The

disappearing

front porch

Children, families caught in the crosshairs as bullets pierce sense of safety in Chicago

Before they go to kindergarten, children in Chicago learn to hit the floor at the sound of gunfire.

One child age 16 or younger is murdered in the city every week on average. This has been happening for more than a quarter century, police records show. Neither homes nor streets are safe. Those are the first and second most likely places to get murdered in Chicago since 2001.

The damage feels irreversible for those living this reality. Four families share what it's like to have their safe havens stolen, and describe their fight to take them back.

Chicago (CNN)

West Humboldt Park neighborhood

She dodged 12 bullets while sitting on her dad's lap

Gunfire erupts in the middle of the day.

Etyra Ruffin, 10, is sitting on her father's lap on her grandma's front porch. Her friend, 11-year-old Devin Henderson is playing a video game downstairs near a window.

In a split second, all hell breaks loose.

"Get down!" Etyra hears people shouting. Devin's mother, Nanette Rios, starts screaming his name. He gets down on the floor as bullets hit the porch deck, splintering the wooden base.

Nanette grabs Devin and drags him to her room as another bullet strikes the steel steps below the porch. Eytra's father, Travis, stumbles into the house and shields her from the gunfire.

She notices her dad's shirt is covered in blood. Downstairs, in the bedroom closet, Nanette anxiously waits with her son. It's the safest spot she can think of.

"Oh my God. Oh my God," Nanette repeats, waiting for the gunfire to subside.

Finally, silence.

Nanette's family is safe. She races out of her apartment and calls 911. She prays no one is dead as she runs to check on her neighbors.

She sees Travis, Etyra's father. He had been shot in the back of the head, under his arm, in his chest and his leg. Nanette grabs a face towel and covers a wound on his neck. She tells him to focus on her. Then she spots a wound in his arm and wraps it tightly.

Etyra's arm is bleeding. She is crying and in pain. But she's terrified about her dad.

"He got blood all over him," Etyra says.

I'm not going to see him again, she thinks.

This was September 1. Travis survived.

For the past 15 years, someone has been murdered on a porch every three weeks on average, according to Chicago police records. Many are shot because they find themselves innocently in the line of fire. Sometimes they are caught in the middle of drug deals or gang violence. Other times it's about who they know or hang out with.

Etyra is lucky. She dodged 12 bullets, faring with only a graze wound. She dreams of being a doctor someday and hopes being part of a grim statistic in Chicago won't hold her back.

As Etyra talks about her hopes, the reality around her drowns them. Engines turn on and off as people cross the street to buy drugs in her neighborhood. Some walk down the street screaming profanities, flicking baggies or rolling joints.

Devin seems keenly aware. He knows that throwing gang signs can get him killed, that guns are everywhere and that safety is scarce.

So he doesn't go outside.

"I feel scared in Chicago," Devin says. "All these people getting killed, I feel sad. I feel scared. I don't want to be shot."

Melrose Park, Chicago suburb

Her son was killed during 12th drive-by shooting

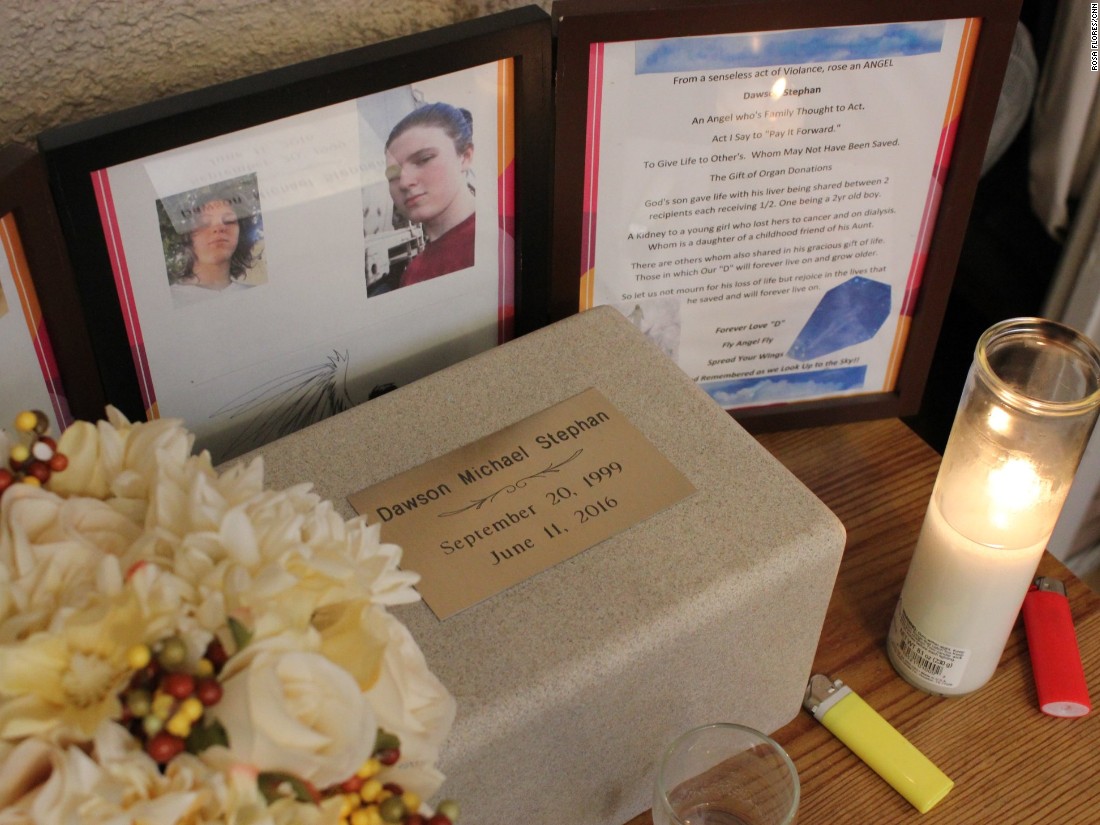

Michelle Stephan wakes up to the sound of gunfire and hears her family shrieking.

"Not Dawson, please don't say it's Dawson!" they scream.

She jumps out of bed and runs to her back deck, wearing pajamas and no shoes. Her son Dawson was outside talking with a friend before she went to sleep. He is now lying in the same spot on the deck.

It is the 12th time her house has been shot at in three years. This time her 16-year-old son was shot in the head.

Michelle bursts out crying and rushes up the steps of the deck. Her daughter-in-law calls 911. With her other son's help, she carries Dawson down the steps and toward the front gate.

"Please don't go. Please don't go, just let me know you're staying with me. Stay with me," Michelle begs Dawson as they approach her van.

Dawson's blood runs down her arms.

Police arrive as Michelle tries to close the door of her van to rush Dawson to the hospital, but officers stop her, telling her paramedics are on the way.

An ambulance rushes away with Dawson. Barefoot and in her blood-soaked pajamas she jumps in a police car and is driven to the emergency room, she says.

Dawson was on life support for six days before he was pronounced dead.

"It was very traumatic to sit there and watch him slowly die," Michelle says. "Feeling the warmth of his hands and his body and watching the coldness just leave."

Michelle keeps her blood soaked pajamas in a clear plastic bag and says she hugs them and holds them close to her heart. It's how she can feel her son hug her back. She created a memorial on the back deck where her son was sitting before getting shot. No one is allowed on the deck, only a pot of white flowers rest there to remember Dawson, she says.

"Is there such a thing as a safe place?" Michelle asks. "What kind of country is this when you can't sit on your patio?"

Police found nine shell casings at her home.

Michelle doesn't feel safe inside her house either. She points to bullet holes that cross her entire house, from the front living room window, to her kitchen cabinets in the back of the house. Bullets puncture her entertainment center, a wall, and even a door frame.

Investigators counted 34 bullet holes total. Police say they've been called to this home many times before and that it's known for gang-related activity -- an accusation Michelle adamantly denies.

Michelle hangs thick blankets over her front windows to calm her fears. She worries a shooter could aim toward a shadow inside her home.

"It's getting worse, and believe me, I used to be someone who would say it would never happen around here. It could never happen; it's such a beautiful community. And it has happened," Michelle says. "There is no safe place. As crazy as it sounds, it's true. You have to watch and be very diligent."

Murdered in their safe havens

Most murders in Chicago have occurred in homes and streets since 2001. Guns are used in 90% of the killings, according to Chicago police. The violence is not isolated to one neighborhood. Each dot shows the location of a homicide in a place considered a safe space – a home, an apartment, a front yard or porch – since 2001.

Source: Chicago police department, as of 12/1/2016

Grand Crossing neighborhood

She's a grandmother patrolling her own block

Stephanie Armas glares over the metal gate from her front porch and begins her daily morning patrol.

She observes the vibe of the street with a keen eye. Stephanie walks towards the local liquor store and back home, tracking who is coming and going. Only then she decides if her grandchildren can play outside.

It's hard to tell if it will be a calm day, or one when gangs will try to settle a score.

"If they are having some kind of disagreement on either one of the corners, I don't allow my kids to come out," Stephanie says. "I'm ready to buy everybody bullet-proof vests the way they are popping these kids."

When she sees a heavy police presence or random people casing the street on bikes, she doesn't let her children outside either, she says. Instead, she teaches them to duck and dodge bullets and stay away from windows.

"It hurts me to tell them that they can't go out to enjoy the fresh air and play in the sun," Stephanie says. "It's very disheartening to have to tell them that; but it keeps them safe."

Stephanie moved to the Grand Crossing neighborhood to avoid being on constant guard. She left the infamous Englewood neighborhood on Chicago's south side about six months ago, hoping her grandkids could play outside in a new ZIP code.

8,105 people were murdered in the last 15 years, Chicago police records show. They were most likely to take place:

- 1. On the street (3,877)

- 2. In a vehicle (978)

- 3. At an apartment (765)

- 4. In an alley (516)

- 5. In a house (447)

- 6. On a porch (246)

- 7. In a yard (164)

But, that's not what happened.

"It's terrible," Stephanie says. "It's just as bad here in this neighborhood as it is in Englewood."

The most common place for murders in Chicago, since 2001, is a city street, police records show.

Shootings happen so often, Stephanie says, people even use shooting locations as landmarks and can easily rattle them off.

It sounds something like this:

"This guy was shot here. The little girl was shot there. Remember on the next block the bullet hit this guy?" Stephanie says.

Stephanie's family hasn't fallen victim to Chicago's violence, and she wants to keep it that way.

"There is violence everywhere. You can't run from it." Stephanie says while standing on her front steps. "It's the city we live in; but you have to learn how to survive in it."

Englewood neighborhood

He traded a gun for a yoga mat to change his block

On a sidewalk in Englewood, Quentin Mables ponders how to free his childhood neighborhood from chronic violence.

The homes on either side of him are riddled with 30 to 40 bullet holes.

He knows how his neighborhood got this way, and how easy it is for young men to get sucked into the cycle of violence. Quentin started carrying a gun to protect himself and his family after he and his friends were shot at while playing basketball.

Quentin hit rock bottom when he woke up in an eight-by-ten jail cell in 2014, facing a weapons charge. He remembers leaving behind his daughter, Zariyah, who was only three years old.

"That's what hurt me the most," Quentin says. "I knew that there was a little girl that needed my help, that needed my time."

Quentin uses that experience to propel him to build a better future for his daughter and to lift his community out of violence and poverty.

His contribution is easily seen by driving down Honore Street in Englewood.

The house on the corner of 64th Street turns heads, with its colorful fence decorated with art and a beautiful garden. They call it the "Peace House," and it's the home of the non-profit organization "I Grow Chicago." Quentin is the co-executive director and the yoga instructor.

It is a place with summer and after-school programs for children. Parents can also get school supplies, toiletries and clothing for their families when their budgets are tight.

"If there was a Peace House on every block in Englewood, you wouldn't see the violence you normally hear about," Quentin says. "The more and more we bring in resources, the more and more that you will see the crime deteriorate."

Part of the success is due to how the Peace House was built -- literally. Robbin Carroll, who isn't from the neighborhood, bought the dilapidated home with its overgrown yard in 2013. Shortly after the purchase, she founded I Grow Chicago.

She hired young men -- some covered in tattoos, others with long rap sheets -- to rebuild it and to plant the garden. Her strategy was to help people in the neighborhood help themselves.

But police officers warned her she was taking a huge risk.

"The man you are doing this with is a cold-blooded killer," Robbin remembers an officer telling her one day while she was gardening.

Robbin didn't flinch. This was not about what the men had done in the past, but what the community could do together to move forward.

"If we each took a block and made the block thrive, we could completely end all this chaos," Robbin says.

Quentin and Robbin say the violence around the Peace House has dropped; they remain optimistic, but cautiously so.

In the middle of the night about eight months ago, Robbin says a bullet shattered the upstairs window and punctured the wall of the tutoring room. She refuses to patch up the hole left in the drywall.

"You are safe emotionally in our house; but I can never say that you can be safe here. So I refuse to putty over the bullet hole," Robbin says. "That always reminds us that it could be one of us in that spot."

CNN's Jake Carpenter, Leonel Mendez, and Kenneth Uzquiano contributed to this report.