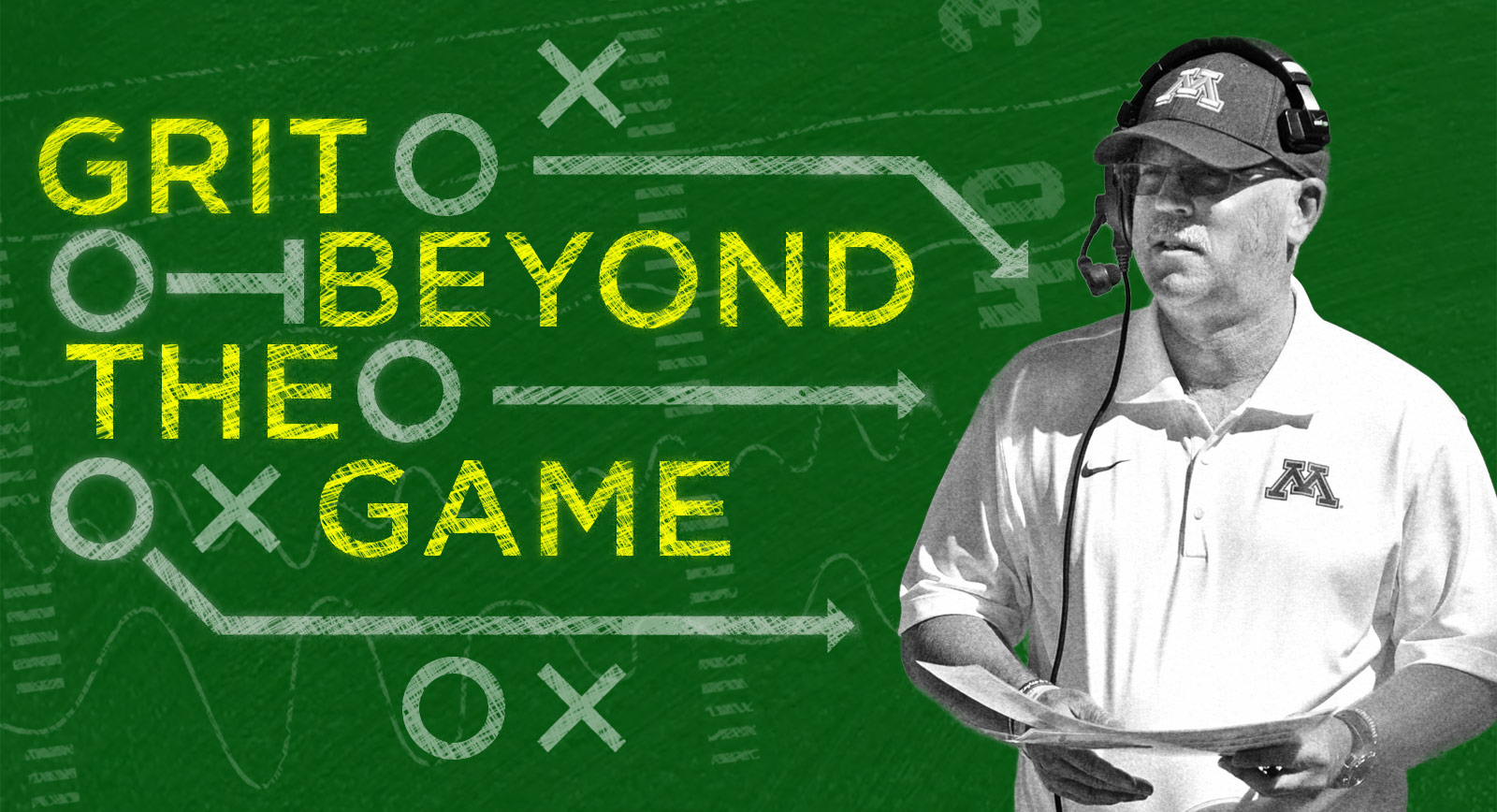

It's not all about winning for Minnesota football coach Jerry Kill. But his courage off the field has inspired his players, his fans and children with epilepsy — including mine.

By Wayne Drash, CNN

University of Minnesota head football coach Jerry Kill fields question after question. Reporters want to know less about the quality of his football team and more about his health.

Specifically, his seizures. The ones that left stadiums silent when he fell to the turf.

What's it like to step onto a field knowing you have epilepsy?

How long has it been since your last seizure?

Will you return to the sidelines or coach from the press box?

It's the second day of the Big Ten media blitz, and Coach Kill sits at a table at the Hilton Chicago for two hours. One by one, the reporters approach him. Kill jokes with his PR guy how he wishes he could sit them down, answer their questions all at once and be done.

During a break, the coach checks his email. A father writes saying he lost his daughter to a seizure. Keep fighting for us, the dad says. It's the third time in less than a month that a family has written to tell him a loved one has died from epilepsy.

Those messages really sink in, a reminder that his work extends far beyond the football field.

The author and his son mug for the camera during their visit to the Cleveland Clinic, where Billy was evaluated for brain surgery.

Courtesy Wayne Drash

I, too, have questions for Kill, but they're more personal. Epilepsy affects my family in every way. I know the fear of the father who wrote that note, but I hope to never know his pain. There are days when I grow angry and frustrated because nothing seems to help my son.

I want to ask the coach how he handles his seizures, what advice he has for families like mine. I especially want to know what compels this man to be so open about his epilepsy in a game overflowing with machismo when so many ordinary people hide from the disorder.

Kill, 53, wasn't always outspoken. He was thrust into action when scorn, hatred and ignorance were hurled his way. The accidental ambassador for epilepsy.

Freak. Unworthy coach. Someone who should be fired, as one local columnist wrote, because Golden Gopher fans don't pay money to be "rewarded with the sight of a middle-aged man writhing on the ground."

He's heard it all. He's found motivation, not in his own battle, but from children with epilepsy who flock to him. It's for them that he pushes back. "When you make fun of me," he says, "you're mocking my people!"

And my family.

Later in the evening, as the coach winds down in Chicago, my 10-year-old son, Billy, steps onto our front porch in Atlanta to take our dog for a walk. A fear flashes over his face, and he falls to his knees. He twists to the right. His right arm stiffens; his fist clenches; his eyelids flutter.

He crumples onto the wood planks. His breathing jerks along with his arms and legs. After about a minute, Billy takes a deep, long breath. The sign that he's OK.

It's his third grand mal seizure of the day. Sometimes, he'll look up like a boxer down for the count and mutter, "I hate seizures" or "Seizures suck." Other times, he cries.

This time, he's too out of it to say or do anything. I scoop him up and carry him to bed.

Distraught and winded, I lie down, too. When he seizes up, a part of my soul goes with him. More than 500 times, my soul has been chipped away.

Minnesota football coach Jerry Kill answered reporters' questions about his epilepsy at a Big Ten media day in Chicago this summer.

M. Spencer Green/AP

Coach Kill's first seizure was in bed in 2000; the next one, in 2005, saved his life. He was coaching at Southern Illinois University when he seized up during a game. He was rushed to the hospital and stabilized.

While there, his wife, Rebecca, told doctors he complained of extreme back pain. They discovered he had stage 4 kidney cancer. He underwent surgery at the end of the season and has been cancer-free for nearly nine years.

"If he had not had the seizure," Rebecca says, "I just don't feel like we'd have caught the cancer in time."

Although the cancer was gone, the seizures continued. Kill would go six months, sometimes a year, without one, thanks in part to the anti-seizure medication Keppra. Other times, the seizures would come more frequently.

Plenty of famous people have had epilepsy. Socrates, Julius Caesar and Napoleon Bonaparte were said to be epileptic, as was Harriet Tubman of the Underground Railroad.

Music stars Prince and Susan Boyle had epilepsy as children, as did NFL star twins Ronde and Tiki Barber. Rapper Lil Wayne began speaking about his epilepsy last year after seizures forced him to spend several days in an intensive care unit. Even professional race car driver Kenny Matthews has epilepsy.

More than 3 million Americans, including 450,000 children, suffer from epilepsy, defined by the Epilepsy Foundation as a disorder in which a person has two or more seizures "not caused by some known and reversible medical condition like alcohol withdrawal or extremely low blood sugar."

About 50,000 people with epilepsy — 1 in 60 — die from a seizure or seizure-related accident each year. Death can come from drowning, choking and suffocation during sleep. (A common misperception is that epileptics can choke on their tongues; they can't.)

Most people with epilepsy handle it privately, a revolving door of brain scans, doctor's visits and medication. Anything to get the seizures under control. Medication helps about two-thirds of those suffering. Brain surgery has about a 50-50 chance of success.

Yet most people with epilepsy are highly functional. It's just that their brain cells sometimes fire uncontrollably at high rates, creating "electrical storms" that cause their bodies to seize up.

"People assume that those with epilepsy need to be in a wheelchair or are devastated neurologically. That is not the face of epilepsy," says Dr. Anup Patel, a pediatric epilepsy specialist at Nationwide Children's Hospital in Columbus, Ohio.

"We must recognize the vast majority of people with epilepsy can and will live normal lives."

What makes Coach Kill so refreshing, Patel says, is that not enough people with epilepsy — especially those at the top of their professions — speak up about it.

Many adults with epilepsy fear losing their jobs. Children with the disorder fear losing their friends. They all fear being ridiculed.

That's what drove Kill to advocacy. After experiencing a seizure at the end of a game in 2012, he received an anonymous email saying, "We've got a freak coaching the Minnesota Gophers."

If he received such hate, he wondered, what was it like for a kid on the playground or regular folks hard at work?

On his next weekly radio show, Kill spoke up.

Kill had suffered sideline emergencies before, including this one in 2011, but it was a midgame seizure last fall that triggered a media firestorm.

Mark Vancleave/The Minnesota Daily/AP

"I'm not a freak, and neither are they. We're normal people," he told listeners. "And I'm going to work my tail end off for the people that have the same situation I have."

Last season, the ridicule didn't come from an anonymous emailer. It was splashed across the pages of the Minneapolis Star-Tribune. Kill had suffered a seizure during the fourth game of the season. He was taken off the field and sent to a hospital. The seizure, wrote columnist Jim Souhan, made the football program and the university "the subject of pity and ridicule."

Never mind the Gophers won the game. Never mind the team was 4-0. Enough was enough, Souhan wrote.

Yet a strange thing happened. If Souhan hoped to see Kill go, the column had just the opposite effect.

Minnesotans rallied around the coach, saying he stood for tough Midwestern roots. Fans wore "Jerrysota" T-shirts to games. People in the epilepsy community across the nation flooded Souhan's inbox and pinged him on Twitter. (He apologized in a follow-up column). A hashtag was spawned: #RiseAboveSeizures

At the coach's house, Rebecca Kill prayed. Long ago, she learned that reading the sports pages or listening to talk radio did little to calm the nerves of a coach's wife.

But this time, she was curious to see what was being said. Kill was home from the hospital, and things seemed better. Rebecca logged onto the computer. The words stung.

As she scrolled through the column, she says, her husband had another seizure. When he came to, she decided not to tell him about what was written. It was too hurtful and would be too much of a distraction.

The biggest test would come two weeks later — when she worried whether she'd lose her husband of 30 years.

For my 10-year-old, having an uncontrolled seizure can ruin his day. As his father, I just want him to have an ordinary shot in life. Most especially, I hope he won't have a seizure in front of his friends.

When my son seized in school last year, one classmate had an anxiety attack. On the playground, kids created a game called "Billy Touch." If you got tagged, you suffered from seizures. Teachers put an immediate end to it.

As friends posted happy photographs of the first day of school on Facebook in August, I couldn't bring myself to do it. In our house, the school year brings dread. "On the first day of school, I just want the boy to go a day without a seizure," I wrote.

It's been like that for the past three years, when his seizures began innocently enough. He zoned out for about 15 seconds, shrugged and repeated, "I don't know." He was standing at the front door, answering a question that was never asked. Since then, nothing has worked for longer than a few months. And the seizures have intensified.

At one point, Billy was on 15 pills a day at a cost of over $800 a month after insurance; we wondered if we'd have to get a second mortgage. Side effects from anti-seizure medications ranged from headaches, hostility and dizziness to mental slowness, problems with speech and potentially fatal skin rashes.

His meds often left him walking around like a zombie. At times, I couldn't recognize my own son — and he still had seizures. We've taken several vacations in recent years: a train trip to New Orleans, a swamp boat outing in Florida, a kayak adventure in Connecticut. He doesn't remember any of those trips because seizures along the way wiped his memory.

In late 2011, the author took his son, Billy, for surgical evaluation at the Cleveland Clinic, where he got a surprise visit from members of the Cleveland Cavaliers.

Chuck Crow/The Plain Dealer/Landov

In hopes of a breakthrough, I took Billy to be evaluated for brain surgery at the Cleveland Clinic. It was December 2011, and though I didn't know it at the time, Coach Kill had just finished his first season at Minnesota.

Billy and I spent five days round-the-clock in a hospital room under constant observation. More than 40 wires were hooked up to his head. Cleveland Cavaliers basketball star Kyrie Irving visited the room, as did Santa Claus. These kind acts made the week a bit more bearable.

At his lowest point there, Billy had 15 seizures in 12 hours. But that wasn't enough to qualify for surgery, which requires that seizures start in one region of the brain. His were all over the map. As one doctor said, "You don't open up the brain for a fishing expedition."

Of all our trips, for whatever reason, Billy remembers Cleveland. He talks about the bond the two of us had and how he would like to go back — that we had a great time together. I remember it with less glee.

Seizures affect children differently than adults. Because a child's brain is still developing, a seizure can wipe out an entire day of learning. That can make a simple assignment a frustrating ordeal.

Yet children can outgrow their seizures as their brains get larger and make new pathways. That's less likely for adults because their pathways have been formed.

And seizures come in many forms.

There are scientific names for the seizures my son has, but our family calls them Spaceouts, Startles, Twisties and Real MF'ers. It's the Real MF'ers that hurt the most.

Twice in the past six months, I thought my son was dying in my arms as he passed out and struggled to breathe. Two other times, he remained conscious while his body seized: "Make ... it ... stop," he screamed between gasps for air. The first time that happened, his mom went to another room to avoid fainting.

Billy's seizures come in spurts. His mom tracks them all on a calendar — when they happen, what kind they are, what triggers them. He had one four-month period without a seizure, and that was while we were weaning him off one of his medications. Now a seizure-free spell lasts, at best, five days.

His knees are scabbed from constant falls, his legs bruised. Five times, he's tumbled down stairs. He's scared of the staircase at home and crawls up and down it on all fours. He wears kneepads at all times now and uses elevators wherever possible.

My son is the class clown, quick with a joke and a laugh. He's goofy, funny, outgoing and loveable. He adores firetrucks, police cars and big rigs. He's also the toughest kid I've ever met.

My son is far more than his epilepsy, but it affects his life in ways big and small.

He's had to give up his two favorite activities: swimming and biking. He wants to be able to drive someday. "Make my seizures go away," he said as he tossed a coin into a fountain this summer. He made the same request of Santa last year and while blowing out his most recent set of birthday candles.

His older sister has been forced to grow up faster than her 13 years, pulling her brother away from the stairs when he has a seizure and Mom and Dad aren't in the room.

While Billy attended his first day of school this August, I spoke by phone with Rebecca Kill. She talked of having fears similar to the one I posted on Facebook, of hoping her husband won't have a seizure, especially in public.

Before every game, she prays her husband won't seize up. But it's not just a game-day worry. It's an everyday thing. Kill hasn't had a seizure for nearly a year, she says, "but you never know."

When Kill's seizures grew worse, his wife of 30 years took charge. Rebecca Kill found an epilepsy specialist, who forced the coach to make lifestyle changes.

Carlos Gonzalez/Minneapolis Star Tribune/Zuma Press

My son made it through his first day of school without a seizure. He announced this joyfully when I got home from work, his arms raised, a smile spread across his face.

The second day didn't go so well. He had one at home just before school, another in art class when he got his feet tangled in a stool, a third in the school hallway when his mom went to bring him home early. As he's gotten bigger, Mom can no longer lift him. The school nurse lugged Billy to the car.

His fourth came later that night, at the top of the stairs. Luckily, I was right behind him.

I used to carry a piece of paper in my wallet that said: "Flip him on his side to clear airway; get under his head so it doesn't bang on the ground; call 911 if it lasts more than five minutes."

I don't need the paper any more. Instinct kicks in. I grabbed Billy and flipped him on his side. We were both awkwardly splayed across the floor, his head twitching on my chest. "Dad's here. Dad loves you," I said in a loop.

My cell phone rang in my pocket. I would later learn it was a 12-year-old boy with epilepsy calling from Blaine, Minnesota. Tyson Strand wanted me to know that Coach Kill helps children with epilepsy dream big: "A lot." At a camp this summer, the coach gave him the hat off his head. Tyson keeps it on a shelf in his room.

When Billy's seizure ended, I put him in bed and sat with him. He slept a bit and then awoke somewhat groggy.

"Why am I having seizures every day now?"

Me: "We're trying to figure that out."

"Do some people die from seizures?"

"Well, some people do, but let's not think about that. The important thing is that you're here now, and I'm with you. We're trying to find medicine that works."

"I can't help it when they come,"he says.

"I know that. Nobody can. Just like that coach."

"Does he try to stop seizures?"

"He tries, but he can't stop all of them. His medicine helps. He still coaches and leads his team and wins."

Coach Kill fell into a spin, the first of several dramatic seizures. He was at home on a Friday last October, preparing to catch a flight with his team to Ann Arbor. The Gophers were about to face the University of Michigan.

It had been almost two weeks since his in-game seizure and the media fallout that followed.

But this was completely different territory. His seizures wouldn't stop. First one, then a second, then another and another. Finally, in the late afternoon, he started to come back around.

"Can I still make the game?" he asked his wife.

"Yeah, you've still got time," Rebecca responded.

But the seizures picked up again. The team flew to Michigan without its coach.

Rebecca made arrangements to catch a 7 a.m. charter flight on Saturday. She'd done the math and figured out the latest time they could leave and still make kickoff.

But when morning came, the seizures didn't abate.

It was the first time seizures forced him to miss an entire game.

After a seizure last fall, a local columnist called for Kill to go. Fans responded by wearing "Jerrysota" T-shirts and rallying around the coach. The team finished with its best record in a decade and faced Syracuse at the Texas Bowl.

Trask Smith/Zuma Press

When Kill awoke late that afternoon, he looked up and saw his suit hanging in the exact spot from the day before. He didn't need anybody to explain.

"That's the lowest point, without a doubt," he recalls.

The coach wept. And the team got routed, 42-13. His defensive coordinator and longtime assistant, Tracy Claeys, stepped into the head coaching duties that day. He was upset with himself because he wanted to get the win for "Killer," as he calls his boss.

"None of us wants to disappoint him," Claeys says. "Just personally he's done so much for us, you hate to see him go through it."

Rebecca wasn't about to give up on her husband and his dream job leading a Division I program. They'd been through too much in their 30 years. The couple met when Rebecca was 17 and Jerry was 19. That day, Jerry announced in front of her parents — and her boyfriend: "I'm going to marry you one day."

They got hitched two years later. They lived in a trailer as her husband scratched out $250 a month as an assistant college coach in Pittsburg, Kansas, a blip of a town in the southeastern part of the state.

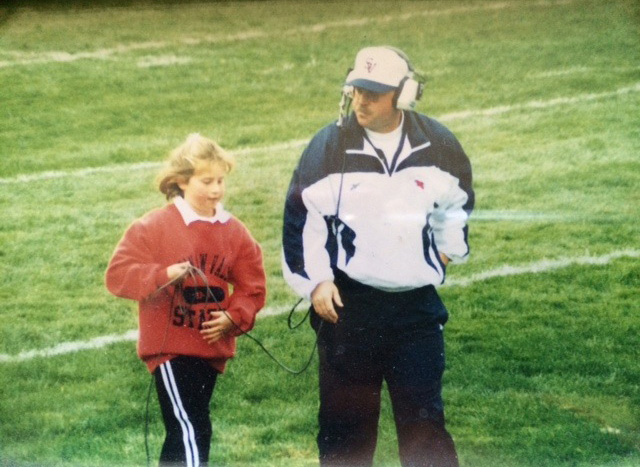

Football became intertwined in Rebecca's life and that of their two daughters, Krystal and Tasha. As little girls, the pair ran the clock during practices. During games, Krystal stood next to her dad — "the person I look up to most in life" — holding his headphone cord. At 7, she got tackled but maintained her grip on the cord. She dusted herself off, hid her tears from her father and hopped up: "Yeah, I'm good."

Football has long been part of the Kills' family life. As a child, Krystal would hold her dad's headphone cord during games. Today she keeps an eye on him and knows what to do if he has a seizure.

Courtesy Kill Family

The family lived the rolling stone life of so many coaches in the lower rungs. Dusty roads. Tiny stadiums. Endless nights. Stops included: Webb City High in Missouri, Pittsburg State in Kansas, Saginaw Valley State in Michigan, Southern Illinois University and Northern Illinois University.

Work hard. And do it the right way.

That's Kill's motto. It's not a fancy logo made for T-shirts but a simple philosophy that's gotten him far in life. He hit the coaching jackpot four years ago, tapped to coach the Golden Gophers, a perennial football punching bag in the Big Ten. The pay has gotten better too; his salary this season is $2.1 million.

The coach's specialty: turning around struggling programs.

He'd had seizures during games before, but in small markets where no one made a big deal out of them. He'd go to the hospital, get stabilized and immediately charge back to practice.

But last October when he missed the Michigan game, with his seizures growing more intense, more worrisome, he and his family faced their biggest challenge.

"Through all the years, I never thought that he was going to die from a seizure, and this time, I thought maybe he was," Rebecca says. "It was just scary."

Kill's father was once kicked by a cow that shattered his leg; he grit his teeth, never went to the doctor. The coach would need to draw from that same toughness, but unlike his father, he'd need the best doctor possible.

Tasha rushed home from college. Krystal was already home; she was living with her parents while teaching special needs teenagers at a high school.

Krystal wasn't afraid of her father dying. It was more a fear of him losing his dream. "We were scared he was just at that point where he couldn't do it anymore," she says, crying. "Football has been our whole life. Literally."

Now 26, Krystal started on the sidelines with her father at 6. Today, she still occupies a spot along the field with the team, one eye on Dad. She knows exactly what to do if he has a seizure. She no longer holds his headphone cord. If anything, she's a cord that helps bind the family.

"Epilepsy hasn't made us grow apart," she says. "It's made us grow together."

With the coach in desperate need of medical care, Rebecca took charge. She worked with the Epilepsy Foundation of Minnesota to find the best available specialist. They were referred to Dr. Brien Smith, an epileptologist in Grand Rapids, Michigan.

Rebecca and the coach flew out for about five days of observations. It was a bye week, so Kill didn't need to worry about missing another game. The coach wouldn't rush out of the hospital this time. He was forced to listen to the doctor and told to make lifestyle changes.

Kill begins every practice with a moment of silence to honor former linebacker Gary Tinsley, who died of an enlarged heart in 2012. His photo hangs on a locker room door with the message, "Gopher Nation, do GT proud."

David Joles/Minneapolis Star Tribune/Zuma Press

He had averaged two and a half hours of sleep a night for the past nine years, even in the offseason. He gulped down Diet Coke and coffee by the gallon. Always on the go, he rarely ate three meals a day.

All of that, combined with the stress of running a football program, finally caught up with him. "I'm a guy who is wired to go all the time," he says. "Sometimes, that's my worst enemy."

Claeys, his assistant, says Kill wants to win so much "for the people of Minnesota" that it pushed him to the limits.

"When we lose, he takes that personal, like he's letting down the president of the university and the entire state," Claeys says. "Eventually, it got to where it took a toll on his body."

With the team sitting at 4-2, Kill returned to coach the Gophers' next game, but this time from the press box rather than the sidelines. He'd coach from there for the remainder of the season.

His team didn't disappoint. They won four straight Big Ten games for the first time since 1973 and finished the year 8-5, their best season in a decade. And their coach went seizure-free.

Kill was named one of five regional coaches of the year by the American Football Coaches Association. He deflects the praise in his aw-shucks way: "It was a team award."

While Kill and his family sought treatment last October, my family did, too. We took a 1,400-mile road trip to Colorado.

We heard stories of epileptic children there taking a liquid form of medical marijuana made from a strain called Charlotte's Web. The oil brought their seizures in check; in some cases, they stopped.

We wanted to see this for ourselves, to hear their stories firsthand. We met with about two dozen families, colloquially known as medical marijuana refugees. Families just like us that had packed up everything and moved across the country to establish residency so their child could receive the medicine.

With Charlotte's Web, the psychoactive part of marijuana known as THC is reduced to less than 1%, while the nonpsychoactive portion known as CBD is boosted. Even calling it medical marijuana seems a bit of a misnomer.

A stoner getting his hands on Charlotte's Web would be about as excited as a 21-year-old shotgunning an O'Doul's nonalcoholic beer.

From these families and children, the stories were remarkable: Kids with 1,000-plus seizures a month were now having one or two. Most of those children suffered from a condition called Dravet Syndrome, a debilitating, intractable form of epilepsy that begins in infancy, different than my son's.

Still, the evidence was stunning.

We drove through neighborhoods and pondered tough questions: Do we move out here? What if we do and it doesn't work? What about our friends, family and neighbors who serve as our support network: Can we leave them?

Soon, dozens of legislatures — including Minnesota's — were passing laws to give epileptic children access to Charlotte's Web. We decided to stay put in Georgia and see how it played out.

Earlier this year, Georgia lawmakers debated whether to legalize Charlotte's Web. Though I didn't know if the CBD oil would work for my son, I took him to the hearings.

Working with his tutor and mother, Billy wrote a statement that he hoped to read to state lawmakers. Public comments weren't allowed when we were present, so we gave his letter to our local representative, Margaret Kaiser, and she read it on the House floor.

"I have seizures everywhere. I've had them walking across the street, at CVS, in the swimming pool and on my scooter," Billy wrote. "I've had them when I walk up the stairs, when I brush my teeth, and when I dance Xbox. At school, I've had them in the lunch line, in the bathroom and in my classes. ...

"We are learning about the different branches of government at my school. We learned that you make the laws in Georgia. I am writing this because I want you to make a law to help me with my seizures."

Although the state House and Senate passed separate bills, lawmakers failed to reach an agreement that would have legalized medical marijuana for epileptic patients.

At least one epileptic child in Georgia hoping for Charlotte's Web has since died. A mother in Georgia whose daughter has epilepsy wrote to us, saying if her daughter could speak, "This would be her letter, too."

My son may have a disability, but he stood up for a cause. How many 10-year-olds can say that?

Kim Skriba holds a photo of her 15-year-old son, Ryan Smith, as Janea Cox kisses her daughter Haleigh last spring at the Georgia Capitol, where lawmakers debated whether to legalize medical marijuana for epileptic patients.

David Goldman/AP

Coach Kill walks to the 50-yard line of the practice field, drops to a knee and takes off his baseball cap. His players and coaches fall in line.

Every Gopher practice begins with a moment of silence to honor former linebacker Gary Tinsley, who died of an enlarged heart in his campus apartment on April 6, 2012. A photo of Tinsley still hangs on the locker room door with this message: "Gopher Nation, do GT proud, continue his work."

It's another reminder that life is precious.

After a minute, the coach stands, blows his whistle three times and hollers: "Let's go to work."

Players scurry to various practice stations. Kill monitors it all, mostly as a quiet observer. He's got a bright red face and farmer's tan from coaching in the sun so much.

He is a plainspoken Midwesterner, as simple as Kemps vanilla ice cream. That don't-feel-sorry-for-me attitude comes across when he talks about his epilepsy.

"I've lived a blessed life. I've got a beautiful wife, beautiful kids. I've had a chance to coach football at all levels. I've been a part of great kids and great people. So I can't really say I've suffered or anything like that.

"I've hit a few rocks in the road, just like everybody, and you deal with the rocks in the road. That's all you can do."

He's known to be loyal to staff, players and friends. Got a child with epilepsy? He'll hand out his personal cell phone number. "Call anytime," he says.

The Minnesota coaching staff is among the most-tenured in college football: Six have been together for at least 13 years, dating back to their days at Southern Illinois University. Three assistants, including Claeys, have stuck together nearly 20 years, since they first met at Saginaw Valley State.

Back then, the assistant coaches got paid little. At one point at Southern Illinois, Kill sacrificed his own salary so his assistants could get raises — what amounted to roughly $16,000 apiece over two years. And he's continued with that generosity on the big stage.

"Every time, he's put up some money to make sure that the staff is taken care of," Claeys says. "When you get around a coach like that, it's more about the team. And he truly not only preaches it but lives it."

Claeys was with Kill in 2005 when his first on-field seizure struck. "The first time, it scares the hell out of you," he says.

Coaches and staff now know what to do. "Like anything," Claeys says, "the more knowledge you get and the better understanding you have, the better you deal with it."

The biggest lesson learned, he says, is "you don't judge people by it. It doesn't make someone any less of a person or less capable of doing their job."

The Gophers are now focused on the season at hand. Kill has stopped drinking sodas and cut back on coffee. He's made time for regular meals and started sleeping six hours a night. He's had sleep apnea for a while but hated the CPAP machine; now he's using it regularly.

He hadn't driven his car in two years and set a goal in the offseason to do so again. He now drives a Ford Explorer the three miles from his house to the university every day. He doesn't like driving beyond that in the city, but the new freedom serves as a reminder "how the simple things in life are pretty good."

He has been weaned off Keppra — widely known in the epileptic community for causing temper tantrums — and put on a new medication. He hasn't had a seizure since last October.

Rebecca and Claeys joke that Kill is also more relaxed, more chilled out. "It's like I got a new man," Rebecca says, laughing.

"He's still demanding as hell," Claeys says, "but he's not nearly on edge."

While he oversees practice this day, across town Rebecca and daughter Krystal join more than 1,500 people for a "Stroll With Epilepsy" in St. Paul. Four other fundraising walks are being held in other Minnesota cities.

Among those on hand is Miss Minnesota, Savannah Cole, who has made epilepsy awareness her platform because a close friend suffers from seizures. Also in attendance are Brett and Travis Boyum, a father-and-son tandem who both have epilepsy.

Travis is 16 and has had seizures since he was 4. His father began suffering from seizures six years ago at 40.

Travis plays football and lacrosse for his high school team. He says Kill's effect on children and teens with epilepsy is immeasurable. If someone starts to make fun of you, he says, "Then, you can be like: 'Coach Kill has it, too.'

Kill and defensive back Cedric Thompson raise the Little Brown Jug after the Gophers' 30-14 win over the Michigan Wolverines in September. The earthenware trophy is awarded to the winner in one of the country's oldest college football rivalries.

Leon Halip/Getty Images

"It's almost like he's a celebrity in our state. To me, it's like: He can achieve it, so why can't we?" Travis says. "If he can have a seizure in front of that many fans and appear to us that he doesn't have any problems doing that, it gives me a lot more confidence standing in front of a large group of people to say: 'I have epilepsy.' "

The Minnesota Twins asked Kill to toss out the first pitch at a baseball game this spring to raise epilepsy awareness. The coach deferred the honor to Travis.

I heard similar stories from Minnesota families with epileptic children who said Kill's genuine care for the kids is a nice break from an otherwise painful world. He's formed the Chasing Dreams fund to help with seizure-smart school initiatives across the state; the fund also pays for a summer camp for children with epilepsy.

Campers have a standing invitation to attend closed Gopher practices. On November 15, the Gophers will host Ohio State University and the third annual Epilepsy Awareness Game.

In the rough-and-tumble recruiting world, Claeys says, Big Ten teams have tried using the coach's epilepsy against him. Kill brings up his seizures to parents and prospects first.

Often, he's accompanied by Claeys, who stands at 6-3, 350 pounds. The defensive coordinator stares down, asks moms and dads: Do you want your kid to get a great education, play at a high level and get developed for the NFL?

"Well," he says, "there's nothing with coach's condition that gets in the way of providing any of those things."

If anything, it shows he's a fighter.

Kill's fourth season leading the Gophers is under way. Last month, the team traveled to Ann Arbor to play Michigan. This time, Kill made the trip.

The Gophers smashed the Wolverines, 30-14, improving to 4-1 on the season and winning on Michigan's home field for the first time since 2005. Minnesota faithful called it one of the biggest victories of the last 25 years.

When the buzzer sounded, Coach Kill and Rebecca hugged on the field, holding each other tight and cherishing the moment. Krystal was right there by her dad's side.

In front of a nationally televised audience, Kill thanked his wife for sticking by him and gave a special thanks to Dr. Smith in Grand Rapids for "saving my career." The win, he said, was most important for the long-suffering faithful of Gopher football.

"I guarantee you, the state of Minnesota and the people back there, they're rocking and rolling right now," he said.

Minnesota's goal is to win the Big Ten for the first time since 1960. The victory over Michigan shows that a conference title may not be too far-fetched. "Why not us?" Kill says.

In Atlanta, the Gophers have picked up a new fan. On Saturdays, Billy has started paying attention to that team from the upper Midwest. He recently held up a photo of Kill: "Does he really have seizures, Dad?"

On his 11th birthday, Billy donned a maroon-and-gold Gopher jersey. He said he wanted to be like the coach; he set a goal to go the day without a seizure.

He accomplished that feat — news he happily relayed to grandparents by phone.

A small but significant victory.

Follow CNN's Wayne Drash on Twitter or contact him by e-mail.

CNN Longform

What drives Danny Thompson?

Why would a 64-year-old blast across the Utah desert faster than a 747 at takeoff? For Danny Thompson, it’s all about proving something to his famous father — and himself.

'My son is mentally ill'

He is 14 and hears voices. He's been hospitalized more than 20 times. Stephanie Escamilla is tired of seeing the country focus on the mentally ill only when there's a national tragedy. So she and her son are telling their story.

The gift of Charles

He was a troubled 13-year-old when he finally found a home, with parents and siblings who embraced him. But Charles Daniel would live only two more years. It was time enough to change everything — and everyone.

24 hours in the world's busiest airport

With 95.5 million passengers and 930,000 takeoffs and landings, Atlanta’s airport is No. 1. CNN pulls back the curtain to expose a world unto itself — and countless untold stories.