Voices of Auschwitz

Elizabeth Ungar Lefkovits

"Eighty-seven persons in (my) family died -- my grandparents, all my aunts and uncles."

Tomas Lefkovits, son of Elizabeth Ungar Lefkovits

Editor's note: The following contains mature language

Tomas Lefkovits: As a defense mechanism, when his mother first talked about her experiences he fell asleep.

Courtesy Lefko Group

As a young boy growing up in Venezuela, Tomas Lefkovits dreamt of capturing and torturing Nazis. He was only 7 when he began stalking a man he'd spotted at the local swimming pool in Maracaibo because he was sure he'd found one. After Adolf Eichmann, one of the architects of the Holocaust, was captured in Argentina and later hanged in Israel, a pre-teen Tomas devoured every article about the case that he could find.

Though Tomas, 65, describes his childhood as happy and says his home was full of love and laughter, he also speaks of a profound sadness that hung in the air.

It would weigh on the family especially during Jewish holidays, when all the relatives he never knew – grandparents, uncles, aunts and cousins – were most noticeably absent. It was also when, during memorial services in synagogue, he watched his mother wail – drowning in pain he couldn't understand.

He and his sisters knew not to ask questions about her time in Auschwitz. Their father, also a survivor – of slave labor in Hungary – taught them early. "She's suffered enough," he'd tell them. "Leave her alone."

WATCH ON CNNgo

See "Voices of Auschwitz," a one-hour documentary marking the 70th anniversary of the liberation of the Nazi concentration camp, at CNNgo.

The first time Tomas heard his mother say anything about her experiences, he was 30, married and had three sons of his own. He and his family were temporarily living with his parents in Maracaibo. His mother sat in another room in the house and began chronicling her memories into a tape recorder. Tomas couldn't make out the words she spoke, only the anguished cries he'd come to know years before.

She has since shared her story often and publicly. He's only attended one of her speaking engagements. It was last January, at the Breman Museum in Atlanta. His sons sat in the front, while he took a seat in the back. While Tomas knows speaking is cathartic for her, her memories stir up only anguish for him. He left the museum utterly exhausted.

It's not that he doesn't know or care about what's she's been through; he just doesn't need to keep revisiting the depths of her pain. When she first began opening up about her past, she'd talk to Tomas' late wife. He'd sit there, too, but says he built up a defense mechanism in which he'd fall asleep as soon as his mother began speaking. He's never seen a therapist about this; he's afraid of what he'd find out. Just thinking about the suffering she's endured, he chokes back tears.

A drawer in his home office holds all of her memories. He flips through an unread lengthy transcription of every word she recorded back in Maracaibo, typed up by his parents' secretary at the time, and runs his fingers along a long row of tapes he says he'll never play.

"I'm no masochist," he says.

Tomas is comfortable putting on tefillin, phylacteries worn during prayers, and goes to synagogue every week. He embraces the beauty and philosophy of Judaism. But he cannot believe in God.

He's been involved in a discussion group for children of survivors and has chaired Holocaust Remembrance Day events.

When people refer to the Jewish people as "chosen," he scoffs.

"Chosen for what? Because so far, I haven't seen any benefits," he says. "Anybody who wants to convert to Judaism, they're crazy. They're fools."

But he's firm in who he is. Like his father, whose survival story was about heroic strength, and a family friend who was a freedom fighter during the war, Tomas insists he wouldn't cower to anyone.

"If I was told, 'Convert or else you die,' I'd say, 'Well, then, kill me,' " he says.

And if there was ever another deportation of Jews, he wouldn't budge.

"If they said, 'Jew, get in the wagon,' I'd say 'Fuck you. You're going to have to throw me in there dead, feet first, because I ain't going.'

Renee Firestone

"As long as my mind keeps working and I can speak, I will tell this story."

Klara Firestone, daughter of Renee Firestone

Klara Firestone, right, with her mother: "We had to succeed in every way in the name of those who were lost."

Being named for a deceased relative is common in Jewish families. It's a way to "bring back the neshama, or soul, of someone departed," Klara Firestone explains.

But for her and so many children of survivors, the tradition felt more loaded. They were named for those killed by Nazis – in her case her mother's sister, who was shot after being experimented on by doctors in Auschwitz.

"We were replacing all those family members in a very real sense," Klara, 67, says. "We had to succeed in every way in the name of those who were lost."

An only child, she was born to two survivors who married in Czechoslovakia soon after the war. Her mother survived Auschwitz; her father survived a forced labor camp in Hungary and then time in the concentration camp Mauthausen. The family moved to the United States when Klara was 1. She was raised in Los Angeles, in a community of survivors and their children.

The families got together often and, inevitably, as people milled around tables laden with food, someone would say: "Do you remember when all we wanted was a piece of potato or a slice of bread?"

Together, the adults would groan or nod.

Through moments like this, she began to glean what her parents had experienced. They didn't spell it out; they were more concerned with her being "a nice, normal American kid."

Some aspects of her upbringing, though, were far from normal. Klara didn't have babysitters. Nor did many of the other survivors' children she knew. Their parents, she says, didn't want to let them out of their sight.

The importance of learning was impressed upon Klara and other kids at every turn. Her parents signed her up for "every lesson known to man," she says.

"You will have education," they'd say. "It's the one thing that can't be taken away from you."

She was 12 when the movie, "The Diary of Anne Frank," came out. Her mother took her to see it. At some point in the film it clicked for Klara; she suddenly understood what she'd been picking up through osmosis all her childhood. After the movie ended, she and her mother talked. She can't remember details of the conversation, only that she was full of questions.

There was a time when Klara wanted to be a pediatrician, but she jokes that she "forgot to go to medical school." Instead, she became a therapist who works with survivors and their children.

She founded a group to support children of survivors and, alongside her mother, serves on the board of the Los Angeles Museum of the Holocaust. She also helped establish and remains involved with a worldwide network for children and grandchildren of survivors.

Klara says a disproportionate number of children of survivors work as therapists, counselors, psychiatrists and psychologists. It seemed a natural progression.

"Our parents were traumatized, so they raised us in the face of that trauma," she says. And how they "internalized that trauma affected how they raised their own children."

Some were determined not to pass on horrors of the past and kept children in the dark. Others were too tormented to hold back details and left children haunted by nightmares.

"The nurturing style of survivors as parents certainly translated into who we are," Klara explains. "And in some cases it gave us our own parenting styles."

Martin Greenfield

"My father said: 'Honor us by living -- not by crying.'"

Jay Greenfield, son of Martin Greenfield

Jay Greenfield: He left dental school to work beside his father, who'd lost his entire family in the war.

Jay Greenfield was about 10 when his mother sat him down. It was time he knew his father's history, how he'd lost his entire family. They all perished in Auschwitz with the exception of Jay's grandfather, who died in Buchenwald one week before liberation. His father was not much older than Jay when all this happened.

Her words hit him hard. Jay could picture the horror of losing his parents and his brother, who got a similar talk from their mother when he was older. He imagined what it must have been like when troops marched in and changed everything. He grasped the significance of this legacy he carried, even if it would be 20 years before his father would talk directly to him about his experiences.

"He didn't bring it up, and we didn't bring it up, but we knew about it," says Jay, 56. "We understood that he came to America and started a new life and a new family – and we were it."

This reality forged a closeness and commitment to one another that stuck.

Two years into dental school, Jay walked away and never looked back. More important to him than becoming a dentist was the opportunity to spend time alongside his father.

He returned to Brooklyn to work with his dad, who'd purchased the clothing business that first hired him in America 30 years before. Not long after Jay ditched school, his younger brother, Tod, left show business – he worked in set and lighting design – to join them.

Today, the two brothers are co-owners of the family business. Jay's work includes design, merchandising and sales, while Tod, 54, handles matters like facilities, personnel and production. They worry about running the business and free up their father to focus on what he loves most: supervising the shop as clothing is made and interacting with and advising customers.

On Jay's bucket list is a return, with his own children, to where his father was born. They would start at the front door of his father's childhood home in the village of Pavlovo – then in Czechoslovakia, now in Ukraine.

And in the place that became home, every suit that leaves Martin Greenfield Clothiers in Brooklyn is tagged with his father's name. Jay likes to think that those who wear them help keep the name alive.

Anita Lasker-Wallfisch

"It seems a completely ridiculous thing to say in Auschwitz, I played the cello."

Maya Jacobs-Wallfisch, daughter of Anita Lasker-Wallfisch

Maya Jacobs-Wallfisch: She believes she "contained all the feelings and mess and horror" that her parents never dared address.

Life has never been easy for Maya Jacobs-Wallfisch. She says she first showed signs of trouble by age 2, later became addicted to drugs, was saved in rehab and, after several tries, decided marriage wasn't for her.

The 56-year-old psychoanalyst, though, has an explanation. She believes she "absorbed much of the unconscious trauma" that swirled around her family, that she "contained all the feelings and mess and horror" that no one in her home dared address.

"We were never really told what had happened in any cohesive or organized way," she says.

She knew she was Jewish, but didn't know what that meant. The family lived in west London, in a poor area that was mainly Irish and black, and they were "fiercely secular." They celebrated Christmas. Identifying with Jews, she believes, was viewed by her parents as unwise, unsafe.

She says she felt like she didn't belong anywhere and that she was brought up with "no tenderness at all."

Once, when she was about 11 or 12, she came across hidden photographs of corpses and people who looked like the walking dead. She thinks she spotted her mother among them. But she was hunting in the house for cigarettes when she found them, knew she wasn't supposed to be digging around and locked the alarming images in her troubled mind.

Around the same time, a child in the neighborhood asked Maya why her mother had a phone number on her arm. Maya went to the source to find out. Her mother simply told her she'd explain when she was older.

Maya only got the story just before everyone else did, when she and her brother were handed advance copies of their mother's memoir, published in 1996.

Her older brother, a cellist like their mother (their father was a concert pianist), emerged from their upbringing unscathed. He left home at 16, found his life partner at 18 and "flew off," she says.

"He's totally fine," she adds with a laugh. "Bastard."

In Maya's work, she trains other professionals to understand what she calls transgenerational trauma and helps patients grasp how this sort of trauma affects them.

She knows she must forgive, that her mother's experiences and scars were not of her choosing. And she doesn't doubt for a minute that her mother loves her.

Her mother's world had been about survival, blocking out feelings in order to live. "Everything else," Maya says, was "at best a luxury, at worst incomprehensible."

Demonstrative love, warmth, support – the emotional sustenance Maya craved – her mother didn't have in her to give, she says. It was not deliberate, of course.

It was a "consequence and a complete absence of knowing any better," Maya says. "She had to give up things in her life to not go crazy. But it also meant that she wasn't able to provide things to me that were essential."

Eva Mozes Kor

"That's not possible – burning people, that is crazy."

Alex Kor, son of Eva Mozes Kor

Alex Kor: Being the son of survivors is "an added bonus;" it’s taught him strength and perseverance.

Courtesy Johns Hopkins Bayview Medical Center

Alex Kor grew up straddling two worlds.

In Terra Haute, Indiana, he and his younger sister were the only Jews in their elementary school. He was in sixth grade when two boys cornered him in a locker room, whipped him with a towel and taunted him with the phrase "Jew boy." Soon after, his family found swastikas drawn on their home with soap, along with the phrase, "Go home dirty Jew." Though his father seemed to just take it, the incident nearly sent his mother over the edge.

In Israel, where the family spent each summer with relatives, all Alex knew were other Jews – all of the adults, like his parents, Holocaust survivors.

Alex, 53, doesn't remember first noticing the tattoo from Auschwitz on his mother's arm. It was nothing unusual to him. In fact, in his mind it was weird not to see them, which is why he once asked the mother of a childhood friend in Indiana why she didn't have numbers on her arm.

He was taught early, maybe at age 5, that bad things had happened in the world, but that he need not worry. He felt protected and loved, even though he didn't have an extended family nearby like his friends. The Army vet who liberated his father from outside Magdeburg, a subcamp of Buchenwald, lived around the corner. He was why the Kors landed in Terre Haute – and he and his wife were the grandparents Alex otherwise would have never had.

While living in Denver in his early 30s, Alex once strolled into a meeting for children of survivors. He went thinking of it as a social opportunity, but became horrified when nearly everyone there said they had attempted suicide. Granted, the bulk of those who attended were 20 years older than him. They were children of survivors who'd lost spouses and kids they'd nurtured before the war. Alex's parents never knew that particular pain. And Alex certainly couldn't relate to these other children.

In his mind, being the son of survivors has been positive, a legacy to embrace. He's on the board of a second generation group. He's traveled with his mother to Auschwitz "11 or 12 times," he says. "I've lost track."

What his parents went through has given him strength and perseverance. It's been "an added bonus," a tool he keeps in his back pocket.

It came in handy when, at 26, he was diagnosed with testicular cancer. At first, he thought he'd die.

"My mom said, 'No. No. Your dad's a survivor. I'm a survivor. You're going to be a survivor.'"

Learn more about the survivors and witnesses of the Holocaust at the Shoah Foundation.

70th anniversary of Auschwitz liberation

Wolf Blitzer's Auschwitz

His grandparents were killed at Auschwitz. His father grew up in the village and was taken to a dozen slave labor camps. But it wasn't until he finally visited the death camp that the truth hit home for CNN's lead political anchor.

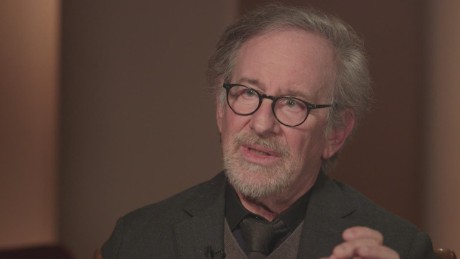

Steven Spielberg remembers

It started with "Schindler's List," when the Oscar-winning director filmed scenes outside the gates of Auschwitz. Seeing signs of hope amid the hopelessness, he would go on to start a project to record survivor's testimonies before it was too late.

The art of Auschwitz

Prisoners were forbidden to draw, paint, sculpt -- but they risked torture and death to express their creativity. Much of their work survived -- allowing us to see Auschwitz through their eyes.

The liberation of Auschwitz

Auschwitz was liberated on January 27, 1945. See scenes from the day the prisoners were freed.

Dancing for Dr. Mengele

As a teen in Auschwitz, Edith Eva Eger had to dance for the doctor known as the "angel of death."

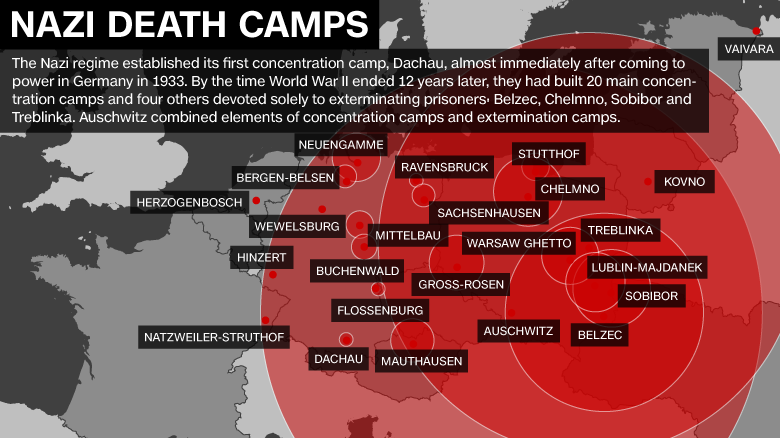

Interactive map: Nazi death camps

Horrific as it was, Auschwitz was only one camp complex in a system of more than 850 ghettos, concentration camps, forced-labor camps and extermination camps.