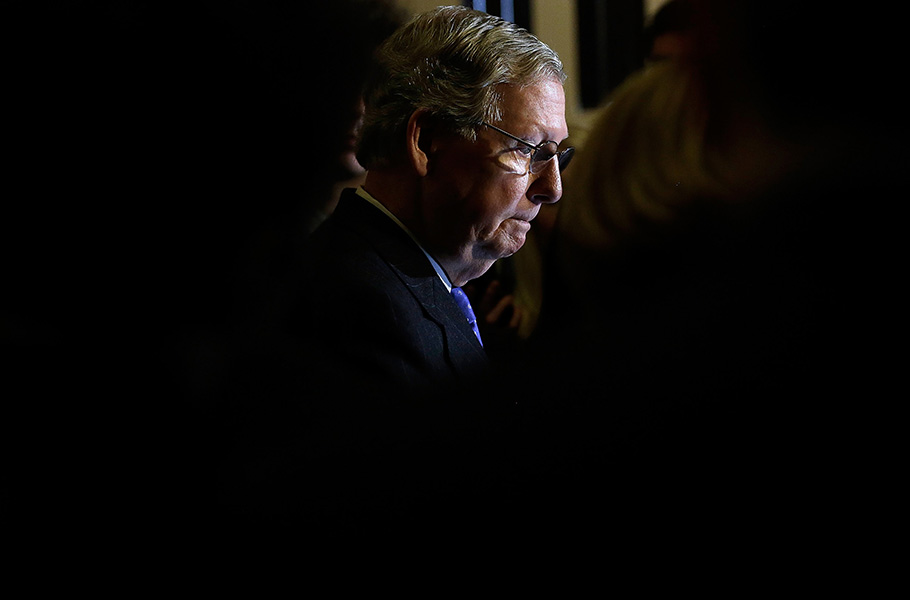

How Mitch McConnell crushed the tea party

By Peter Hamby, CNN National Political Reporter

Georgetown, Kentucky

Matt Bevin reaches into the breast pocket of his jacket and extracts a wrinkled, yellow piece of paper. "Fraud Alert," it reads, in alarming, official-seeming font. "Sensitive Materials Enclosed. Please Open Immediately."

A Republican he met received the notice in the mail a few weeks ago and showed it to Bevin, who now carries it with him wherever he goes.

Bevin, Mitch McConnell's tea party-backed Republican primary challenger in Kentucky, flattens it out on the table in the back of a community ballroom in Georgetown where he just addressed the Scott County Republican Party's Lincoln Day Dinner. The unfolded paper displays a litany of accusations against Bevin: He praised the Wall Street bailout in 2008. He doesn't pay his taxes. He padded his resume.

"This information is provided as a public service," the notice explains. It's an attack mailer from McConnell's re-election campaign, dressed up to look like an official government notice and sent to thousands of GOP primary voters across Kentucky.

Businessman Matt Bevin was the first serious primary challenger McConnell has drawn in four re-election campaigns, but his advisers say he wasn't prepared for the full-contact nature of a statewide campaign against a towering figure in Kentucky politics like McConnell. "The guy had no idea what he was getting into," one McConnell adviser said. (AP Photo/Timothy D. Easley)

"It's all made-up lies about me," Bevin complains, his voice rising as he vents about the negative tone of the primary contest. "It's unbelievable. It's crap. This is how he has run his entire race. He's attacking me for being a member of the tea party while threatening to crush these people and punch them in the nose. All of this is just absolute horse pucky."

Bevin’s indignation is a source of amusement to people who work for McConnell, who hear Bevin’s gripes and respond with a chuckle: What did he expect?

"The guy had no idea what he was getting into," one McConnell adviser says.

They can laugh because their private poll numbers look a lot like the public ones: McConnell coasted to a convincing win over Bevin on Tuesday, making Kentucky’s Republican Senate primary the greatest tea party challenge that never was. Of all the establishment GOP chieftains up for re-election in 2014, McConnell, the wily Senate minority leader who on any given day is either a proud obstructionist or a sly dealmaker, had the biggest tea party target on his back. But like other conservative primary challenges across the country this year, Bevin’s campaign sputtered, in no small part because of McConnell’s heavy hand back home.

The real fight, everyone here agrees, begins on Wednesday, when the still-unpopular McConnell begins his general election campaign against Democrat Alison Lundergan Grimes in what's shaping up to be the toughest re-election fight of his career. McConnell's unfavorable ratings are dangerously high and he is, to many, the face of Washington gridlock.

But McConnell's victory in the primary should not be overlooked, or simply dismissed as just a throwaway win over a hapless challenger. It's true that Bevin — like other tea party challengers across the country this election year — was imperfect, easily dismantled by McConnell's powerful and cold-blooded political machine.

Democrats see McConnell as vulnerable in November and have poured money into Alison Lundergan Grimes' campaign. She's gotten support from big-money outside groups and headline campaigners like Bill Clinton. Between spending by the campaigns and outside groups, the Kentucky race will likely be the most expensive ever run, with some estimates as high as $100 million. (AP Photo/The Gleaner, Darrin Phegley)

McConnell’s primary campaign can also be read, in some ways, as the climax of his long career in Kentucky Republican politics. He had never faced a real challenge from the right until this year, and he mined decades of battle-hardened experience and carefully-tended relationships inside the party --including an unusual one with his junior Senate colleague Rand Paul -- to win a primary that one Washington prognosticator billed as "the most important election of 2014."

After two straight election cycles in which Republicans fumbled winnable Senate races by nominating flawed conservative candidates, McConnell vowed early this year to beat back tea party-backed candidates and their supporters wherever they surfaced.

"I think we are going to crush them everywhere," he said in March.

The test that mattered most would take place in his own backyard.

The seeds of McConnell's win were planted four years ago, on a sunny Saturday at Kentucky Republican Party headquarters in Frankfort. Four days earlier, Rand Paul, a Bowling Green eye surgeon and the son of libertarian icon Ron Paul, had capped off his stunning ascent from relative obscurity to become his party's standard-bearer in the 2010 Senate race.

McConnell had picked another horse. After strong-arming the irascible Sen. Jim Bunning into retirement, McConnell enticed a protege, Secretary of State Trey Grayson, to run for the seat. He entered the race as the Republican frontrunner.

But like other grassroots-backed conservatives that year, Paul began to catch fire in late 2009 with a libertarian-tinged message of limited government. The race soon became the classic parable of the 2010 midterms. There were few differences on policy, but never mind: It was a clash that pitted the Republican Party's blazer-and-slacks wearing establishment, embodied by Grayson, against Paul, the tea party outsider.

After Paul cruised to a 23-point win in the primary, hurt feelings swelled. Polling revealed that some 40% of Republicans refused to support Paul in the fall against the Democratic nominee, Jack Conway.

Enter McConnell, the man Republicans in Kentucky often refer to as "The Godfather."

It's a term that connotes both reverence and fear, and with good reason. Dating back to his first election as Jefferson County judge-executive in 1977, McConnell has proven himself a brilliant tactician. He almost single-handedly built the Kentucky Republican Party up from nothing, guiding it through ups-and-downs of six presidencies. He accumulated national power with each of his own Senate elections, the first in 1984, employing a ruthless pragmatism that rewarded allies and punished foes. But he never abandoned his obsession with politics back home, down to the most local of levels.

"I have always been amazed with Sen. McConnell's involvement in not just U.S. Senate or U.S. House races, but state Senate, state House races," said Kentucky GOP Chairman Steve Robertson, who began working for the party as an intern in 1994. "I can recall evenings where we've had consultants and state legislators on the phone at 10 p.m., 11 p.m. at night talking about strategy, talking about the down and dirty, about direct mail pieces and what they're going to say. And Sen. McConnell wants to be on the call."

Josh Holmes, McConnell's top political adviser, says the minority leader "knows more than his entire staff combined, in terms of not only the nuts and bolts, but also the messaging."

Paul's primary win set off alarm bells for McConnell, who quickly recognized the Republican power shift unfolding before him. McConnell — who just two years earlier ran a campaign ad touting $1 billion in earmarks he had secured for parks and conservation projects, an unthinkable boast in today's spendthrift Republican Party — saw his party's center of gravity tilting in a new conservative direction.

"In 2010, he sensed the world was changing and he reacted accordingly," Grayson says.

McConnell moved quickly to bring the fractured party together quickly after the primary. He organized a unity rally in Frankfort, inviting Paul to share a stage with Grayson and promising to team up against Democrats that November.

It was, at times, an uncomfortable scene.

Grayson spoke briefly. McConnell mentioned Paul's name only once. The stage was crowded with party brahmins like McConnell, former Republican National Chairman Mike Duncan and longtime GOP congressmen Ed Whitfield and Brett Guthrie. But the audience was packed with rowdy Paul backers, some of them decked out in tri-corn hats and waving Gadsden flags. The diminutive Paul stood off to the side with his wife Kelly, looking more blasé than triumphant.

"We are here today to send a clear and unmistakable message to every Republican in Kentucky that we are going to elect Dr. Rand Paul to the United States Senate," McConnell told the audience that day. "The first step today is to unify our side, and then begin the process of reaching out to the other side."

McConnell and Paul weren't quite fast friends. Despite their huge profiles both nationally and in Kentucky, both men are private and guarded around newcomers. But they quickly realized they needed each other. McConnell wanted to bring a potential rival into his tent. And Paul badly needed help.

Paul's campaign was still a fly-by-night grassroots operation, still making questionable post-primary decisions like agreeing to appear on MSNBC's Rachel Maddow show, a booking that turned disastrous when Maddow surgically picked apart Paul's support, or lack thereof, for the Civil Rights Act.

McConnell's team was quick to offer advice without stepping on toes, people in both camps say. "They had serious input in terms of what we did in terms of television ads, in terms of what our overall strategy was," a Paul aide said. McConnell's team dispatched a top strategist, Josh Holmes, to lend a hand in Bowling Green. The National Republican Senatorial Committee also sent in veteran consultant Trygve Olsen to help. McConnell himself opened fundraising doors for Paul, freeing up money from skeptical Kentucky Republicans.

With discipline instilled, Republicans eventually came around in November. Rand won the election by a tidy 11 points, thanks in part to late mistakes by Conway. Paul swiftly began laying groundwork for a future Republican presidential bid, boosting his national stature in the process.

In the Senate, the outspoken Paul and McConnell, the methodical Jedi of the upper chamber, would sometimes disagree on tactics. But McConnell arranged plum committee assignments for his younger colleague, including a spot on the Foreign Relations Committee beginning in 2013 -- a prestigious post for a freshman, particularly a Republican with an anti-interventionist bent. By the time the two Kentuckians were caught on a hot mic last October strategizing about the government shutdown, a rare glimpse into the private dealings of elected officials, the two seemed to have developed a genuine rapport and mutual respect.

"Rand is very creative politically, and he's always got new ideas and thinking about ways to look at things differently," says one Paul adviser. "I think Mitch benefits from that."

Says a top McConnell adviser: "It started at a staff level. In addition to the principals getting along, the staffs got along. That's not always the case with senators from the same state in the same party. They developed a personal relationship where they could bounce ideas of each other. It's like any other relationship that works. Everybody tries to say that it's a mutually beneficially, cold relationship. It's just not. I've worked for a number of folks. It's as warm and give-and-take as any relationship I've seen."

The combined muscle of the two senators — one is the most powerful Republican in the Senate, the other a legitimate frontrunner for the GOP presidential nomination — is something McConnell invokes as he campaigns in Kentucky, a poor state that has come to depend on powerful representation in Washington.

"Kentucky has a couple of senators with some real swat," McConnell says. "That hasn't always been the case with a state our size. It an asset to Kentucky to have to members of the Senate who are major players in American politics."

Sensing that small government conservatives aren't easily swayed by such arguments, McConnell took no chances as his re-election bid approached. In September 2012, he stunned the political class by tapping Jesse Benton, a top adviser to both Ron and Rand Paul, to manage his Senate re-election bid.

Bringing a grassroots-groomed outsider into his day-to-day political circle smacked of craven opportunism, a blatant attempt to neutralize his right flank. But the move was vintage McConnell: Throughout his career, he has cared first and foremost about winning, elite opinion be damned.

McConnell recruited campaign manager Jesse Benton because of his ties to former Rep. Ron Paul of Texas and his son, Sen. Rand Paul of Kentucky. Benton saw the move as beneficial to Rand Paul's 2016 presidential ambitions and was secretly recorded saying he was "holding his nose" until then. The two later joked about Benton's remarks but sources say McConnell was hurt by them. (Team Mitch)

Benton himself seemed to think the hiring was transactional — telling a colleague that it would help Rand score points with the party establishment in advance of a presidential campaign. "Between you and me, I'm sort of holding my nose for two years," Benton told a former Ron Paul staffer, who recorded the call and released it last summer. "What we're doing here is gonna be a big benefit to Rand in '16."

The conversation was an embarrassment to McConnell when it was made public. McConnell himself was genuinely hurt by the comments, several GOP sources said. But Benton and McConnell made light of the fiasco, releasing a light-hearted but staged photo of Benton holding his nose while McConnell smiles.

As discordant as it seemed, hiring Benton was a no-brainer for McConnell, according to Grayson.

"Jesse is very talented," Grayson says. "Jesse knew the Rand network and that was valuable. And a narrative was avoided. What if there was a Rand Paul-backed tea party candidate?"

Paul ensured that wouldn't happen last year when he formally endorsed McConnell, a move that didn't seem like much of a surprise in the wake of Benton's hiring. The March 2013 endorsement would not be enough to prevent a challenger from entering the race — Bevin, a wealthy Louisville business man, entered the primary last summer — but it denied crucial oxygen to a noisy and still-restive slice of the conservative base.

"With Rand's endorsement there was never really a moment where you thought McConnell was in jeopardy of losing this primary," says one Paul adviser. "He was the glue that held it all together. There wasn't really a big crack in McConnell's armor."

National conservative groups like the Senate Conservatives Fund, FreedomWorks and the Madison Project were endorsing McConnell's primary challenger throughout last fall and winter, but with Paul in McConnell's corner, their arguments lacked punch.

"The foundation of the Bevin, SCF and FreedomWorks entire pitch was the Mitch is somehow a liberal who allies himself with President Obama," Benton said. "Reality already made that a tough sell, and with Rand Paul supporting us calling Mitch a good conservative, it made them all look rather silly."

Rand Paul has been called a turncoat by some conservatives because of his endorsement of McConnell. He's hoping McConnell returns the favor if he runs for president in two years. (Brendan Smialowski/AFP/Getty Images)

Still, the public dance between Paul and McConnell has at times been awkward. Paul has risked antagonizing the grassroots forces that supported him in 2010 by lending his support to the ultimate avatar of the Washington establishment.

Some conservatives in Kentucky already consider him a turncoat. John Kemper, one of the state's most outspoken conservative activists, says Paul's support for McConnell is emblematic of his gradual drift away from the conservative base.

"It won't be forgotten by Kentucky tea party folks," says Kemper, who now works for Bevin. "It's been more a detriment to Rand than a help for Mitch. It undermines his relationship with tea party folks in this state, folks who worked diligently to get him elected in 2010. They'll be unwilling to do the same thing for him in 2016."

Bevin is equally critical of Paul.

"I feel bad that he's made a bed for himself and it's becoming soiled," he says. "Here's what's sad. In order to win at another level, you need to get not only the people who got you to the dance, but everyone like them everywhere else, people like them all across the country. If it turns out your own base has been lost to you, you think that doesn't get around? Start to look at the comments sections on national blogs. They are increasing negative. It's brutal. It undermines the very conduit he had, which was this disconnected, disenfranchised, disenchanted group of non-establishment folks who want to take their party back. They're the people who are like, ‘That guy's a sellout.' And it's a bummer. He threw them away. But I do like Rand, I do."

Rand has complimented McConnell repeatedly in public, but he's also stumbled over questions about their relationship. At an April town hall in Edmonton, a constituent asked him why he endorsed McConnell. Paul said he would speak to her in private. He was asked the same question by radio host Glenn Beck during a trip to Texas in February. Paul tried to evade the answer, saying he was in town to endorse a local candidate. After Beck laughed, Paul responded: "Uh, because he asked me. He asked me when there was nobody else in the race. And I said yes."

If Paul isn't gushing about his endorsement at every turn, McConnell aides seem not to mind. It's better than having him on the other side of the trench lobbing grenades. At the end of the day, Paul is on Team Mitch.

"He is an extraordinary political talent," McConnell says of Paul. "The way he has burst onto the national scene, I initially think the attention was just because his dad had run for president. But now it's clear that he is a very credible national figure. I am proud of what he has done."

There are anxieties among some in Paul-world that McConnell might not return the political favor next year, when Paul embarks on his expected run for the Republican presidential nomination and will need a run-blocker in Washington to help fend off potential attacks from the party establishment. A McConnell adviser dismissed concerns about their relationship.

"There are a lot of people who question their sincerity, which I think is unfortunate," the adviser says. "Clearly at this stage neither one of them need each other. They both benefit really from each other's friendship."

Steve Robertson, the Kentucky GOP Chairman, echoes the sentiment.

"I'm sure that Senator McConnell would much rather pick up the phone and call from someone in the White House who is from his own state," he says.

McConnell's extended courtship of Paul has proven fruitful — but it wasn't enough to clear the Republican field.

In early 2013, Bevin, a Louisville investor originally from New Hampshire, was attending tea party meetings and having conversations with local activists about challenging the Senator from the right. McConnell's team picked up on the buzz and began assembling what would become a nearly 500-page opposition research dossier on Bevin.

They wasted little time putting it into effect. On the very week Bevin announced his campaign, the McConnell campaign unleashed a punishing television ad blasting the upstart challenger for taking state "bailout" funds to help repair a Connecticut-based factory he owned. The attack was designed to undercut one of Bevin's central attacks on McConnell — that he exploded the national debt, in part, by supporting the Troubled Asset Relief Program, or TARP, after the 2008 financial crisis (McConnell called the TARP vote "one of the finest moments in the history of the Senate"). In television commercials, robocalls, web ads and direct mail pieces, the McConnell forces dubbed him "Bailout Bevin" — and later revealed to reporters that Bevin himself praised TARP in a letter to shareholders in his mutual fund.

The decision to launch an early negative advertising blitz — which never relented — was a surprising move for a powerful incumbent against a little-known challenger, but McConnell has left little to chance, raising $21 million this cycle and spending more than half of it fighting a two-front war against Bevin in the primary and Grimes in the general. "Bailout Bevin" stuck, and the Republican was never able to get off the ground. The McConnell campaign had barely emptied the chamber.

"Literally 2/3 of the hits on Bevin are in the research book and will stay in the book," said one McConnell adviser. "They just weren't necessary, because he became defined."

McConnell had support on the airwaves from friendly interest groups and political organizations, including more than $1 million in television ads from the Chamber of Commerce and almost $2 million from a Super PAC called Kentuckians for Strong Leadership, which provided air cover to McConnell, running attack ads against Grimes while McConnell was occupied with the primary.

The challenger struggled to gain traction against the McConnell onslaught. Bevin has raised almost $4 million for his race, but that total includes nearly $1 million he has loaned himself. He's spent at least $3.3 million on the race — more than any tea party challenger since the inception of the tea party movement including Richard Mourdock, who spent $2 million in his successful primary fight against Indiana Sen. Dick Lugar in 2012.

But that sum did not appear to be enough to assuage friendly outside forces: The Senate Conservatives Fund stopped running pro-Bevin TV ads earlier this month. And notably, big-name conservatives like Texas Sen. Ted Cruz and Alaska Gov. Sarah Palin stayed out of the race.

Bevin's knack for self-inflicted wounds didn't help. He was caught on camera attending a pro-cockfighting rally in April — a blunder considered by many here to be the fitting final stumble of a ham-fisted campaign.

Bevin speaks to diners at the Village Restaurant in Liberty in April. By then, his stumbling campaign was no longer a threat and help from outside groups trickled to a stop, better spent on other campaigns that had a chance. (Tom Williams/CQ Roll Call)

Bevin's frustration with the take-no-prisoners attitude of the McConnell campaign strikes political observers on the ground as naive. "If McConnell has one unchangeable reputation in Kentucky, it's for being a scorched-earth campaigner," said Sam Youngman, the political writer for the Lexington Herald-Leader. "It's like going to NFL and complaining that they hit too hard."

It wasn't tactics alone that saved McConnell. The power of incumbency and his deep relationships in Republican politics made him almost impossible to topple. At a recent campaign stop in the southern Kentucky hamlet of Burkesville, McConnell, accompanied by his wife, Elaine Chao, worked a Cumberland County barbecue picnic like it was a family reunion. The county sheriff candidate, the county judge, a former state Senator, assorted civilians: They had all met McConnell personally in the past.

Clarence Rush, an Army veteran at the picnic with his family, was focused on a styrofoam plate full of ribs when McConnell strolled by and patted him on the back. Rush turned and looked up at the man behind him in pleated khakis. "I know who you are!," he shouted. "I know who you are!"

A few moments passed, and McConnell found himself chatting near a barbecue smoker with John Phelps, the Cumberland County Judge. Phelps later said he would be voting for the Senator in the primary.

"Our country has gone too far to the left, and he has stood up to Obama," he said. "McConnell is a real conservative. He stands for what America stands for. Look, Bevin is a good guy. He's going to pull some votes. But I think in the back of everybody's mind, we are prepping for November. Grimes is a major contender. The tea party, they have got some great ideas, but some of the time they get a little bit too far to the right. McConnell is going to be our best choice."

McConnell's stop in Burkesville, friendly GOP territory, felt like a victory lap. The Republican Party he had cultivated for decades had mutated into something slightly different, but here, it was once again firmly in his grasp.

The slightest hint of grin appeared on his face when asked for a status update on his promise to crush the tea party. But beyond that, he betrayed little emotion.

"I thought that this cycle it was important for us to make sure that in the real election, which is in November, we had people who could actually win," McConnell said. "Winners make policy. Losers go home."

CNN POLITICS

Key races to watch in 2014

Democrats have held the majority in the Senate for almost eight years, but as Election Day 2014 approaches Republicans are confident that math and history are on their side.

2014: What's at stake

With the entire House of Representatives and more than a third of the Senate up for election in November, there's a lot at stake in these midterms.