee aggressively question Anita Hill about her allegations that Clarence Thomas, who was nominated to sit on the Supreme Court, had sexually harassed her. The year after that, when Bill Clinton was running for president, Frederick read Hillary Clinton's defiant quote in defense of her law career—"I suppose I could have stayed home, baked cookies and had teas"—and watched her withstand the ensuing attacks. A teenage girl was becoming a feminist.

Hope dwindled in the corridor outside Section 210. The line barely moved. Ellis strained to see beyond the curtain. She asked the usher to move aside, to make a sight line, but the usher refused.

"Seriously," Ellis said with exasperation, "this is once in a lifetime."

Or once in 227 years.

A sound came from the arena, louder and louder, a battle cry that conjured visions of a Trump rally. But these were Democrats, chanting with all their hearts:

U-S-A! U-S-A! U-S-A!

✦ ✦ ✦

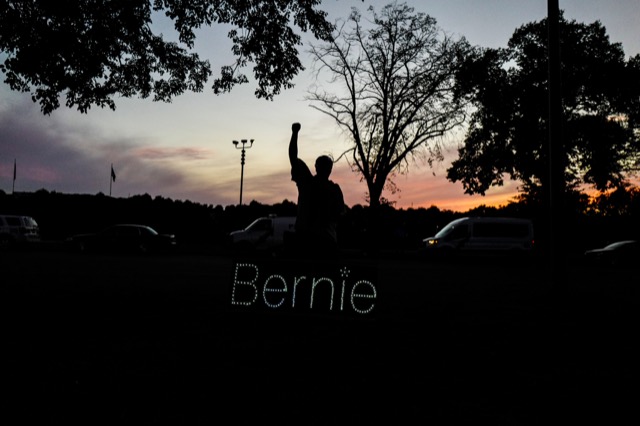

Before the Democrats could wrestle Trump for the flag—before they could make the case to the nation that they were the real patriots—they had to reckon with their own civil war. Three days before the convention, WikiLeaks published a trove of stolen emails that appeared to show Democratic National Committee officials plotting against Bernie Sanders during the primaries. In the most flagrant example, chief financial officer Brad Marshall shared an idea with chief executive officer Amy Dacey a few days before Democrats voted in Kentucky and West Virginia:

"It might may (sic) no difference, but for KY and WVA can we get someone to ask his belief. Does he believe in a God. He had skated on saying he has a Jewish heritage. I think I read he is an atheist. This could make several points difference with my peeps. My Southern Baptist peeps would draw a big difference between a Jew and an atheist."

Dacey replied:

"AMEN"

The DNC did not follow Marshall's suggestion. In an interview later with CNN, Dacey said, "I got an email and I was trying to be dismissive and shut down the conversation. I chose an awkward word. There was no way we were ever going to pursue that."

But the damage was done. When Clinton announced Virginia Sen, Tim Kaine as her running mate that Friday night, July 22, #DNCLeaks was the leading hashtag on Twitter. Sanders and his revolutionaries already believed the party was biased against them. Now they had fresh evidence. On Sunday morning, his campaign manager, Jeff Weaver, appeared on CNN and said, "There's obviously a problem here. Someone should resign. It should be—Debbie Wasserman Schultz should resign."

Democrats would later complain about how Wasserman Schultz, a congresswoman from Florida, conducted herself that week—about her initial resistance to resigning as chairwoman, about the way she hung around Philadelphia, looking for hugs and sympathy. Between the furious Berniecrats and the donors who were embarrassed by some of the emails and worried their personal information had been breached, it was hard to find Democrats willing to defend her. She was loyal to Clinton. Her five years as chairwoman had led to this moment. She wanted to gavel in the first major-party convention ever to nominate a woman for president. But that was not to be.

The day before the convention started, Clinton's campaign manager, Robby Mook, and her liaison to the DNC, Charlie Baker, met with Wasserman Schultz in her Philadelphia hotel suite. Also there was Hilary Rosen, a friend of the Florida congresswoman's and a Clinton surrogate. According to Rosen, Mook and Baker told Wasserman Schultz: "'The Bernie people say this is going to be bad, that they're going to protest. We don't really want a protest. But Hillary's your friend and we'll support you whatever you decide.'" Wasserman Schultz asked Mook and Baker to give her a few minutes to think it over.

While the Clinton emissaries waited in the hall, Wasserman Schultz talked with her chief of staff, Tracie Pough, and Rosen. The embattled DNC chair knew what she had to do, and she would do it. But only after opening the convention. She and Rosen contacted the White House to let them know she'd be resigning at the end of the week. Then Rosen called Donna Brazile, the DNC's vice chair. "I said, 'You better get over here. You're about to be the chair of the DNC.'" Rosen recalled. "She's like, 'What the fuck?'"

But things went south the next morning, at a breakfast for the Florida delegation. Sanders supporters started yelling at Wasserman Schultz and her supporters started yelling back, and the room got very loud. According to Rosen, "Debbie said, 'Look, this is not worth it—to have us be booed at the opening of the convention. So I'm not going to open the convention. I've already resigned. Forget it.'"

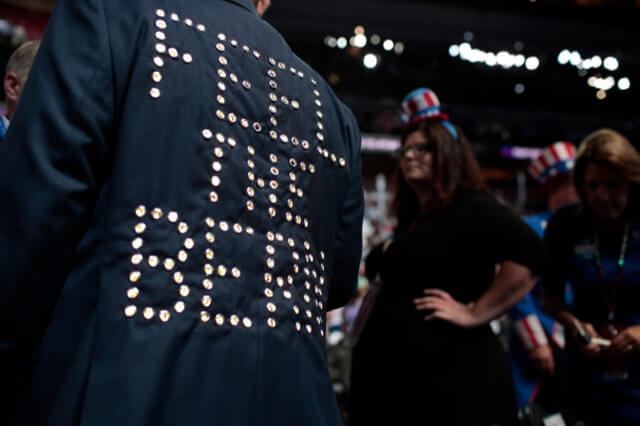

No one starts a revolution in the hope of tamping it down. But this is what Sanders did. His aides worked with Clinton's on a plan to prevent disruptions, and convention speakers were coached to ignore protests on the floor and focus on the TV audience. Sanders himself sent out a text message to the delegates. "I ask you as a personal courtesy to me to not engage in any kind of protest on the floor," he wrote. "It's of utmost importance you explain this to your delegations." When his campaign manager, Weaver, ran across the new interim DNC chairwoman, Brazile, he pledged to help her however he could. "I love you," they both said, embracing.

In his speech on the convention's first night, Sanders went on for a while about himself and his revolution. And then the newly minted Democrat did his part to repair the Democratic Party. He said, "Hillary Clinton must become the next president of the United States."

When his own supporters booed him at a delegate breakfast the next morning, Sanders responded with his own version of an appeal to fear that Clinton had been using for months. "It is easy to boo," he said, "but it is harder to look your kids in the face if we are living under a Trump presidency."

✦ ✦ ✦

The convention speakers—younger, more diverse, and collectively about a thousand times more famous than their Republican counterparts—had one main objective: repair the damage that Trump and the Republicans had done to Hillary Clinton's reputation. And, of course, join together in a star-studded rendition of "Fight Song," during which the pop singer Ester Dean incorporated Clinton's book titles into a set of rap lyrics. They did know how to have a good time.

"In the spring of 1971 I met a girl," Bill Clinton said on the second night, trying to personalize his wife's story while also trumpeting her decades-long work on such issues as equality, education, child welfare, health care and aid to the 9/11 first responders.

"Now," he said, "how does this square? How did this square with the things that you heard at the Republican convention? What's the difference in what I told you and what they said? How do you square it? You can't. One is real; the other is made up. You just have to decide. You just have to decide which is which, my fellow Americans."

Long ago, the Republicans had decided they would rule the territory of flags and fireworks and parades and police officers and banging the drum for America. And after they noticed something unusual about the first night of the convention, Trump went on Twitter to question the Democrats' patriotism once again: "Not one American flag on the massive stage at the Democratic National Convention until people started complaining-then a small one," he wrote. "Pathetic."

But in 2016 the Republicans were losing their grip on patriotism, thanks in part to the nominee who had just called on Russia to find Clinton's missing emails. And as the Democrats methodically built an argument for Clinton as the most qualified candidate ever to run for president, some conservatives also thought the Democrats looked more like Republicans than the Republicans did. As National Review editor Rich Lowry tweeted, "American exceptionalism and greatness, shining city on hill, founding documents, etc—they're trying to take all our stuff."

Suddenly American flags were everywhere: on the stage, in the bleachers, atop the tall blue signs that said HILLARY. The Democrats held up a mirror to Trump and dared the voters to call him a patriot. "He even mocks our POWs, like John McCain," retired Rear Admiral John Hutson said on the third night of the convention. "I served in the same Navy as John McCain. I used to vote in the same party as John McCain. Donald, you're not fit to polish John McCain's boots."

Vice President Joe Biden lit up the room that night, and when he said, "It's never, never, never been a good bet to bet against America," the delegates broke into an unexpected chant. Trump didn't own those three letters, and neither did the Republicans. U-S-A! U-S-A! U-S-A! The feminist attorney Gloria Allred chanted vigorously, as did Kim Frederick, as did a man in a royal blue turban.

"And most of all," President Obama said a few minutes later, "I see Americans of every party, every background, every faith who believe that we are stronger together—black. white, Latino, Asian, Native American; young, old; gay, straight; men, women; folks with disabilities, all pledging allegiance, under the same proud flag, to this big, bold country that we love. That's what I see. That's the America I know!"

This was another kind of patriotism, broader than the kind Trump was selling. And if it felt ambivalent about the past that Trump glorified, it viewed the present and future with unabashed optimism. In the forty years before Obama's inauguration, with Republicans dominating the White House, the Democrats drew much of their vitality from protest and dissent. Now they'd been in charge for almost eight years: jump-starting the sputtering economy, killing Osama bin Laden, passing a health care plan that drastically reduced the number of uninsured Americans. If Trump wanted to bring back the nation that existed in his mind, Obama described the nation that actually was—the one that elected a black president and might soon elect a woman president, the one where more than 50 million residents spoke Spanish, the one whose white population was expected to fall below 50 percent before 2050. In this America, the headstones at Arlington National Cemetery bore all kinds of inscriptions. Some had Muslim crescents.

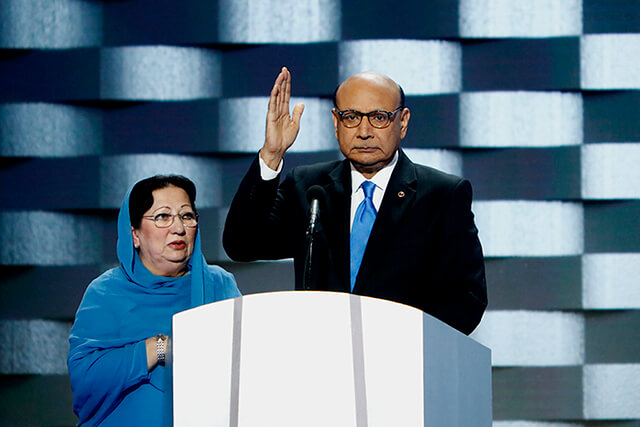

The Army captain was 27 years old on the day an orange car drove up to the gates of his base. He was a good soldier, fighting Bush's war, admiring John McCain, ordering his fellow soldiers to take cover even as he walked toward the suspicious car. That car exploded on June 8, 2004, in Baquba, Iraq, killing Captain Humayun Khan, and twelve years later his mother and father took the stage together on the fourth and final night of the Democratic National Convention. Ghazala Khan said nothing. Khizr Khan said only 357 words. He could have said less. What mattered was the physical, the indisputable, the sight of two Muslim Americans who had given their son for the country they loved.

"Hillary Clinton was right when she called my son the best of America," Khizr Khan said. "If it was up to Donald Trump, he never would have been in America."

He reached into his jacket, drew out his pocket U.S. Constitution and offered to lend it to Trump.

"You have sacrificed nothing, and no one," he said, baiting a trap that his adversary would barrel into.

✦ ✦ ✦

More than seventy modern nations had inaugurated a female head of state by the time the Democrats nominated Clinton. Given this context, one line from First Lady Michelle Obama's convention speech stood out all the more: "And because of Hillary Clinton, my daughters—and all our sons and daughters—now take for granted that a woman can be president of the United States."

This was the paradox of Clinton, a woman who had come to seem almost ordinary in her long and lonely pursuit of the extraordinary. She was the one who finally surpassed the mark set by Shirley Chisholm in 1972. She surpassed it by more than 17 million votes.

And she still lost the nomination to a man with half her accomplishments—a man who told her, with a mixture of kindness and condescension, "You're likeable enough."

There was something people said about Clinton. Men said it. Women said it. Liberals said it. Conservatives said it. Young people said it. Old people said it. They said, with slight variations:

I want a woman to be president. Just not that woman.

They gave all kinds of reasons. Not a woman who laughed the way she did. Not a woman who looked the way she did. Not a woman who yelled the way she did. Not a woman who stretched the truth the way she did. Not a Democratic woman. Not a moderate woman. Not a liberal woman. Not a hawkish woman. Not a woman who took large corporate donations, used a private email server, and mixed State Department priorities with those of the Clinton Foundation. Not a woman who would return the nation to the scandal-filled days of her husband's two terms in office. Not a woman whose rise to national prominence was inextricably linked with her choice not to leave her cheating husband. Did they judge men by the same standards? One had only to look at her husband's enduring popularity to conclude that they did not.

"You can be the most admired person in the world, until you want power, girl," Rosen said. "Then all of a sudden there's a ceiling on how willing we are to let you claim it, you girl-in-a-pantsuit who doesn't smile enough for us."

Clinton's loss to Barack Obama in 2008 left her in a strange place. She had shown that a woman could almost win her party's nomination, could almost be president. But as Michelle Obama said, it meant that more voters would take her for granted next time around. They now assumed that a woman could become president, would be before too long. Clinton received fewer votes as the winner of the 2016 primaries than she had as the loser in 2008. As if she were running for re-election to an office she had never held.

Just not that woman? She had no counterpart in American history. It was Clinton, or no woman at all. That was how Kim Frederick saw it, anyway. She was only 38, but she was convinced of this: "If Hillary Clinton can't become president, I will not see a woman president in my lifetime."

✦ ✦ ✦

Ruth Ellis had come all the way from California to see Clinton accept the nomination, but now she was stuck in the corridor outside Section 210. Maybe it's not gonna happen, she thought. Finally, at 9:33 p.m., the usher let Ellis and three friends walk past the curtain and stand in the tunnel that led to the arena.

"WOOOOO!" Ellis said. She was on the upper level, staring far down across the vast arena toward the left corner of the stage. There was Katy Perry, singing about victory, her sequined dress glittering in the spotlights. The fire marshal walked in, clearing the tunnel, sending Ellis and her friends back to the corridor. Two gave up and left the building. And then the fire marshal was gone, and Ellis and another friend went back inside. This time no one stopped them.

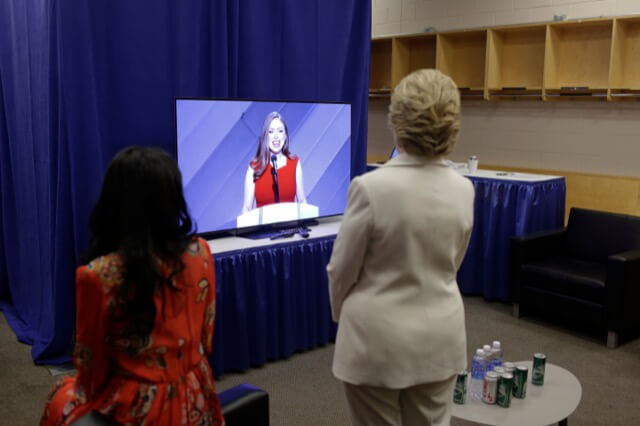

"Ladies and gentlemen," Chelsea Clinton said, "my mother, my hero and our next president. Hillary Clinton."

The wall behind the stage pivoted, and Clinton walked out through the opening. She hugged her daughter, waved to the cheering crowd. "Thank you," she kept saying, and "Oh, my gosh." She paced the stage, hand over heart, apparently overwhelmed with gratitude. The standing ovation would last more than three minutes. Kim Frederick had planned to hold it together, but no. Here came the tears. Ruth Ellis turned to her friend and screamed. For a moment she felt as if she were on stage with Clinton, as if they had done this together. Ellis could remember being 7 years old, watching Neil Armstrong's televised walk on the moon. She felt then the way she felt now: overjoyed, filled with awe, proud to be an American.